2022 Transparency Report

Looking back over a year’s worth of developer-first content moderation and, new in this report, making our data more accessible to researchers.

At GitHub, we put developers first and work hard to provide a safe, open, and inclusive platform for code collaboration. Because the world is increasingly reliant upon the availability and limited disruption of code, we’ve developed policies to ensure that code remains available unless there is a clear and legitimate basis for removal or disruption. This means we are committed to minimizing the disruption of software projects, protecting developer privacy, taking action on abusive content, and being transparent with developers about content moderation and disclosure of user information. This kind of transparency is vital for informing our users about potential impacts on privacy, access to information, and the ability to dispute decisions that affect their content. With that in mind, we’ve published transparency reports going back nine years to inform the developer community about GitHub’s content moderation and disclosure of user information.

We continue to strive for excellence in our transparency reports by pursuing reporting that reflects the spirit of the Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation and by following the guidelines set forth in the United Nations report on content moderation.

We promote transparency by:

- Developing our policies in public by open sourcing them so that our users can provide input and track changes

- Explaining our reasons for making policy decisions

- Notifying users when we need to restrict content, and why, whenever possible

- Allowing users to appeal removal of their content

- Publicly posting all Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and government takedown requests we process in a public repository in real time

- New with this report: We’re providing structured data files for the data contained in this transparency report, and we’ll be gradually backfilling data published in previous years’ reports

We limit content removal, in line with lawful limitations, as much as possible by:

- Aligning our Acceptable Use Policies with restrictions on free expression, for example, on hate speech, under international human rights law.

- Providing users an opportunity to remediate or remove specific content rather than blocking entire repositories, when we see that is possible.

- Restricting access to content only in those jurisdictions where it is illegal (geoblocking), rather than removing it for all users worldwide.

- Before removing content based on alleged circumvention of copyright controls (under Section 1201 of the US DMCA or similar laws in other countries), we carefully review both the legal and technical claims, and we sponsor a Developer Defense Fund to provide developers with meaningful access to legal resources to guard against abuse when their code projects are legally challenged.

What’s included in this report

In this Transparency Report, we’ll review stats from January to December 2022 for the following:

- Requests to disclose user information

- Subpoenas

- Court orders

- Search warrants

- National security letters and orders

- Cross-border data requests

- Government requests to remove or block user content

- Under a local law

- Under our Terms of Service

- Takedown notices under the DMCA

- Notices to take down content that allegedly infringes copyright

- Notices to take down content that allegedly circumvents a technical protection measure

- Automated detection

- Child sexual exploitation and abuse imagery

- Terrorist or extremist content

- Appeals

- Acceptable Use Policies violations

- Trade sanctions compliance

Continue reading for more details. If you’re unfamiliar with any of the GitHub terminology we use in this report, please refer to the GitHub Glossary.

Requests to disclose user information

Our guidelines for requests to disclose user information

GitHub’s Guidelines for Legal Requests of User Data explain how we handle legally authorized requests, including law enforcement requests, subpoenas, court orders, and search warrants, as well as national security letters and orders.

We follow the law while requiring adherence to the highest legal standards for user requests for data. Some kinds of legally authorized requests for user data, typically limited in scope, do not require review by a judge or a magistrate. For example, both subpoenas and national security letters are written orders to compel someone to produce documents or testify on a particular subject, and neither requires judicial review. National security letters are further limited in that they can only be used for matters of national security.

By contrast, search warrants and court orders both require judicial review. A national security order is a type of court order that can be put in place, for example, to produce information or authorize surveillance. National security orders are issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a specialized US court for national security matters.

As we note in our guidelines:

- We only release information to third parties when the appropriate legal requirements have been satisfied, or where we believe it’s necessary to comply with our legal requirements, or to prevent an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to a person.

- We require a subpoena to disclose certain kinds of user information, like a name, an email address, or an IP address associated with an account, unless under rare, exigent circumstances. Exigent circumstances refers to cases where we determine that disclosure is necessary to prevent an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to a person, and we keep disclosure as limited as possible in relation to the emergency.

- We require a court order or search warrant for all other kinds of user information, like user access logs and account settings. We require a search warrant for private account contents, such as the contents of a private repository.

- We notify all affected users about any requests for their account information, except where we are prohibited from doing so by law or court order.

Go to our transparency data repo for structured data files of requests to disclose user information.

