At GitHub, we put developers first, and we work hard to provide a safe, open, and inclusive platform for code collaboration. This means we are committed to minimizing the disruption of software projects, protecting developer privacy, and being transparent with developers about content moderation and disclosure of user information. This kind of transparency is vital because of the potential impacts to people’s privacy, access to information, and ability to dispute decisions that affect their content. With that in mind, we’ve published transparency reports going back six years (2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, and 2014) to inform the developer community about GitHub’s content moderation and disclosure of user information.

A United Nations report on content moderation recommends that online platforms promote freedom of expression and access to information by (1) being transparent about content removal policies and (2) restricting content as narrowly as possible. At GitHub, we do both. Check out our contribution to the UN expert’s report for more details.

We promote transparency by:

- Developing our policies in public by open sourcing them so that our users can provide input and track changes

- Explaining our reasons for making policy decisions

- Notifying users when we need to restrict content, along with our reasons, whenever possible

- Allowing users to appeal removal of their content

- Publicly posting all Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and government takedown requests we process in a public repository in real time

We limit content removal, in line with lawful limitations, as much as possible by:

- Aligning our Acceptable Use Policies with restrictions on free expression, for example, on hate speech, under international human rights law

- Providing users an opportunity to remediate or remove specific content rather than blocking entire repositories, when we see that is possible

- Restricting access to content only in those jurisdictions where it is illegal (geoblocking), rather than removing it for all users worldwide

- Before removing content based on alleged circumvention of copyright controls (under Section 1201 of the US DMCA or similar laws in other countries), we carefully review both the legal and technical claims and give users the option to seek independent legal advice funded by GitHub.

In 2020, current events, including the global pandemic and an increased focus on racial inequality and social justice, influenced policy and behavior on GitHub. A few notable examples:

- We saw an uptick in reports of hate speech and discriminatory content on our platform, including in direct relation to movements such as Black Lives Matter, as well as the political climate in the US, and the renaming of the default branch of GitHub repositories.

- We shipped a new restriction on misinformation and disinformation in our Acceptable Use Policies in anticipation of the 2020 elections in the US and elsewhere, as well as the onset of COVID-19. This restriction better equips us to take action against false, inaccurate, or intentionally deceptive information on our platform that is likely to adversely affect the public interest (including health, safety, election integrity, and civic participation). In the rare cases where we do see a potential to take action, given the nature of content on our platform, we’d typically only need to ask for clarification, not remove content. While we applied this term in very few cases, we did contact repository owners in a few instances to request they add a disclaimer or otherwise clarify sources of information, for example, with respect to do-it-yourself respirators.

- Hacktoberfest, an event designed to encourage people to practice contributing to open source projects, was particularly notable this year due to a third-party video that led to a massive uptick in reports, especially spam and disrupting others’ experiences on GitHub, at the start of October.

Focus areas for this year’s reporting, including what’s new

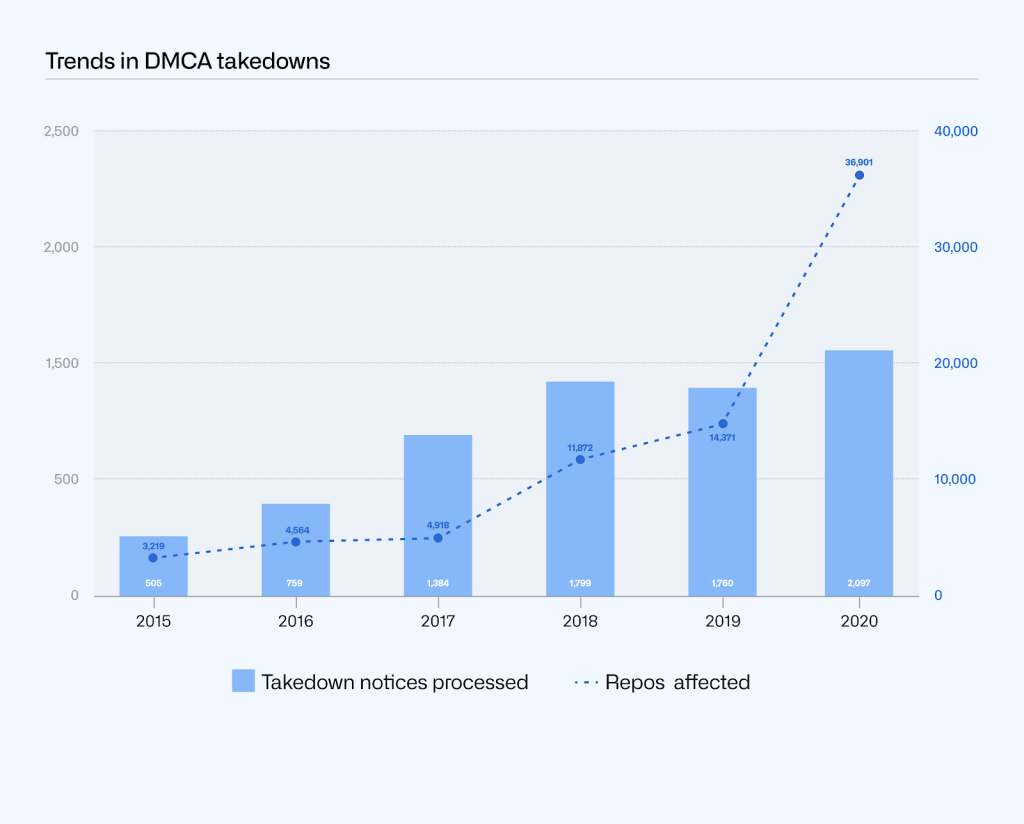

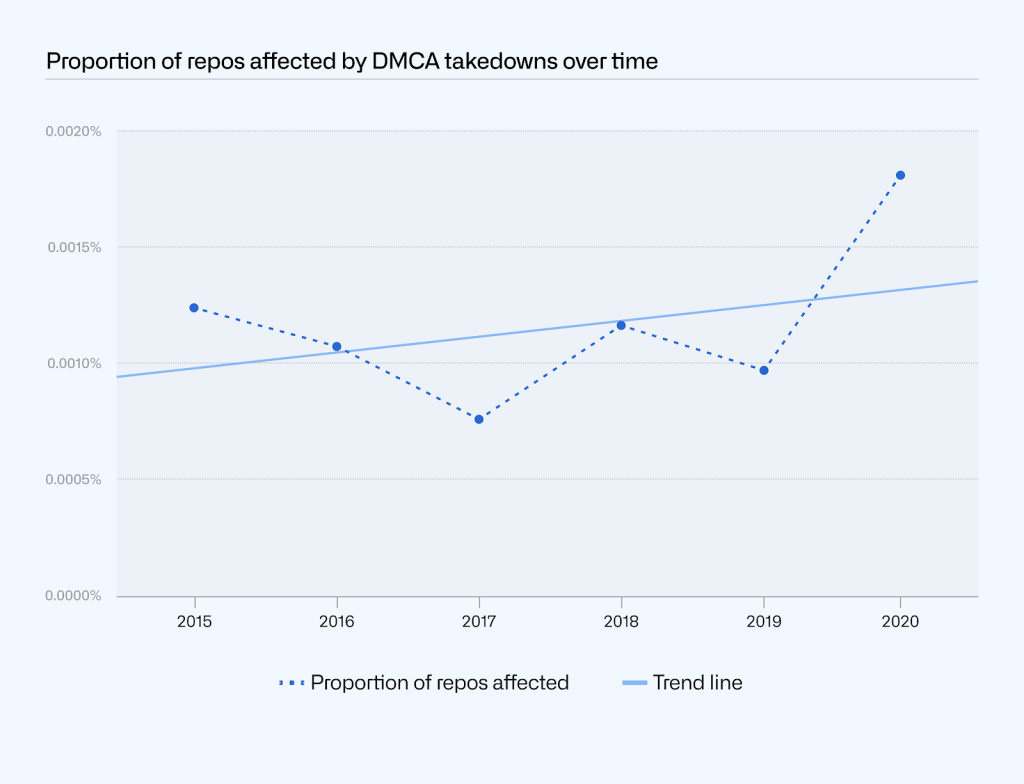

In this year’s numbers-based reporting, GitHub continued to focus on areas of strong interest from developers and the general public, such as requests we receive from governments—whether for information about our users or to take down content posted by our users—and copyright-related takedowns. Copyright-related takedowns (which we often refer to as DMCA takedowns) are particularly relevant to GitHub because so much of our users’ content is software code and can be eligible for copyright protection. That said, only a tiny fraction of content on GitHub is the subject of a DMCA notice (under two in ten thousand repositories). Appeals of content takedowns is another area of interest to both developers and the general public.

This year we’re increasing transparency by adding reporting in a number of new areas:

- DMCA takedowns based on alleged circumvention of a technical protection measure

- For legal requests for user information, breakdown by type for requests when we disclosed information (previously we reported on this only for requests received)

- Account and content reinstatement, including due to appeals, related to violations of our Acceptable Use Policies, which are part of our Terms of Service (while our DMCA numbers have always included appeals in the form of counter notices, this year’s reporting extends to other violations)

- Appeals of account restrictions due to trade sanctions laws. This is an entirely new category in 2020, for which we expect to see decline in 2021 after our January announcement of a new license to offer our services for developers in Iran, a major victory for global code collaboration.

Putting that all together, in this year’s Transparency Report, we’ll review 2020 stats for:

Continue reading for more details. If you’re unfamiliar with any of the GitHub terminology we use in this report, please refer to the GitHub Glossary.

GitHub’s Guidelines for Legal Requests of User Data explain how we handle legally authorized requests, including law enforcement requests, subpoenas, court orders, and search warrants, as well as national security letters and orders. We follow the law, and also require adherence to the highest legal standards for user requests for data.

Some kinds of legally authorized requests for user data, typically limited in scope, do not require review by a judge or a magistrate. For example, both subpoenas and national security letters are written orders to compel someone to produce documents or testify on a particular subject, and neither requires judicial review. National security letters are further limited in that they can only be used for matters of national security.

By contrast, search warrants and court orders both require judicial review. A national security order is a type of court order that can be put in place, for example, to produce information or authorize surveillance. National security orders are issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a specialized US court for national security matters.

As we note in our guidelines:

- We only release information to third parties when the appropriate legal requirements have been satisfied, or where we believe it’s necessary to comply with our legal requirements or to prevent an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to a person.

- We require a subpoena to disclose certain kinds of user information, like a name, an email address, or an IP address associated with an account, unless in very rare cases where we determine that disclosure (as limited as possible) is necessary to prevent an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to a person.

- We require a court order or search warrant for all other kinds of user information, like user access logs or the contents of a private repository.

- We notify all affected users about any requests for their account information, except where we are prohibited from doing so by law or court order.