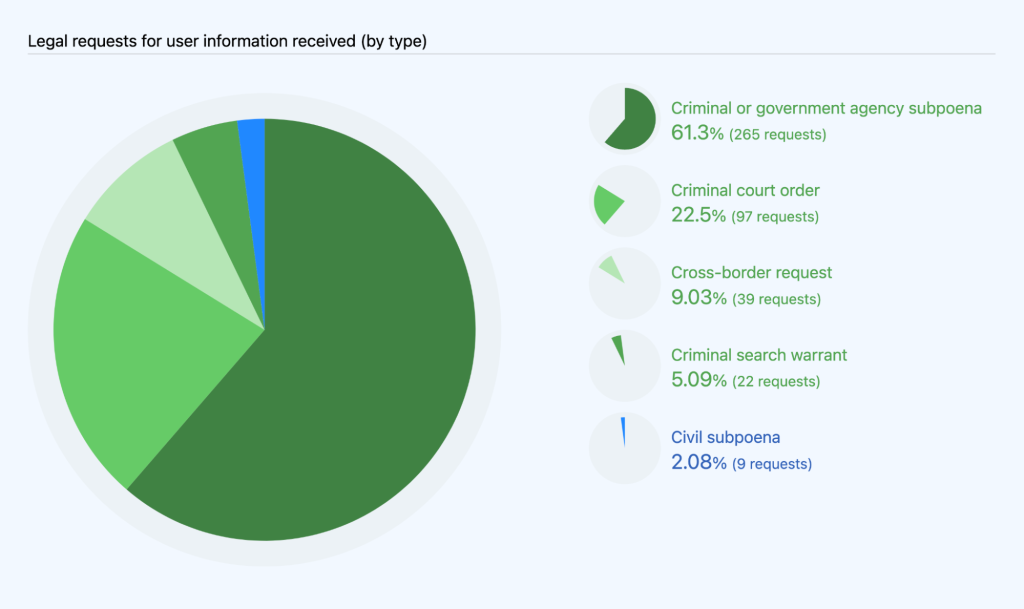

In 2022, GitHub received and processed 432 requests to disclose user information, as compared to 335 in 2021. Of those 432 requests, 274 were subpoenas (with 265 of those subpoenas being criminal or from government agencies and 9 being civil), 97 were court orders, and 22 were search warrants. These requests also include 39 cross-border data requests, which we’ll share more about later in this report. These numbers represent every request we received for user information, regardless of whether we disclosed information or not, with one exception: we are prohibited from stating whether or how many national security letters or orders we received. You can find more information on that below. We’ll cover additional information about disclosure and notification in the next sections.

The large majority (97.9%) of these requests came from law enforcement or government agencies. The remaining 2.1% were civil requests, all of which came from civil litigants seeking information about another party.

Legal requests for user information received (by type)

Disclosure and notification

How we review requests to disclose user information

We carefully review all requests to disclose user data to ensure they adhere to our policies and satisfy all appropriate legal requirements, and we push back where they do not. As a result, we didn’t disclose user information in response to every request we received. In some cases, the request was not specific enough, and the requesting party withdrew the request after we asked for clarification. In other cases, we received very broad requests, and we were able to limit the scope of the information we provided.

When we do disclose information, we never share private content data, except in response to a search warrant. Content data includes, for example, content hosted in private repositories. With all other requests, we only share non-content data, which includes basic account information, such as username and email address, metadata (such as information about account usage or permissions), and log data regarding account activity or access history.