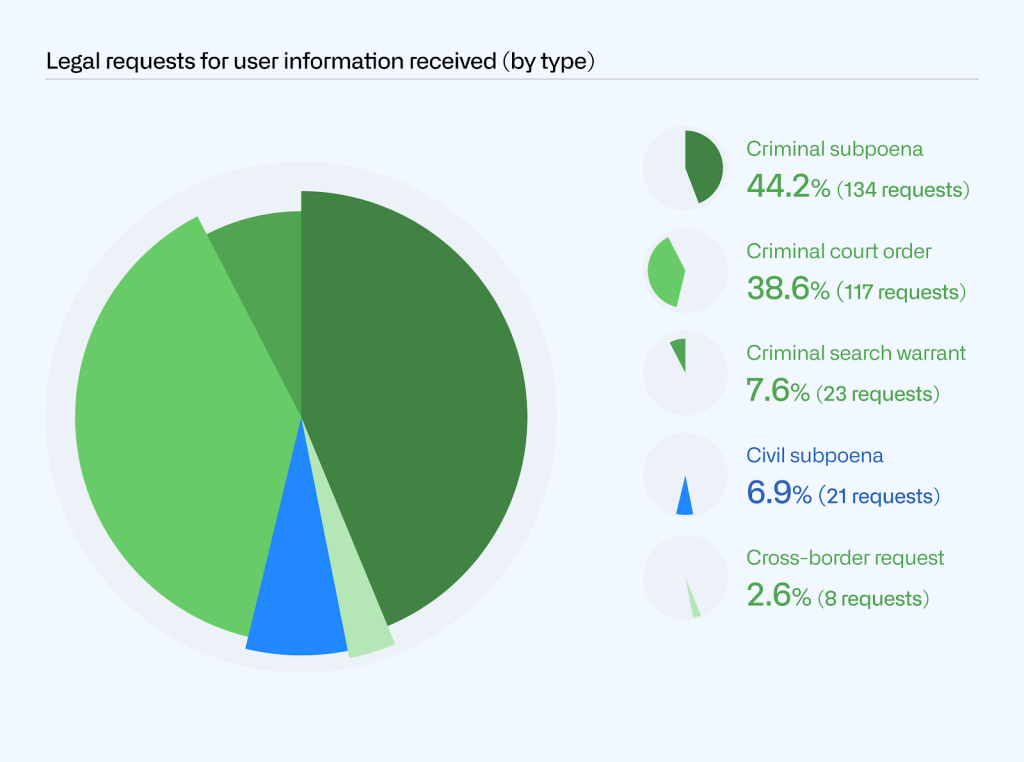

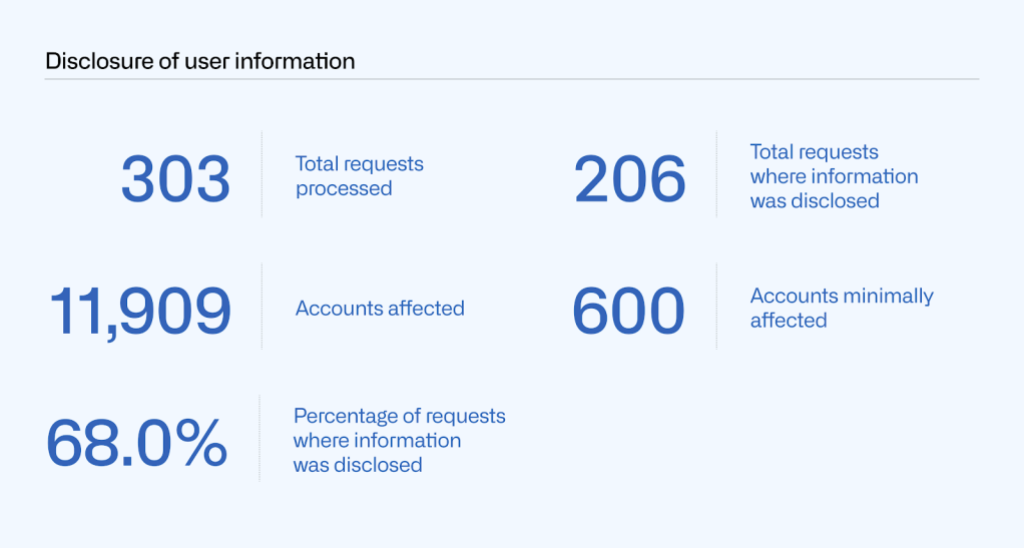

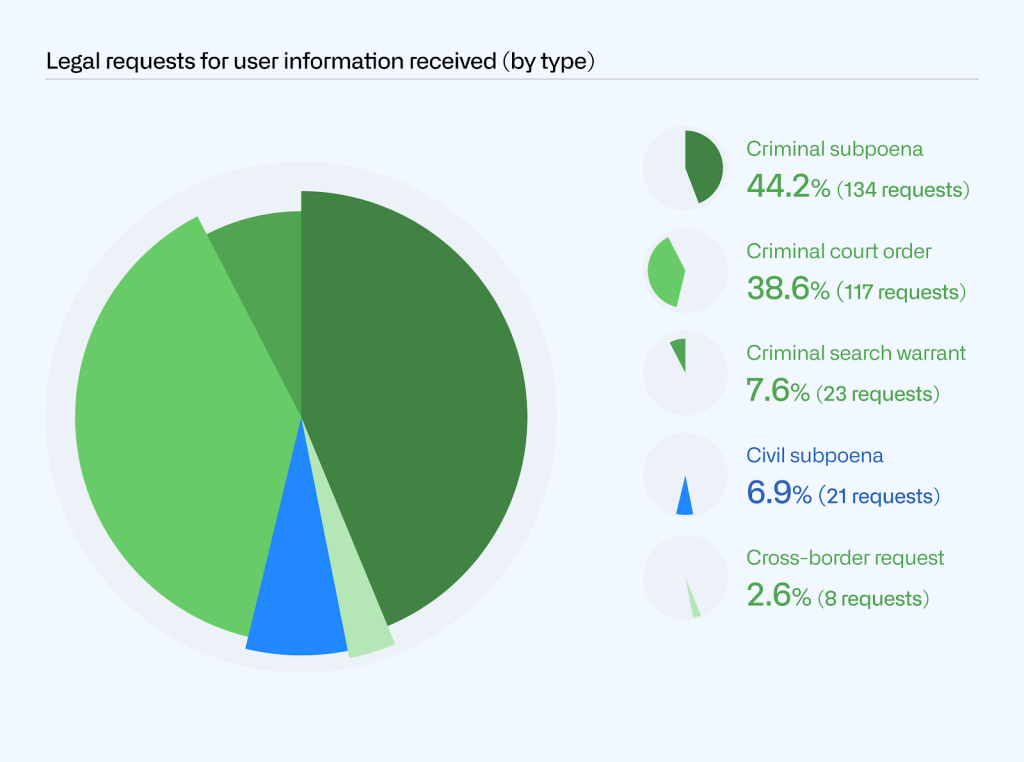

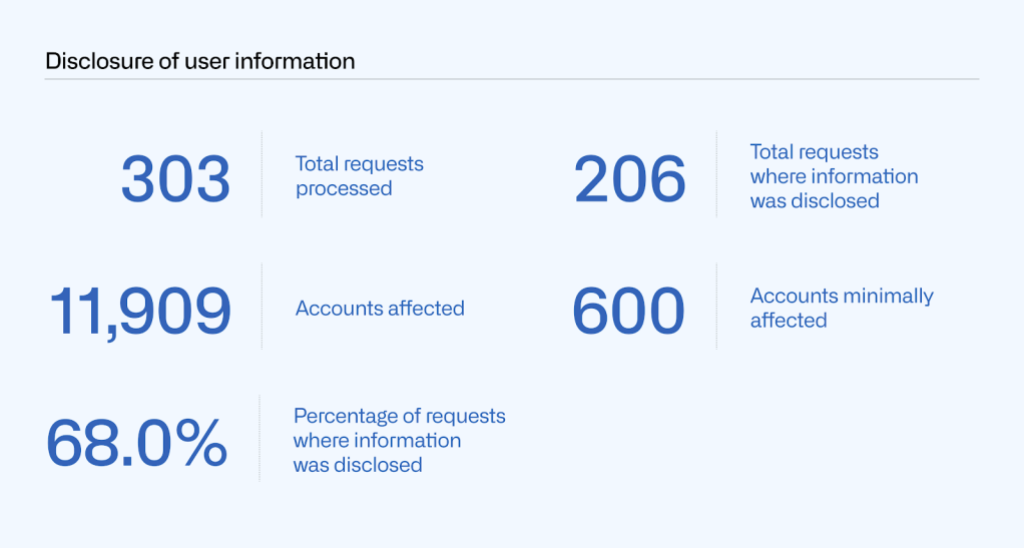

In 2020, GitHub received 303 requests to disclose user information, as compared to 261 in 2019. Of those 303 requests, we processed 155 subpoenas (134 criminal and 21 civil), 117 court orders, and 23 search warrants. These requests also include eight cross-border data requests, which we’ll share more about later in this report. The large majority (93.1%) of these requests came from law enforcement. The remaining 6.9% were civil requests, all of which came from civil litigants wanting information about another party.

These numbers represent every request we received for user information, regardless of whether we disclosed information or not, with one exception: we are prohibited from even stating whether or how many national security letters or orders we received. More information on that below. We’ll cover additional information about disclosure and notification in the next sections.

We carefully vet all requests to disclose user data to ensure they adhere to our policies and satisfy all appropriate legal requirements, and push back where they do not. As a result, we didn’t disclose user information in response to every request we received. In some cases, the request was not specific enough, and the requesting party withdrew the request after we asked for clarification. In other cases, we received very broad requests, and we were able to limit the scope of the information we provided.

When we do disclose information, we never share private content data, except in response to a search warrant. Content data includes, for example, content hosted in private repositories. With all other requests, we only share non-content data, which includes basic account information, such as username and email address, metadata such as information about account usage or permissions, and log data regarding account activity or access history.