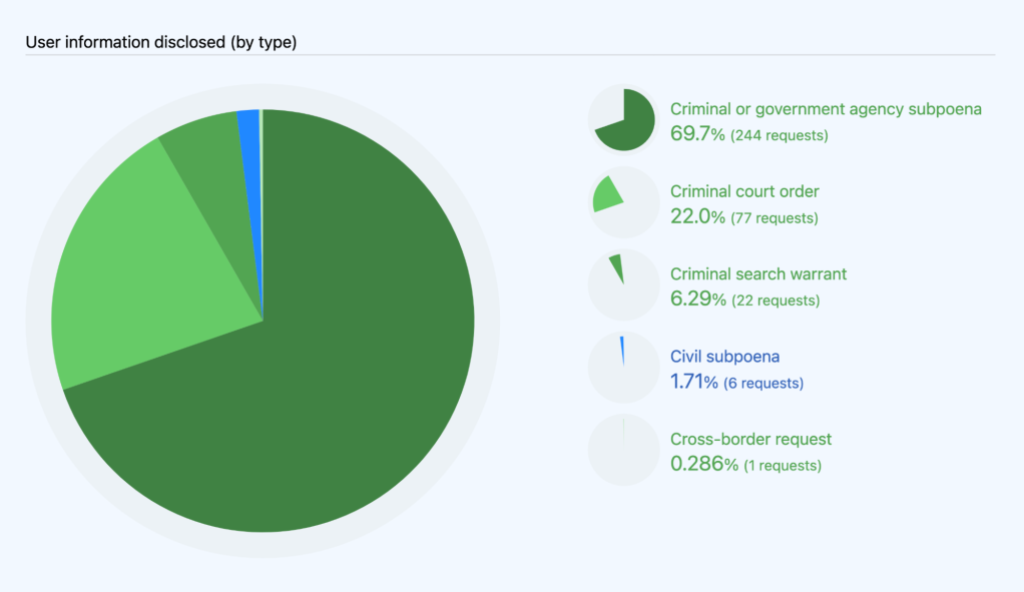

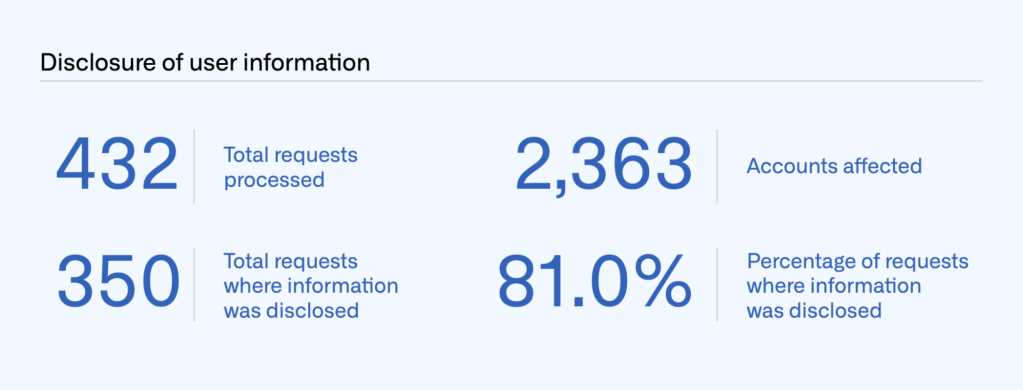

Of the 432 requests we received in 2022, we disclosed information in response to 350 of those. We disclosed information in response to 250 subpoenas (244 criminal and 6 civil), 77 court orders, and 22 search warrants.

User information disclosed (by type)

Those 350 disclosures affected 2,363 accounts.

Disclosure of user information summary

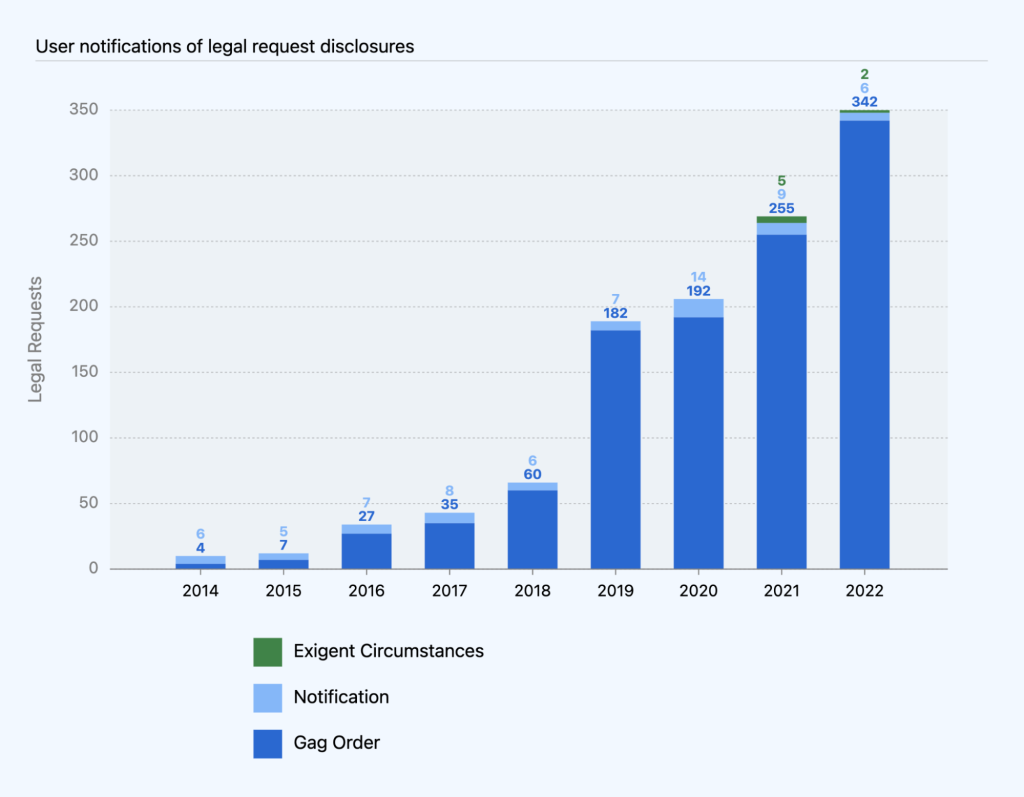

We notify users when we disclose their information in response to a legal request, unless a law or court order prevents us from doing so. In many cases, legal requests are accompanied by a court order that prevents us from notifying users, commonly referred to as a gag order.

Of the 350 times we disclosed information in 2022, we were only able to notify users six times. Gag orders prevented us from notifying users in 342 of the other requests. The other two were processed under exigent circumstances, where we delay notification if we determine it is necessary to prevent death or serious harm or due to an ongoing investigation. Note: prior to 2021, we tracked exigent circumstances requests as part of requests where we disclosed but could not notify.

While the number of requests with gag orders continues to be a rising trend as a percentage of overall requests, it correlates with the number of criminal requests we processed. Legal requests in criminal matters often come with a gag order, since law enforcement authorities often assert that notification would interfere with the investigation. On the other hand, civil matters are typically public record, and the target of the legal process is often a party to the litigation, obviating the need for any secrecy. One out of the six civil requests we processed this year came with a gag order, which means we notified each of the affected users involved in all but one of the requests.

In 2022, we continued to see a correlation between civil requests we processed (2.08%) and our ability to notify users (1.7%). Our data from past years also reflects this trend of notification percentages correlating with the percentage of civil requests:

- 2.7% notified and 2.4% civil requests in 2021

- 3.3% notified and 3.0% civil requests in 2020

- 3.7% notified and 3.1% civil requests in 2019

- 9.1% notified and 11.6% civil requests in 2018

- 18.6% notified and 23.5% civil requests in 2017

- 20.6% notified and 8.8% civil requests in 2016

- 41.7% notified and 41.7% civil requests in 2015

- 40% notified and 43% civil requests in 2014

National security letters and orders

We’re very limited in what we can legally disclose about national security letters and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) orders. We report information about these types of requests in ranges of 250, starting with zero. As shown below, we received 0–249 notices from July to December 2022, affecting 250–499 accounts.

Cross-border data requests

How we handle user information requests from foreign governments

Governments outside the US can make cross-border data requests for user information through the DOJ via a mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) or similar form of international legal process. Our Guidelines for Legal Requests of User Data explain how we handle user information requests from foreign law enforcement. Essentially, when a foreign government seeks user information from GitHub, we direct the government to the DOJ so that the DOJ can determine whether the request complies with US legal protections.

If it does, the DOJ would send us a subpoena, court order, or search warrant, which we would then process like any other request we receive from the US government. When we receive these requests from the DOJ, they don’t necessarily come with enough context for us to know whether they’re originating from another country. However, when a request does indicate this, we capture that information in our statistics for subpoenas, court orders, and search warrants. This year, none of the legal requests we processed originated as cross-border requests.

In 2022, we received 40 requests directly from foreign governments. Those requests came from 12 countries: one from Argentina, four from Brazil, one from Bulgaria, one from Estonia, four from France, 22 from India, one from the Republic of San Marino, one from Spain, one from Switzerland, and one from Ukraine. This is an increase compared to 2021, when we received eighteen requests from five countries. Consistent with our guidelines above, in each of those cases we referred those governments to the DOJ to use the MLAT process.

In the next sections, we describe two main categories of requests we receive to remove or block user content: government takedown requests and DMCA takedown notices.

Government takedowns

How we handle government requests to take down content in local jurisdictions

From time to time, GitHub receives requests from governments to remove content that they judge to be unlawful in their local jurisdiction. When we remove content at the request of a government, we limit it to only the jurisdiction(s) where the content is illegal whenever possible. In addition, we always post the official request that led to the block in a public government takedown repository, creating a public record where people can see that a government asked GitHub to take down content.

When we receive a request, we confirm whether:

- The request came from an official government agency.

- An official sent an actual notice identifying the content.

- An official specified the source of illegality in that country.

If we determine the answer is “yes” to all three, we block the content in the narrowest way we see possible, for example, by geoblocking content only in a local jurisdiction.

In 2022, GitHub received six government takedown requests from Russia, none of which resulted in a takedown. In comparison, in 2021, we processed 26 takedowns that affected 69 projects from Russia, China, and Hong Kong. We have processed a significantly lower number of government takedown requests in 2022 compared to 2021.

In addition to requests based on violations of local law, GitHub processed six requests from governments to take down content as a Terms of Service violation, affecting 17 accounts, 15 repositories, and seven GitHub Pages sites in 2022. These requests concerned misinformation (Australia) and GitHub Pages violations (Russia).

Go to our transparency data repo for structured data files of government takedown requests.

DMCA takedowns

How we handle DMCA content removal requests

Consistent with our approach to content moderation across the board, GitHub handles Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) claims to maximize the availability of code by limiting disruption for legitimate projects. Accordingly, we designed our DMCA Takedown Policy to safeguard developer interests against overreaching and ambiguous takedown requests. Most content removal requests we receive are submitted under the DMCA, which allows copyright holders to ask GitHub to take down content they believe infringes on their copyright. If the user who posted the allegedly infringing content believes the takedown was a mistake or misidentification, they can then send a counter notice asking GitHub to reinstate the content.

Additionally, before processing a valid takedown notice that alleges that only part of a repository is infringing, or if we see that’s the case, we give users a chance to address the claims identified in the notice first. We now do this with all valid notices alleging circumvention of a technical protection measure. That way, if the user removes or remediates the specific content identified in the notice, we avoid having to disable any content at all. This is an important element of our DMCA policy, given how much users rely on each other’s code for their projects.

Each time we receive a valid DMCA takedown notice, we redact personal information, as well as any reported URLs where we were unable to determine there was a violation. We then post the notice to a public DMCA repository.

Our DMCA Takedown Policy explains more about the DMCA process, as well as the differences between takedown notices and counter notices. It also sets out the requirements for making a valid request, which include that the person submitting the notice takes into account fair use.

Go to our transparency data repo for structured data files of DMCA takedown notices.