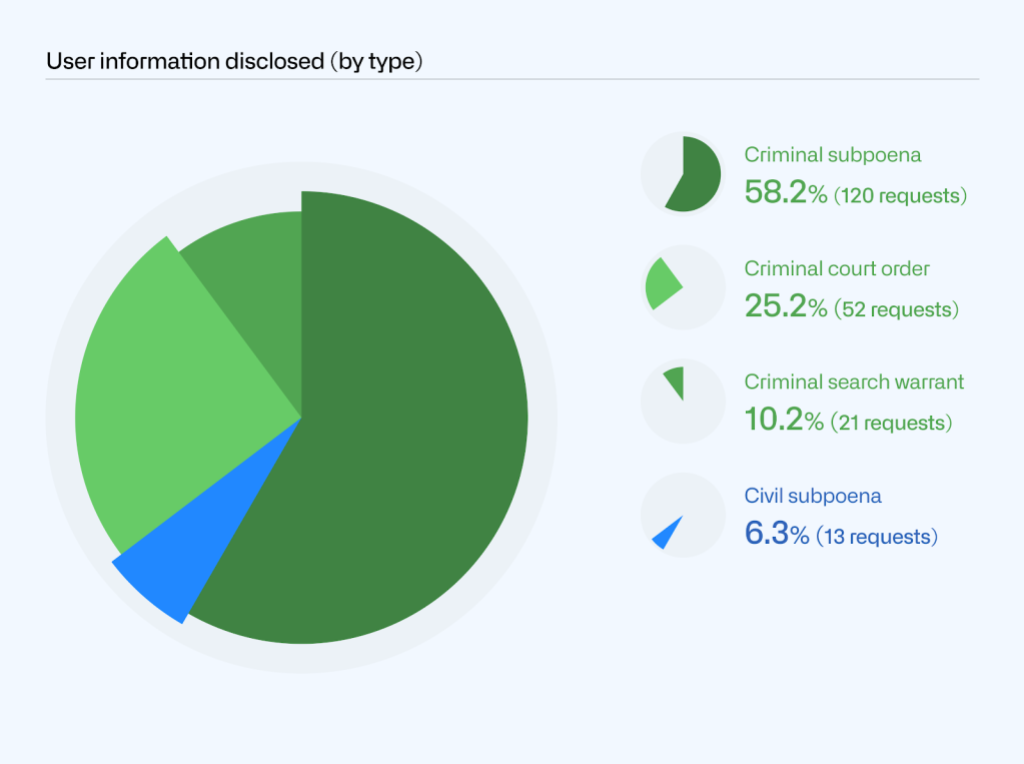

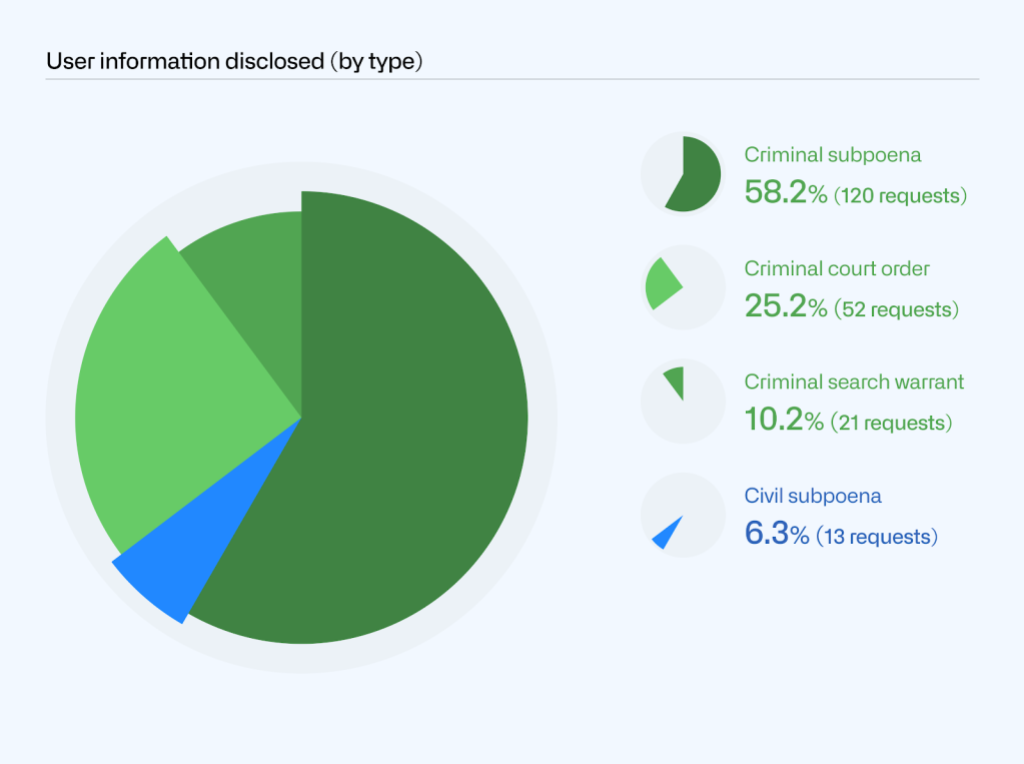

Of the 303 requests we processed in 2020, we disclosed information in response to 206 of those. We disclosed information in response to 133 subpoenas (120 criminal and 13 civil), 52 court orders, and 21 search warrants.

Those 206 disclosures affected 11,909 accounts. Twelve requests account for 11,309 of these affected accounts. Three requests alone affected more than 9,000 accounts, including one that affected more than 6,000 accounts. Not counting those 12 requests, the remaining 291 times we disclosed information affected 600 accounts, approximately two accounts per disclosure on average.

Requests that affect a large number of users typically occur when a court order seeks information about access to a piece of content posted on GitHub or a shared IP address, rather than targeting specific users. In these cases, GitHub endeavors to minimize the information shared about users identified in log data. For example, GitHub will often try to avoid producing any personal information by hashing the data when this will satisfy the request. Where a legal request calls for the production of usernames and IP addresses in the log data, GitHub will typically limit the personal information we share about user accounts to the data in the log entries about access from a specific IP address or to a specific URL. This data may include username, IP address, user agent string, URL path, and referrer path. For the purposes of our reporting, we are referring to these larger log disclosures where we would be sharing that a specific user accessed a specific URL from a specific IP address at a specific time as user accounts that are “minimally affected.” This is because for accounts we count as “minimally affected” we did not produce general account information about that specific user, such as their email address or other contact info, information about their account contents, organization memberships, or their browsing history outside of the specific log entries captured.

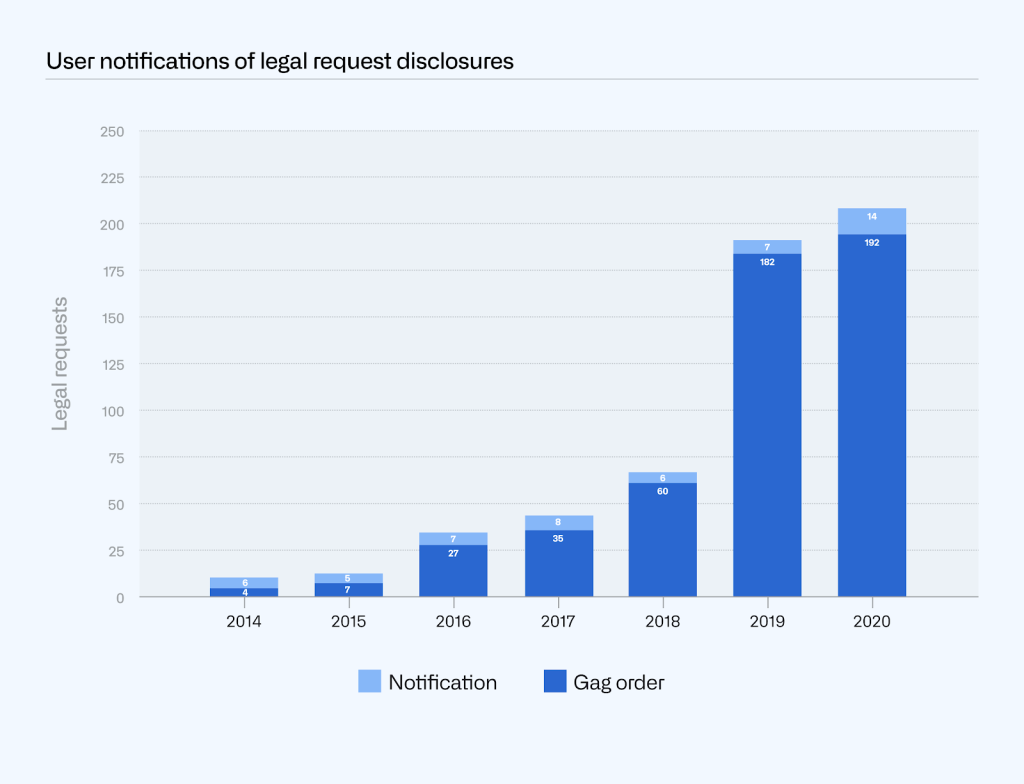

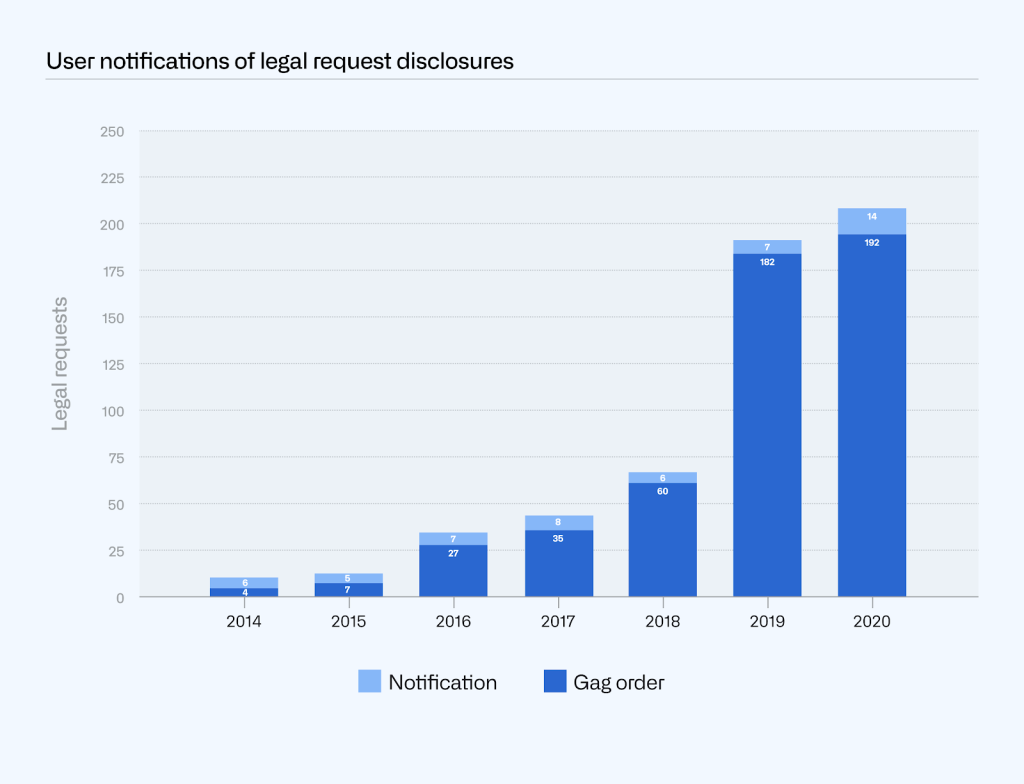

We notify users when we disclose their information in response to a legal request, unless a law or court order prevents us from doing so. In many cases, legal requests are accompanied by a court order that prevents us from notifying users, commonly referred to as a gag order.