Takedown notices received and processed

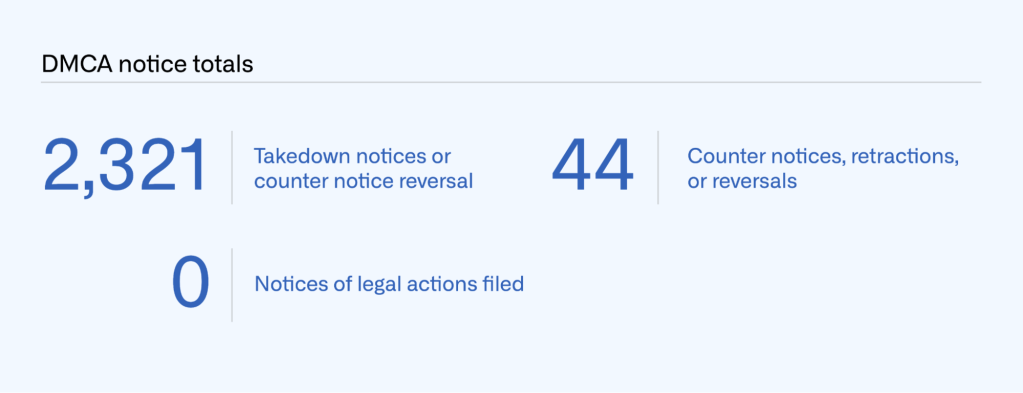

In 2022, GitHub received and processed 2,321 valid DMCA takedown notices. This is the number of separate notices for which we took down content or asked our users to remove content. In addition, we received and processed 36 valid counter notices, one reversal, and seven retractions, for a total of 44 notices that resulted in content being restored in 2022. We did not receive notice of any legal action filed related to a DMCA takedown request during this reporting period.

While content can be taken down, it can also be restored. In some cases, we reinstate content that was taken down if we receive one of the following:

- Counter notice: the person whose content was removed sends us sufficient information to allege that the takedown was the result of a mistake or misidentification.

- Retraction: the person who filed the takedown changes their mind and requests to withdraw it.

- Reversal: after receiving a seemingly complete takedown request, GitHub later receives information that invalidates it, and we reverse our original decision to honor the takedown notice.

These definitions of “retraction” and “reversal” each refer to a takedown request. However, the same can happen with respect to a counter notice.

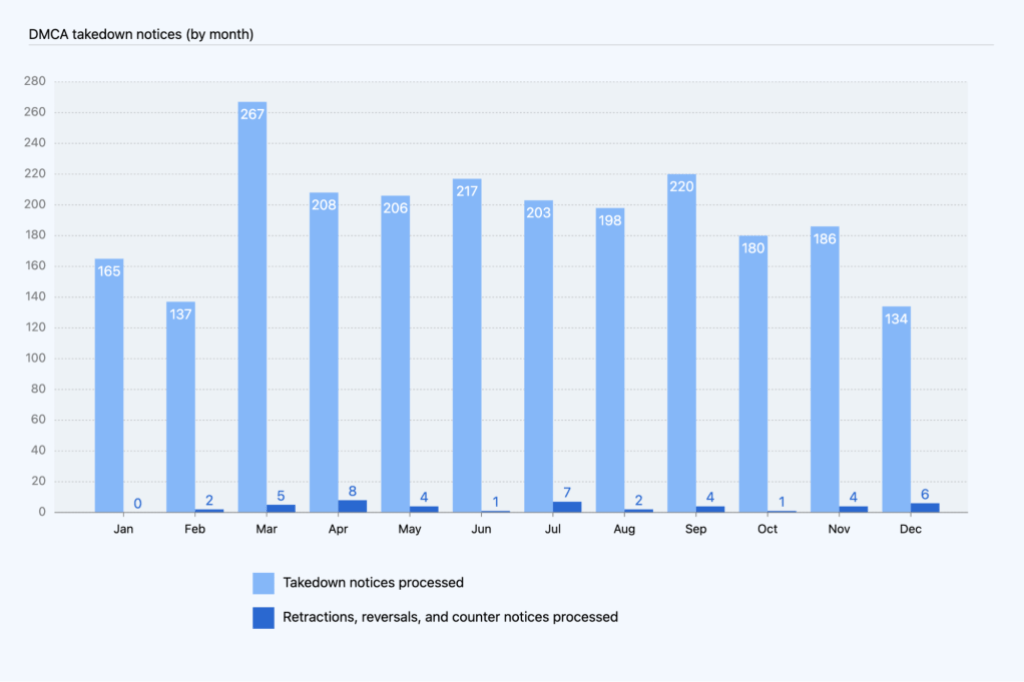

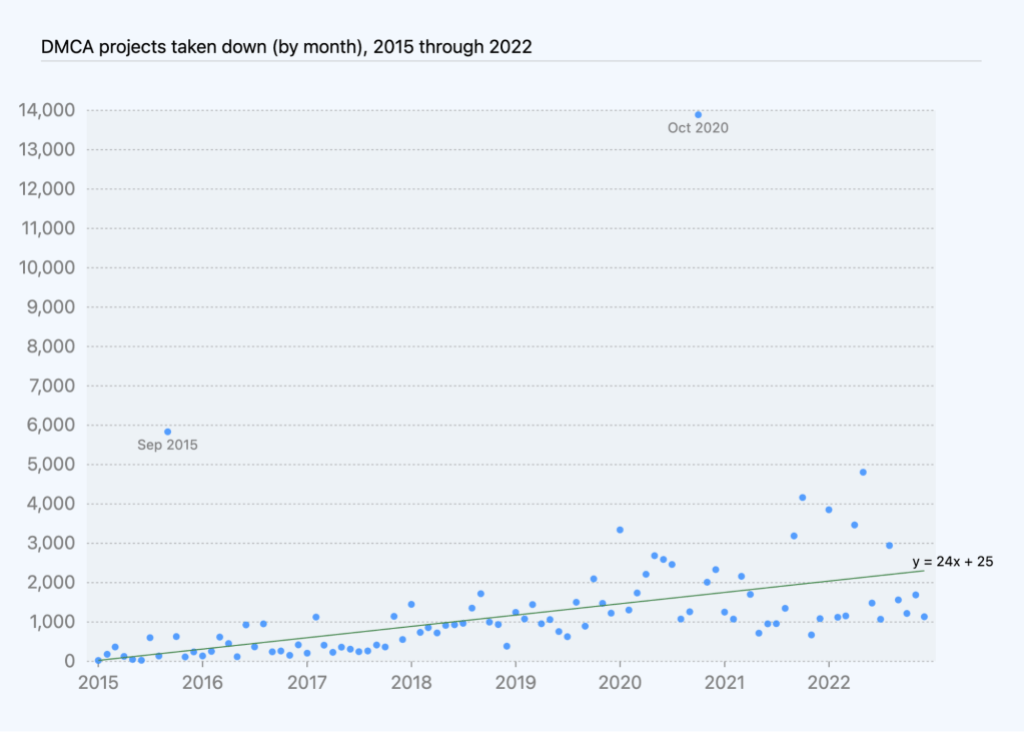

In 2022, the total number of takedown notices ranged from 134 to 267 per month. The monthly totals for counter notices, retractions, and reversals combined ranged from zero to eight.

Projects affected by DMCA takedown requests

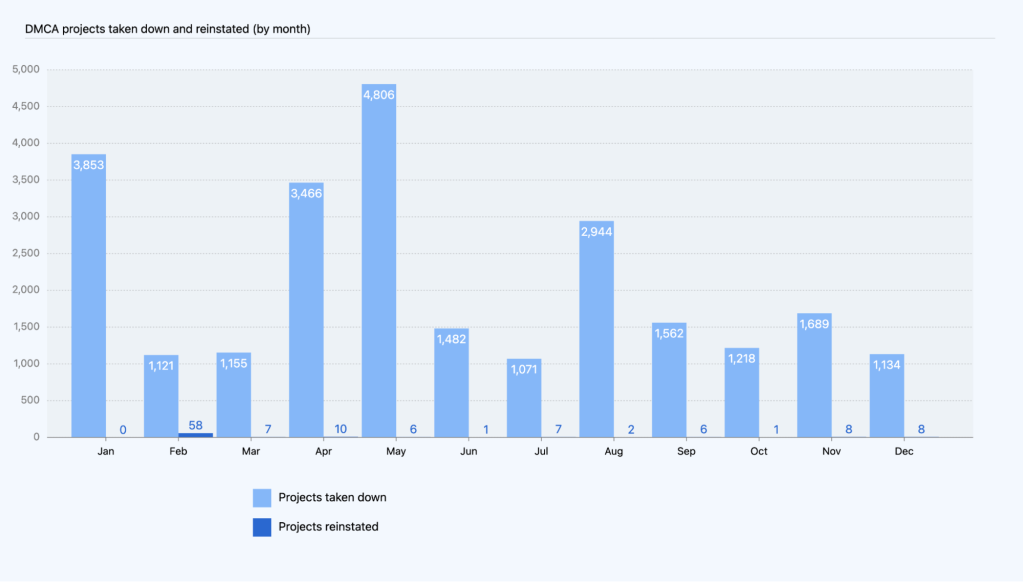

Often, a single takedown notice can encompass more than one project. In these instances, we looked at the total number of projects, including repositories, gists, and GitHub Pages sites that we had taken down due to DMCA takedown requests in 2022.

The monthly totals for projects reinstated—based on a counter notice, retraction, or reversal—ranged from zero to 58. The number of counter notices, retractions, and reversals we receive ranges from less than one to more than five percent of the DMCA-related notices we get each month. This means that most of the time when we receive a valid takedown notice, the content comes down and stays down. In total in 2022, we took down 25,501 projects and reinstated 114, which means that 25,387 projects stayed down.

The number 25,387 may sound like a lot of projects, but it’s less than .02% of the more than 200 million repositories on GitHub in 2022.

That number also includes many projects that are actually currently up. When a user makes changes in response to a takedown notice, we count that in the “stayed down” number. Because the reported content stayed down, we include it even if the rest of the project is still up. Those projects are in addition to the number reinstated.

Circumvention claims

Within our DMCA reporting, we also look specifically at takedown notices that allege circumvention of a technological protection measure under section 1201 of the DMCA. GitHub requires additional information for a DMCA takedown notice to be complete and actionable where it alleges circumvention. Our DMCA Takedown Policy includes a section that specifically addresses circumvention claims and outlines our policy with respect to how we review and process such claims.