Of the 206 times we disclosed information in 2020, we were only able to notify users 14 times because gag orders accompanied the other 192 requests.

While the number of requests with gag orders continues to be a rising trend as a percentage of overall requests, it correlates with the number of criminal requests we processed. Legal requests in criminal matters often come with a gag order, since law enforcement authorities often assert that notification would interfere with the investigation. On the other hand, civil matters are typically public record, and the target of the legal process is often a party to the litigation, obviating the need for any secrecy. None of the civil requests we processed this year came with a gag order, which means we notified each of the affected users.

In 2020, we continue to see a correlation between civil requests we processed (6.9%) and our ability to notify users (6.8%). Our data from the past years also reflects this trend of notification percentages correlating with the percentage of civil requests:

- 3.7% notified and 3.1% civil requests in 2019

- 9.1% notified and 11.6% civil requests in 2018

- 18.6% notified and 23.5% civil requests in 2017

- 20.6% notified and 8.8% civil requests in 2016

- 41.7% notified and 41.7% civil requests in 2015

- 40% notified and 43% civil requests in 2014

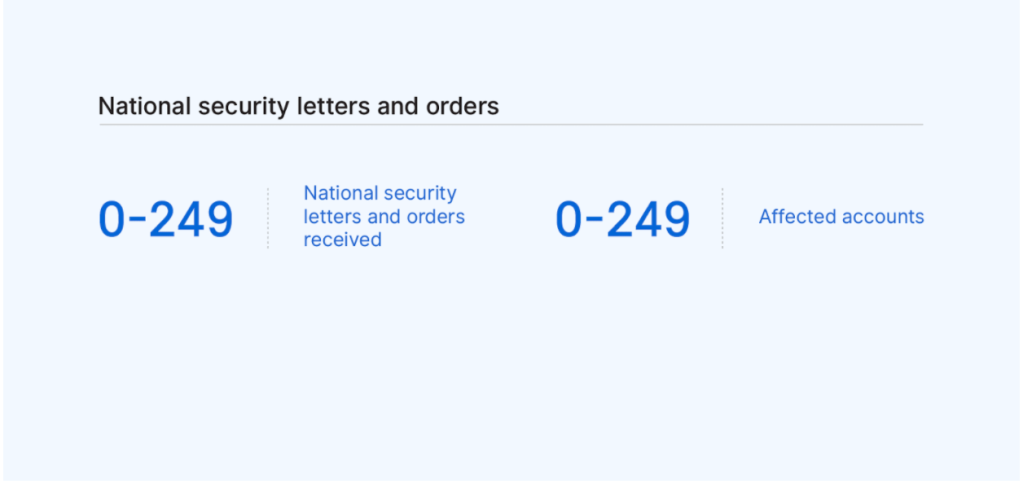

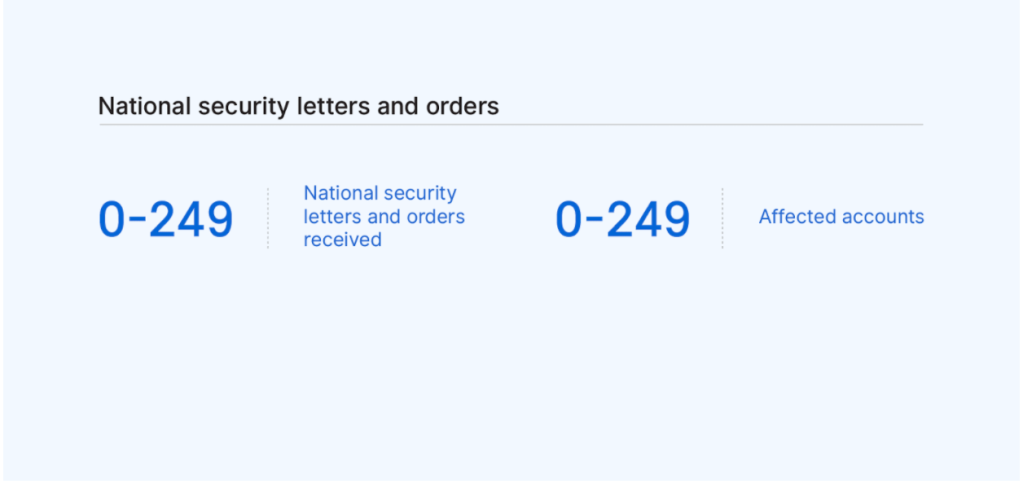

We’re very limited in what we can legally disclose about national security letters and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) orders. The US Department of Justice (DOJ) has issued guidelines that only allow us to report information about these types of requests in ranges of 250, starting with zero. As shown below, we received 0–249 notices in 2019, affecting 0–249 accounts.

Governments outside the US can make cross-border data requests for user information through the DOJ via a mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) or similar form of international legal process. Our Guidelines for Legal Requests of User Data explain how we handle user information requests from foreign law enforcement. Essentially, when a foreign government seeks user information from GitHub, we direct the government to the DOJ so that the DOJ can determine whether the request complies with US legal protections.

If it does, the DOJ would send us a subpoena, court order, or search warrant, which we would then process like any other requests we receive from the US government. When we receive these requests from the DOJ, they don’t necessarily come with enough context for us to know whether they’re originating from another country. However, when they do indicate that, we capture that information in our statistics for subpoenas, court orders, and search warrants. This year, we know that two of those court orders we processed had originated as cross-border requests.

In 2020, we received eight requests directly from foreign governments. Those requests came from two countries, Germany and India. This is similar to 2019, when we also received eight requests, also from Germany and India. Consistent with our guidelines above, in each of those cases we referred those governments to the DOJ to use the MLAT process.

In the next sections, we describe two main categories of requests we receive to remove or block user content: government takedown requests and DMCA takedown notices.

From time to time, GitHub receives requests from governments to remove content that they judge to be unlawful in their local jurisdiction. When we remove content at the request of a government, we limit it to the jurisdiction(s) where the content is illegal—not everywhere—whenever possible. In addition, we always post the official request that led to the block in a public government takedowns repository, creating a public record where people can see that a government asked GitHub to take down content.

When we receive a request, we confirm whether:

- The request came from an official government agency

- An official sent an actual notice identifying the content

- An official specified the source of illegality in that country

If we believe the answer is “yes” to all three, we block the content in the narrowest way we see possible, for example by geoblocking content only in a local jurisdiction.

In 2020, GitHub received and processed 44 government takedown requests based on local laws—all from Russia. These takedowns resulted in 44 projects (36 gists, all or part of five repositories, and three GitHub Pages sites) being blocked in Russia. In comparison, in 2019, we processed 16 takedowns that affected 54 projects. While we processed a significantly higher number of government takedown requests in 2020, there were a smaller number of affected projects overall.

In addition to requests based on violations of local law, GitHub processed 13 requests from governments to take down content as a Terms of Service violation, affecting 12 accounts and one repository in 2020. These requests concerned phishing (Nepal, US, and Sri Lanka), malware (Spain), disinformation (Uruguay), or violations related to other product terms (UK and China).

We denied three government requests that alleged Terms of Service violations, due to lack of evidence that a violation of our Terms had occurred. These requests came from Denmark, Korea, and the US. We also received one request from India in which the content was removed by the account owner prior to our processing the notice.

Consistent with our approach to content moderation across the board, GitHub handles DMCA claims to maximize protections for developers, and we designed our DMCA Takedown Policy with developers in mind. Most content removal requests we receive are submitted under the DMCA, which allows copyright holders to ask GitHub to take down content they believe infringes on their copyright. If the user who posted the allegedly infringing content believes the takedown was a mistake or misidentification, they can then send a counter notice asking GitHub to reinstate the content.

Additionally, before processing a valid takedown notice that alleges that only part of a repository is infringing, or if we see that’s the case, we give users a chance to address the claims identified in the notice first. We also now do this with all valid notices alleging circumvention of a technical protection measure. That way, if the user removes or remediates the specific content identified in the notice, we avoid having to disable any content at all. This is an important element of our DMCA policy, given how much users rely on each other’s code for their projects.

Each time we receive a valid DMCA takedown notice, we redact personal information, as well as any reported URLs where we were unable to determine there was a violation. We then post the notice to a public DMCA repository.

Our DMCA Takedown Policy explains more about the DMCA process, as well as the differences between takedown notices and counter notices. It also sets out the requirements for making a valid request, which include that the person submitting the notice takes into account fair use.

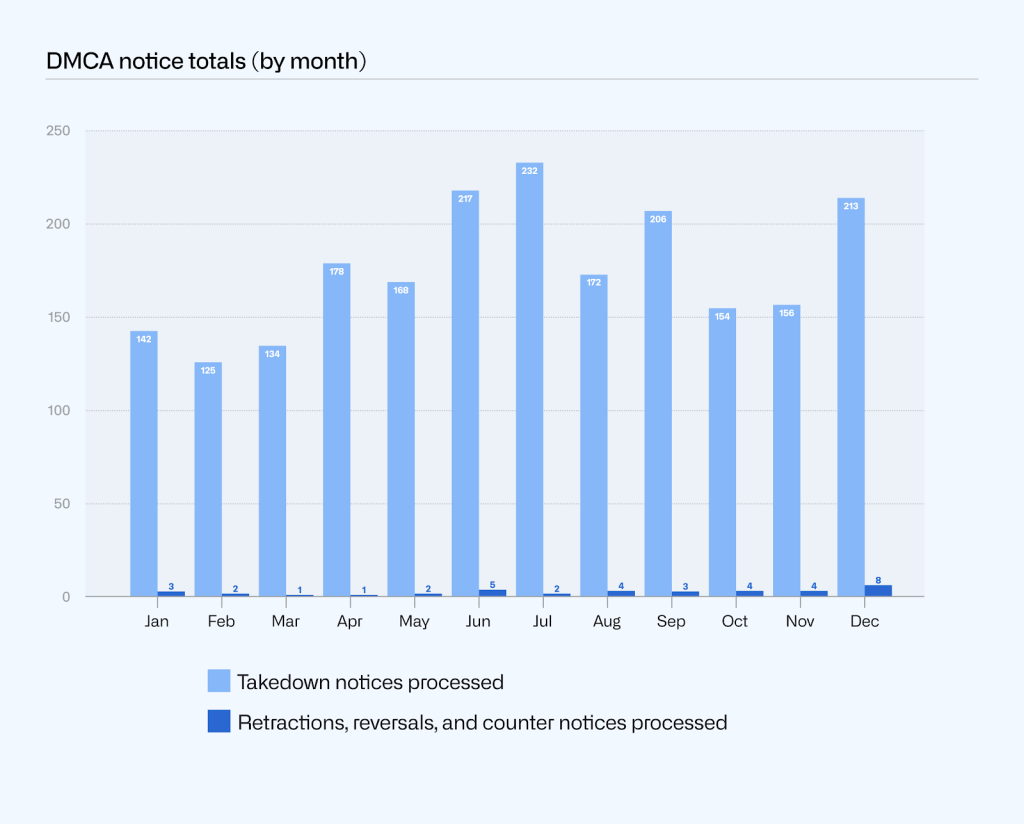

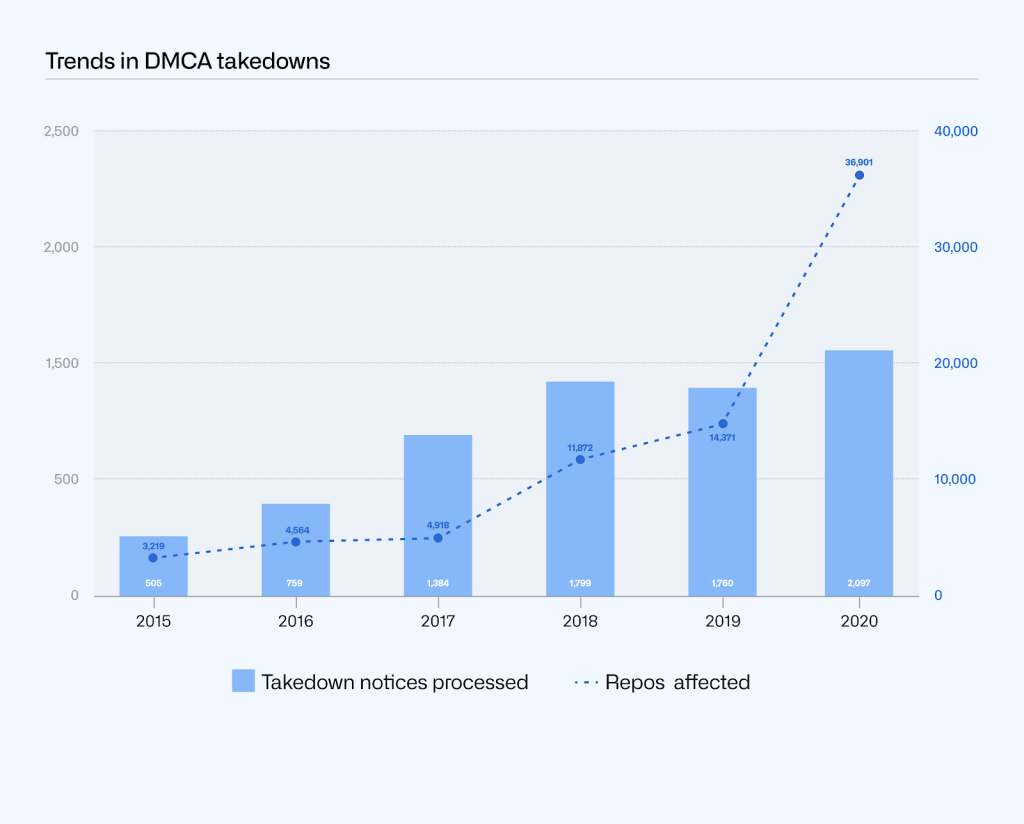

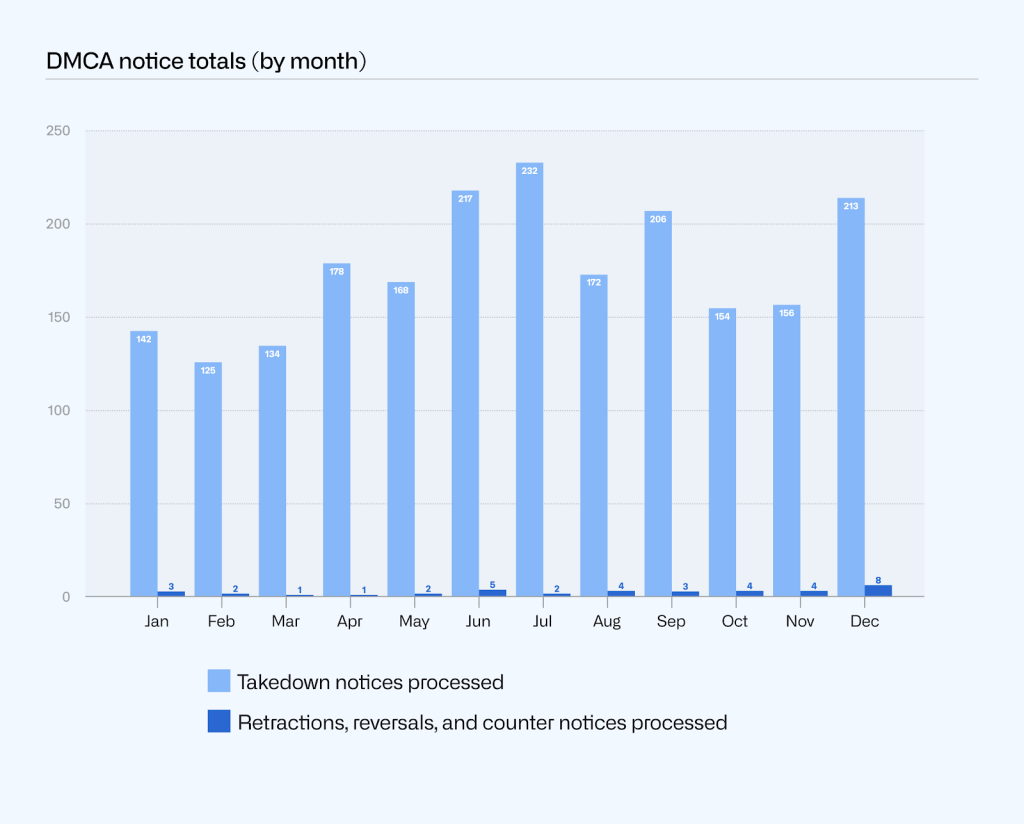

In 2020, GitHub received and processed 2,097 valid DMCA takedown notices. This is the number of separate notices where we took down content or asked our users to remove content. In addition, we received and processed 32 valid counter notices, two retractions, three reversals, one counter notice retraction, and one counter notice reversal, for a total of 2,136 notices in 2020. We also received one notice of legal action filed related to a DMCA takedown request this year.

While content can be taken down, it can also be restored. In some cases, we reinstate content that was taken down if we receive one of the following:

- Counter notice: the person whose content was removed sends us sufficient information to allege that the takedown was the result of a mistake or misidentification.

- Retraction: the person who filed the takedown changes their mind and requests to withdraw it.

- Reversal: after receiving a seemingly complete takedown request, GitHub later receives information that invalidates it, and we reverse our original decision to honor the takedown notice.

These definitions of “retraction” and “reversal” each refer to a takedown request. However, the same can happen with respect to a counter notice. In 2020, we processed one counter notice retraction and one counter notice reversal.

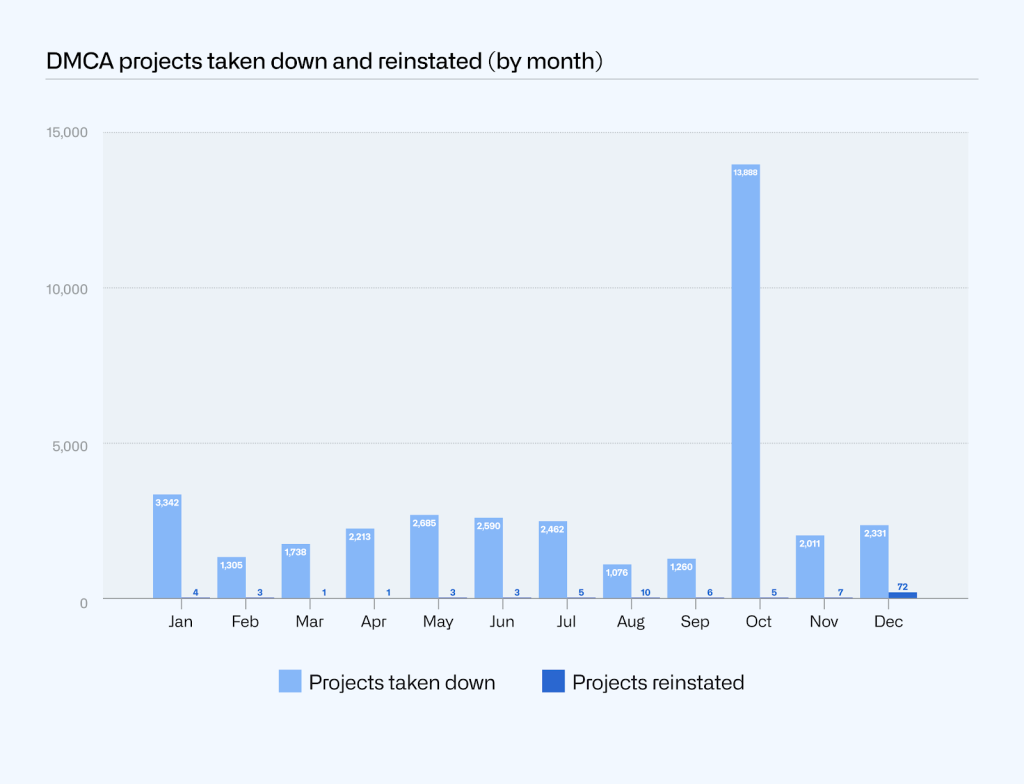

In 2020, the total number of takedown notices ranged from 125 to 232 per month. The monthly totals for counter notices, retractions, and reversals combined ranged from one to eight.