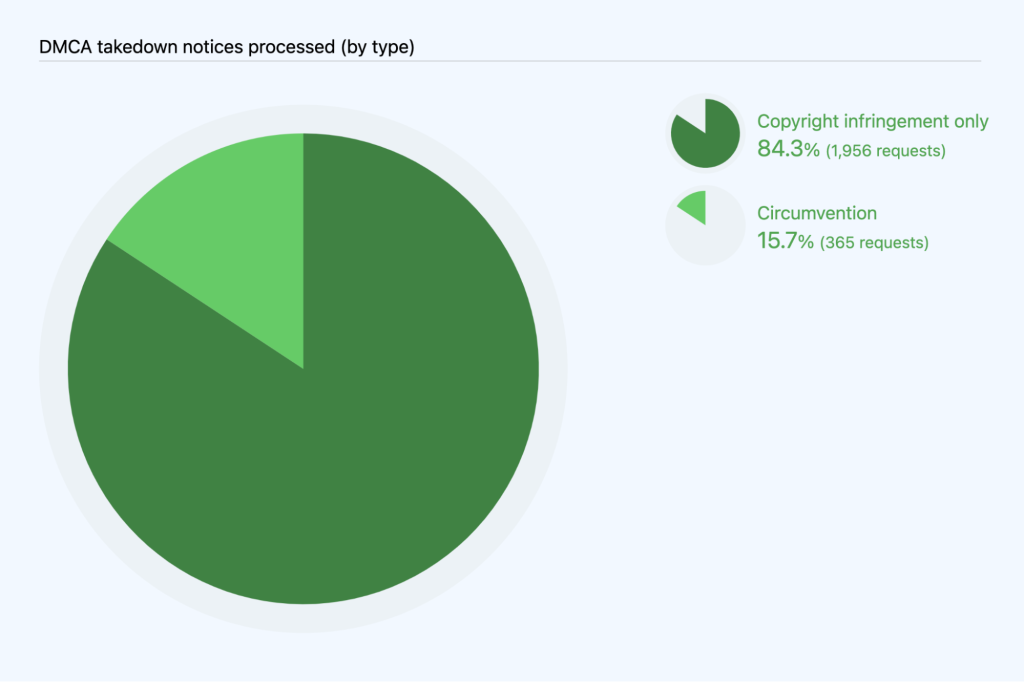

We are able to estimate the number of DMCA notices we processed that include a circumvention claim by searching the takedown notices we processed for relevant keywords. On that basis, we can estimate that of the 2,321 notices we processed in 2022, 365 notices, or 15.7%%, related to circumvention. The proportion of takedown notices that allege circumvention increased significantly in 2022 compared to 2021:

- 365 or 15.7% of all notices in 2022

- 92 or 5% of all notices in 2021

- 63 or 3% of all notices in 2020

- 49 or 2.78% of all notices in 2019

- 33 or 1.83% of notices in 2018

- 25 or 1.81% of notices in 2017

- 36 or 4.74% of notices in 2016

- 18 or 3.56% of notices in 2015

We’re working on an in-depth exploration of what led to this uptick in circumvention claims. Stay tuned for that, and in the meantime, we encourage curious readers to explore our DMCA repository, possibly using a Codespace pre-configured with Jupyter and other data analysis tools.

Incomplete DMCA takedown notices received

The previous DMCA numbers related to valid notices we received. We also received many incomplete or insufficient notices regarding copyright infringement. Because these notices do not result in content removal, we do not currently keep track of how many incomplete notices we receive, or how often our users are able to resolve their issues without sending a takedown notice.