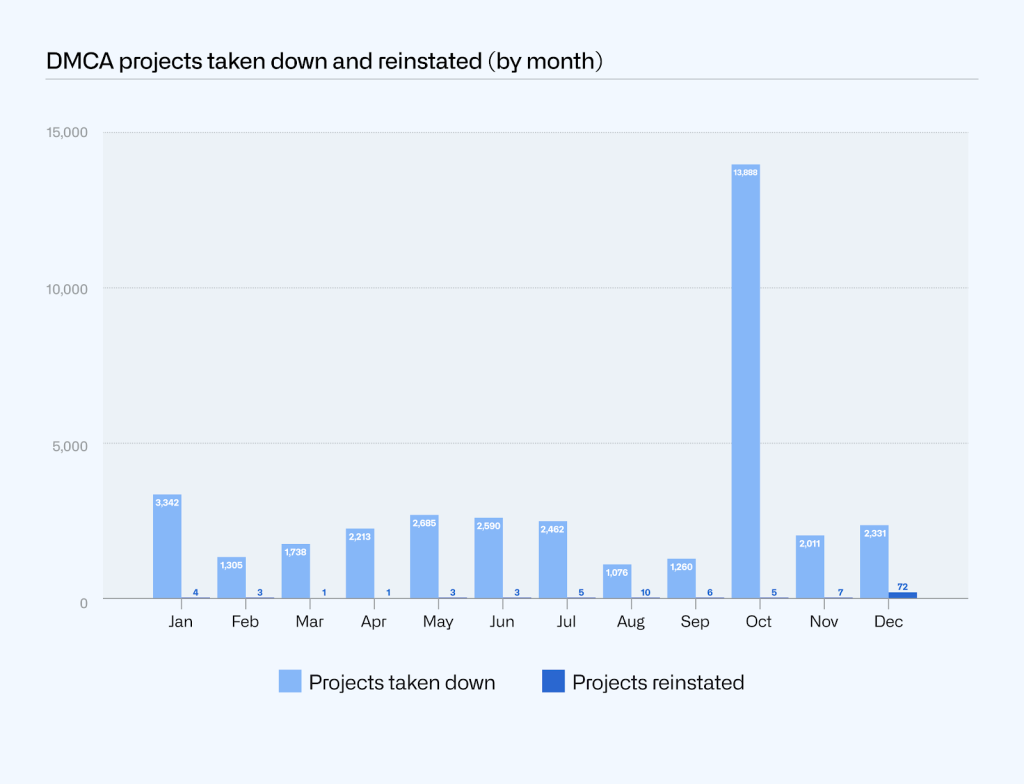

Often, a single takedown notice can encompass more than one project. For these instances, we looked at the total number of projects, including repositories, gists, and GitHub Pages sites that we had taken down due to DMCA takedown requests in 2020. An emblematic example of the potential impact of a DMCA takedown notice is youtube-dl. The large spike in projects taken down in October relates to that one takedown request, which was for a project that had over 12,000 forks at the time of processing (although we’ve since reversed the takedown).

The monthly totals for projects reinstated (based on a counter notice, retraction, or reversal) ranged from one to 46. The number of counter notices, retractions, and reversals we receive amounts to less than one to nearly four percent of the DMCA-related notices we get each month. This means that most of the time when we receive a valid takedown notice, the content comes down and stays down. In total in 2020, we took down 36,901 projects and reinstated 120, which means that 36,173 projects stayed down.

The number 36,173 may sound like a lot of projects, but it’s less than about two one-hundredths of a percent of the repositories on GitHub at the end of 2020.

It’s also counting many projects that are actually currently up. When a user made changes in response to a takedown notice, we count that in the “stayed down” number. Because the reported content stayed down, we include it even if the rest of the project is still up. Those are in addition to the number reinstated.

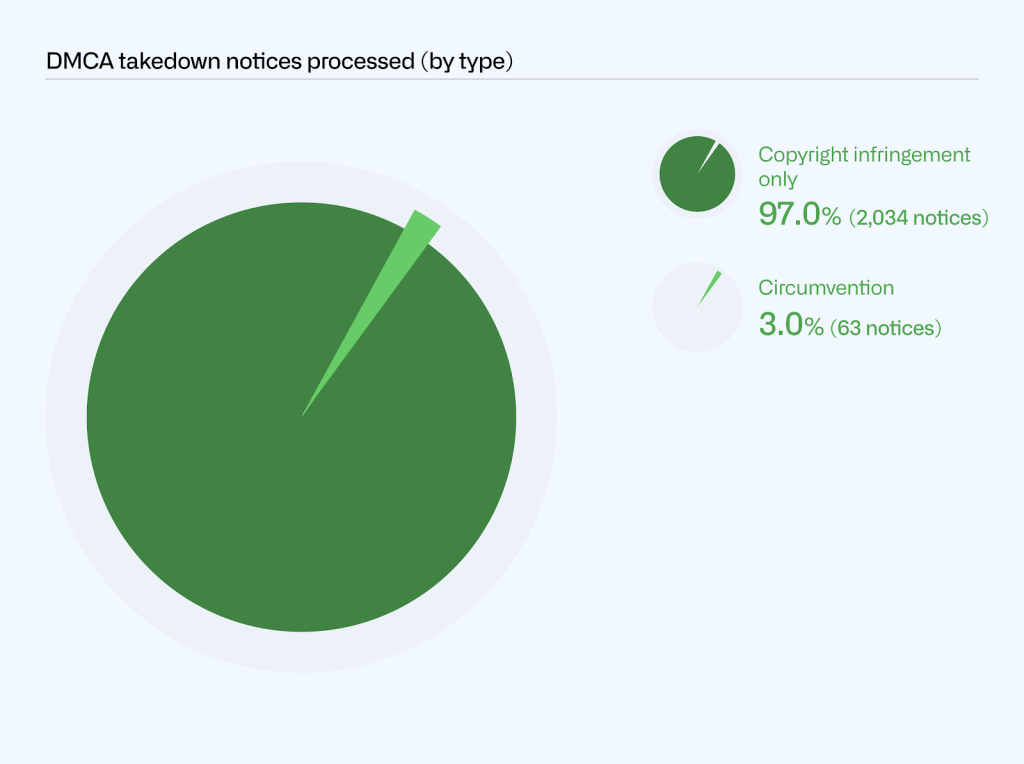

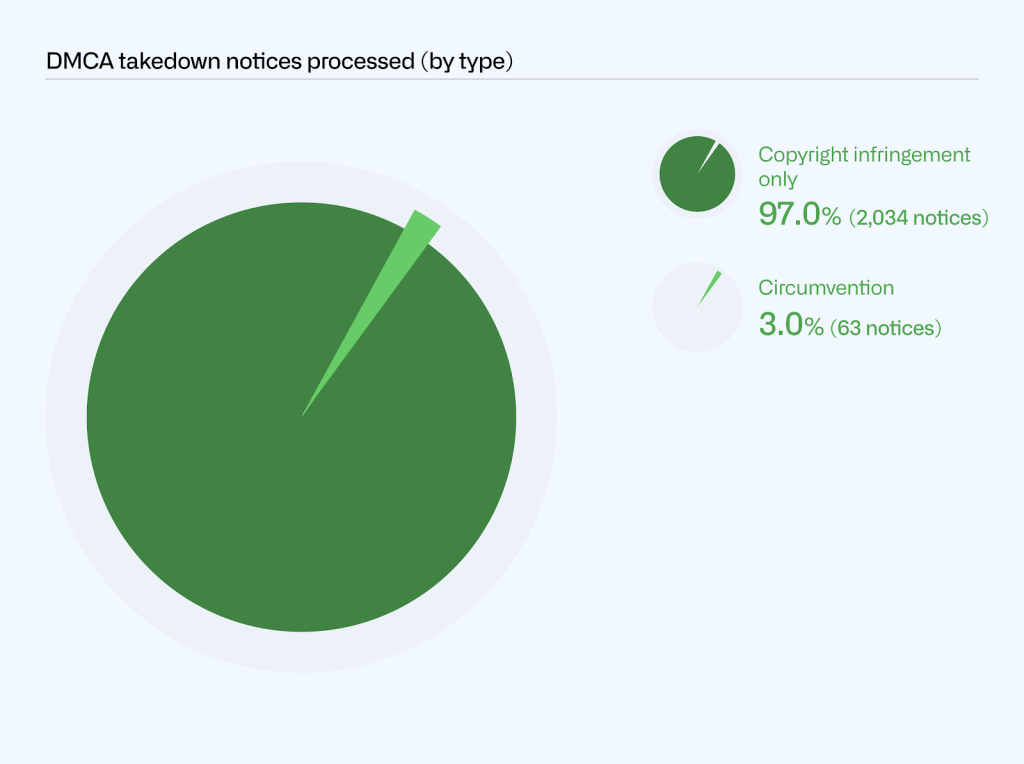

A new addition this year within our DMCA reporting is takedown notices that allege circumvention of a technical protection measure under section 1201 of the DMCA. GitHub requires additional information for a DMCA takedown notice to be complete and actionable where it alleges circumvention. We are able to estimate the number of DMCA notices we processed that include a circumvention claim by searching the takedown notices we processed for relevant keywords. On that basis, we can estimate that of the 2,097 notices we processed in 2020, 63 notices, or 3.0%, related to circumvention. These figures reflect an increase compared to recent years:

- 49 or 2.78% of all notices in 2019

- 33 or 1.83% of notices in 2018

- 25 or 1.81% of notices in 2017

- 36 or 4.74% of notices in 2016

- 18 or 3.56% of notices in 2015

Although takedown notices for circumvention violations have increased in the past few years, they are relatively few, and the proportion of takedown notices related to circumvention has fluctuated between roughly two and five percent of all takedown notices. Following the youtube-dl reinstatement, we are even more committed to our developer-first promise and have been working on new ways to more closely track and report on this data in future transparency reports.

All of those numbers were about valid notices we received. We also received a lot of incomplete or insufficient notices regarding copyright infringement. Because these notices do not result in us taking down content, we do not currently keep track of how many incomplete notices we receive, or how often our users are able to work out their issues without sending a takedown notice.

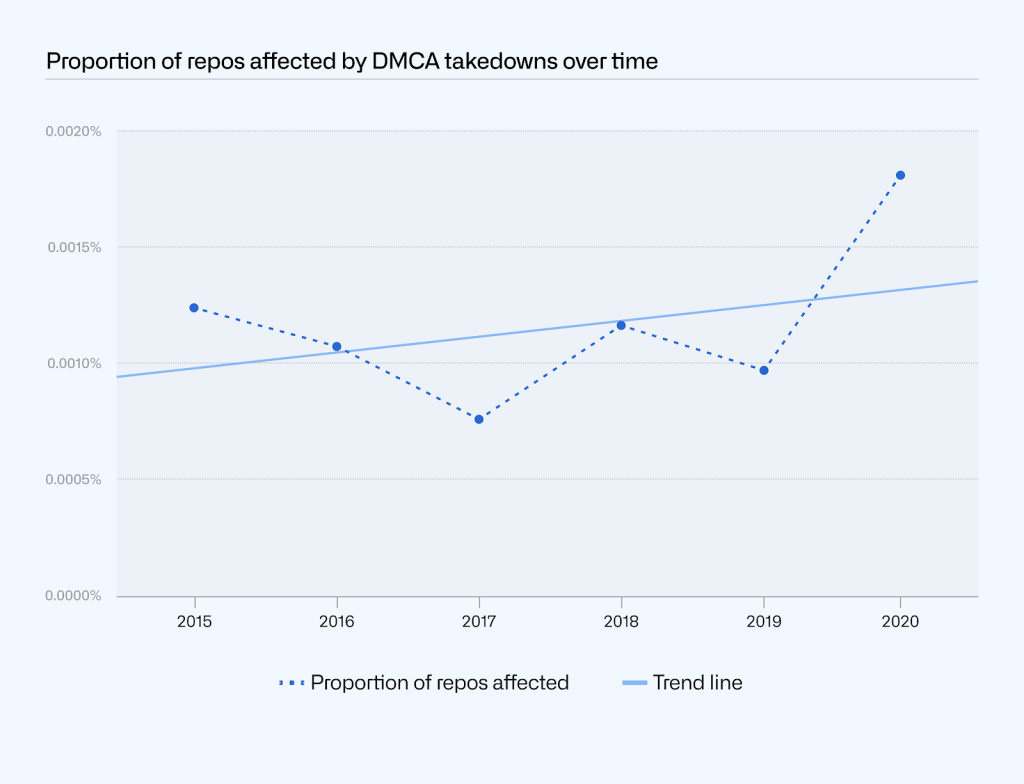

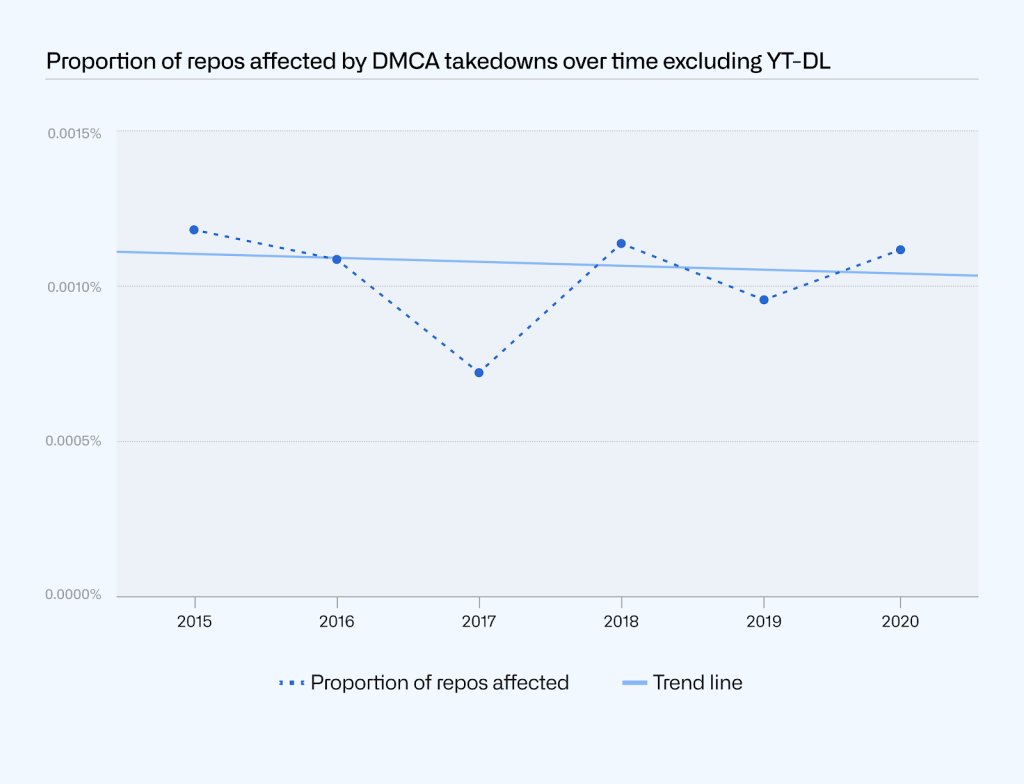

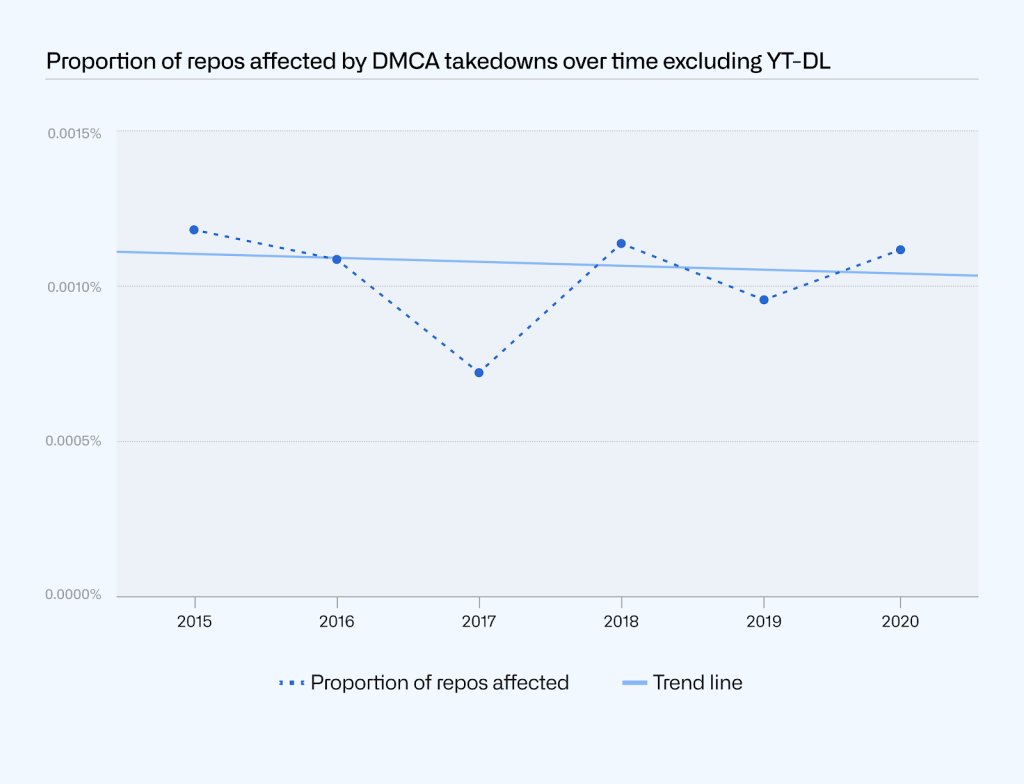

Based on DMCA data we’ve compiled over the last few years, we have seen an increase in DMCA notices received and processed. This increase is closely correlated with growth in repositories over the same period of time, so the proportion of repositories affected by takedowns has remained relatively consistent over time. This trend is clearer when excluding the outlier youtube-dl takedown from the dataset.

A new category this year is reinstatements, including as a result of appeals. Reinstatements can occur when we undo an action we had taken to disable a repository, hide an account, or suspend a user’s access to their account in response to a Terms of Service violation. While sometimes this happens because a user disputes a decision to restrict access to their content (an appeal), in many cases, we reinstate an account or repository after a user removes content that violated our Terms of Service and agrees not to violate them going forward. For the purposes of this report, we looked at reinstatements related to:

- Abuse: violations of our Acceptable Use Policies, except for spam and malware

- Trade controls: violations of trade sanctions restrictions

GitHub’s Terms of Service include content and conduct restrictions, set out in our Acceptable Use Policies and Community Guidelines. These restrictions include discriminatory content, doxxing, harassment, sexually obscene content, inciting violence, disinformation, and impersonation. Note: For the purposes of this report, we do not include appeals related to spam or malware, though our Terms of Service do restrict those kinds of content too.

When we determine a violation of our Terms of Service has occurred, we have a number of enforcement actions we can take. In keeping with our approach of restricting content in the narrowest way possible to address the violation, sometimes we can resolve an issue by disabling one repository (taking down one project) rather than acting on an entire account. Other times, we may need to act at the account level, for example, if the same user is committing the same violation across several repositories.

At the account level, in some cases we will only need to hide a user’s account content—for example, when the violation is based on content being publicly posted—while still giving the user the ability to access their account. In other cases, we will only need to restrict a user’s access to their account—for example, when the violation is based on their interaction with other users—while still giving other users the ability to access their shared content. For a collaborative software development platform like GitHub, we realized we need to provide this option so that other users can still access content that they might want to use for their projects.

We reported on restrictions and reinstatements by type of action taken. In 2020, we hid 4,826 accounts and reinstated 415 hidden accounts. We restricted an account owner’s access to 47 accounts and reinstated it for 15 accounts. For 1,178 accounts, we both hid and restricted the account owner’s access, lifting both of those restrictions to fully reinstate 29 accounts and lifting one but not the other to partially reinstate 12 accounts. As for abuse-related restrictions at the project level, we disabled 2,405 projects and reinstated only four in 2020. These do not count DMCA related takedowns or reinstatements (for example due to counter notices), which are reported on in the DMCA section, above).

We’re dedicated to empowering as many developers around the world as possible to collaborate on GitHub. The US government has imposed sanctions on several countries and regions (Crimea, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, and Syria), which means GitHub isn’t fully available in all of those places. However, GitHub will continue advocating with US regulators for the greatest possible access to code collaboration services to developers in sanctioned regions. For example, we recently secured a license from the US government to make all GitHub services fully available to developers in Iran. Because we reinstated the affected accounts in 2021, this development is not reflected in the 2020 statistics reported below. We are continuing to work toward a similar outcome for developers in Crimea and Syria, as well as other sanctioned regions. Our services are also generally available to developers located in Cuba, aside from specially designated nationals, including certain government officials.

Although trade control laws require GitHub to restrict account access from certain regions, we enable users to appeal these restrictions, and we work with them to restore as many accounts as we legally can. In many cases, we can reinstate a user’s account (grant an appeal), for example after they returned from temporarily traveling to a restricted region or if their account was flagged in error. More information on GitHub and trade controls can be found here.

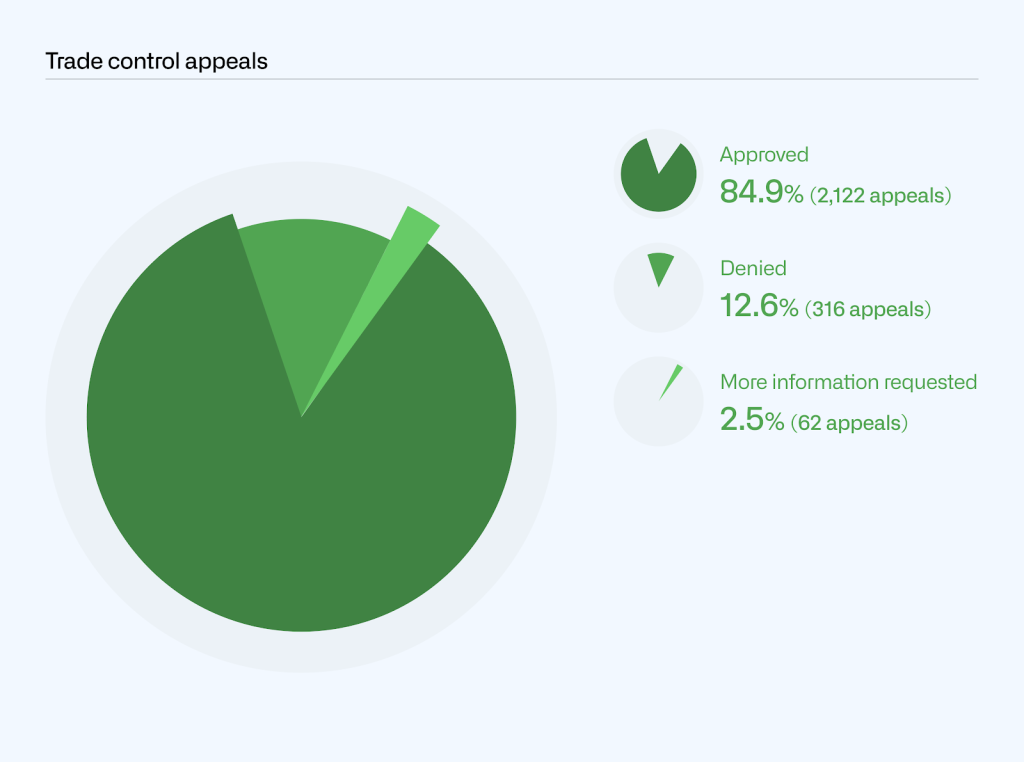

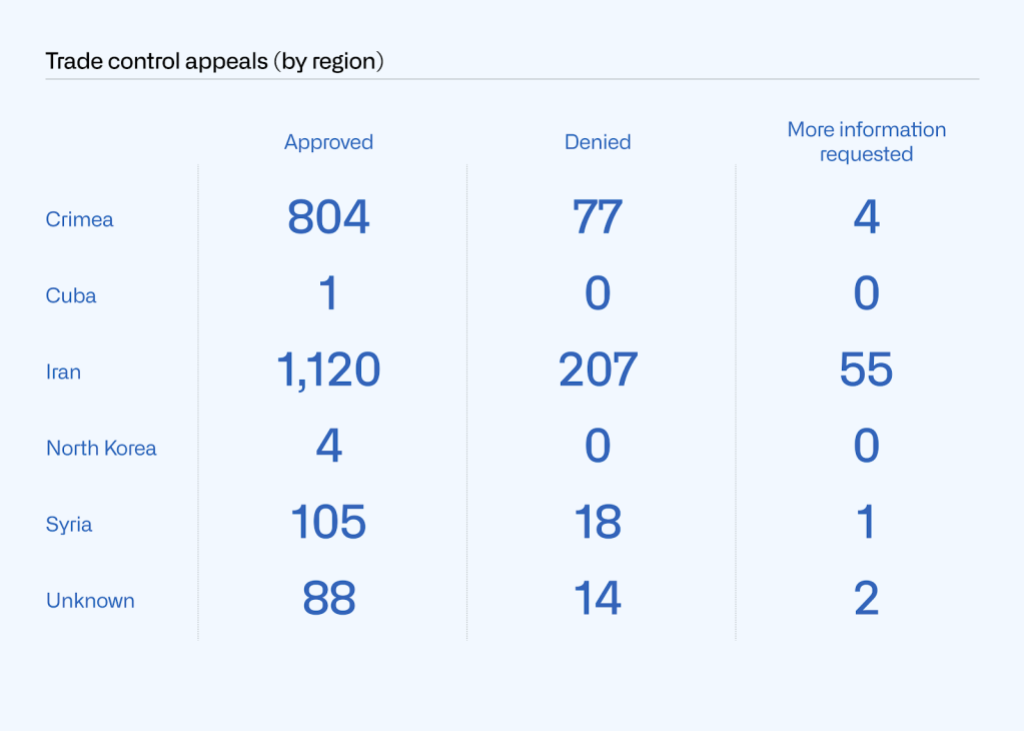

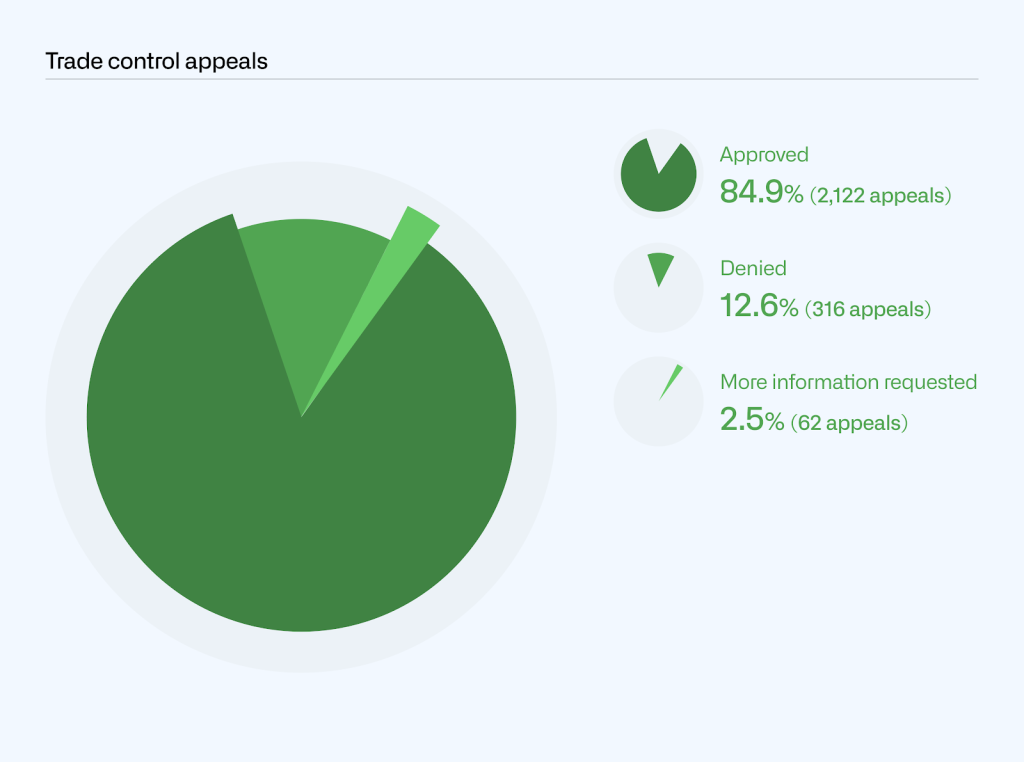

We started tracking sanctions-related appeals in July 2019. Unlike abuse-related violations, we must always act at the account level (as opposed to being able to disable a repository) because trade controls laws require us to restrict a user’s access to GitHub. In 2020, 2,500 users appealed trade-control related account restrictions, and 1,495 in the second half of 2019. Of the 2,500 appeals we received in 2020, we approved 2,122 and denied 316, and required further information to process in 62 cases. We also received 36 appeals that were mistakenly filed by users who were not subject to trade controls so we excluded from our analysis below.

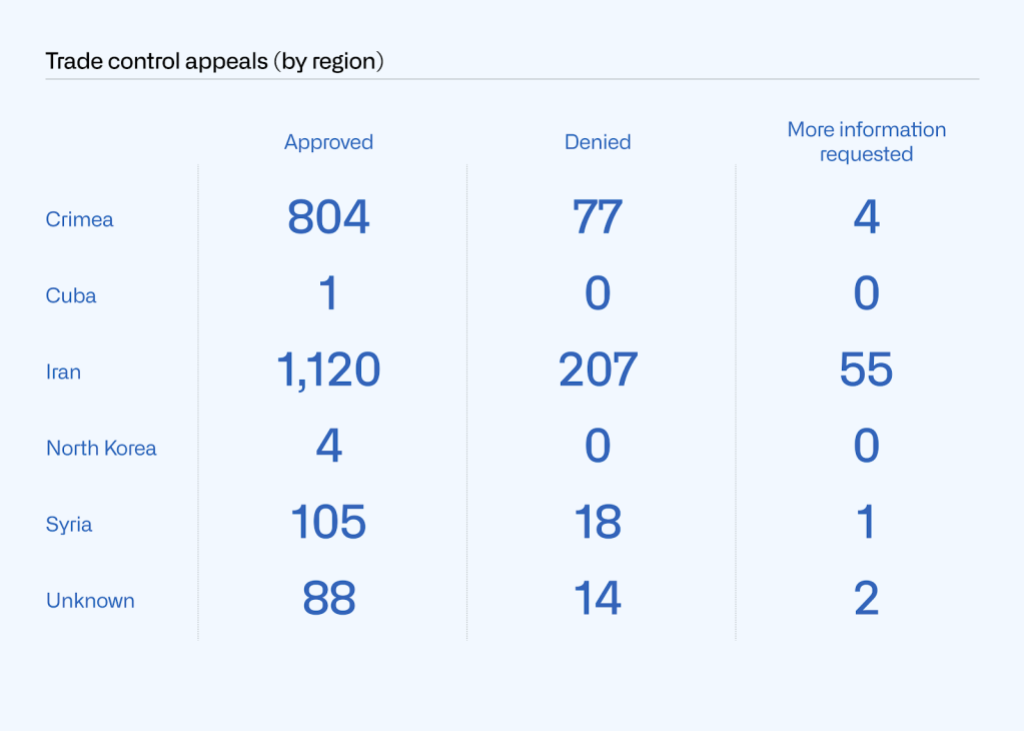

Appeals varied widely by region, with hundreds reported from Crimea and Iran, and only single digits from Cuba and North Korea. In 104 cases, we were unable to assign an appeal to a region in our data. We marked them as “Unknown” in the table below and excluded them from regional totals in the chart below it.

GitHub remains committed to maintaining transparency and promoting free expression as an essential part of our commitment to developers. We aim to lead by example in our approach to transparency by providing in-depth explanation of the areas of content removal that are most relevant to developers and software development platforms. This year, we expanded our transparency reporting to cover some additional areas of interest to developers, like circumvention-related copyright takedowns and sanctions-related appeals. Key to our commitment is ensuring we minimize the amount of data we disclose or the amount of content we take down as much as legally possible. Through our transparency reports, we’re continuing to shed light on our own practices, while also hoping to contribute to broader discourse on platform governance.

We hope you found this year’s report to be helpful and encourage you to let us know if you have suggestions for additions to future reports. For more on how we develop GitHub’s policies and procedures, check out our site policy repository.

Written by

I'm GitHub's Director of Platform Policy and Counsel, building and guiding implementation of GitHub’s approach to content moderation. My work focuses on developing GitHub’s policy positions, providing legal support on content policy development and enforcement, and engaging with policymakers to support policy outcomes that empower developers and shape the future of software.