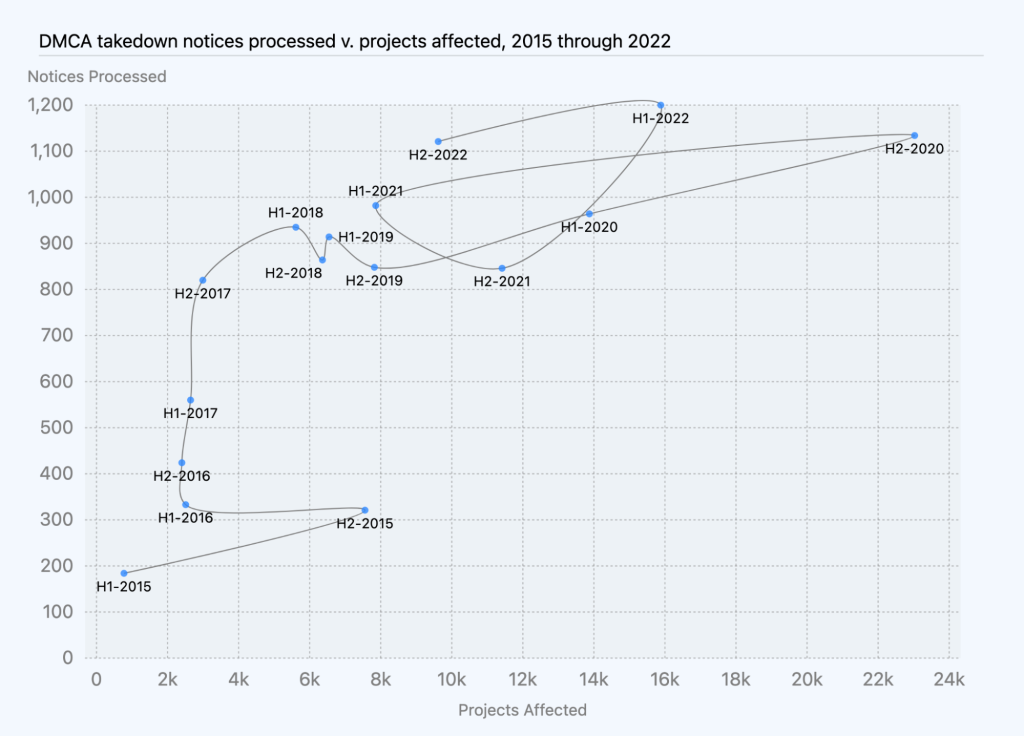

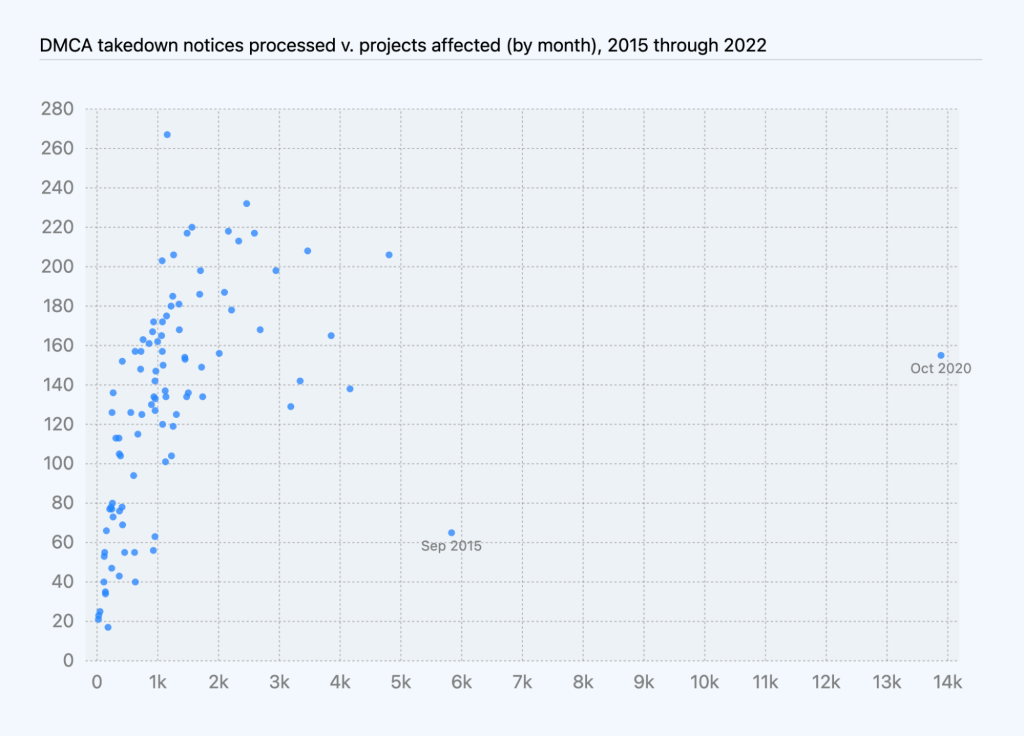

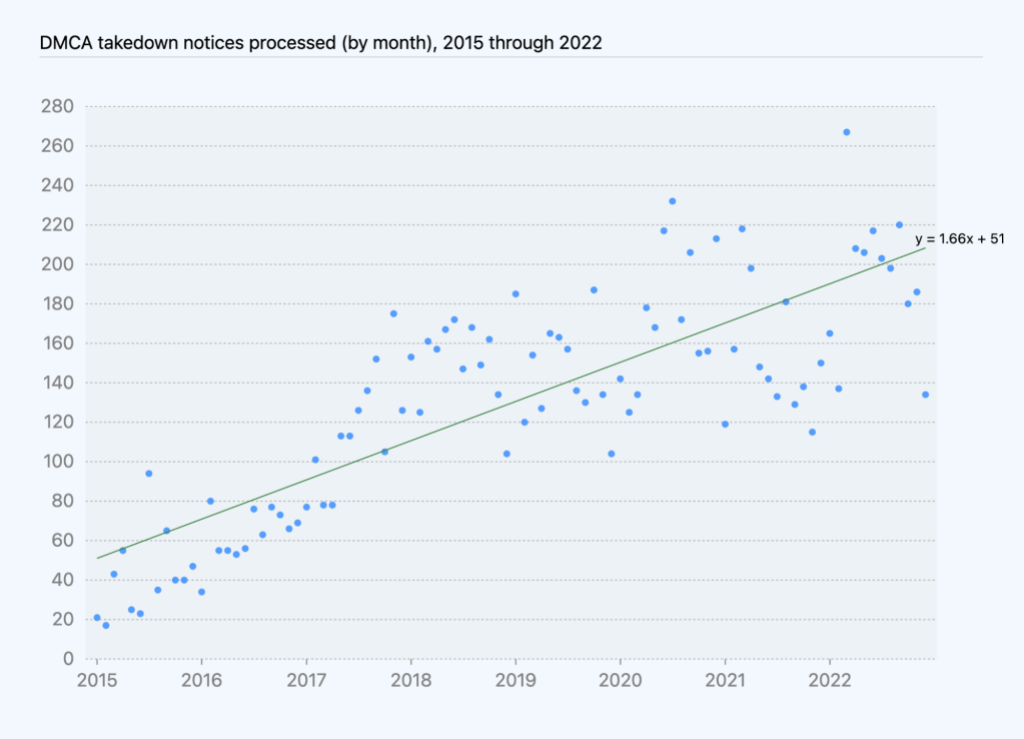

Trends in DMCA data

Based on DMCA data we’ve compiled over the last few years, the number of DMCA notices we received and processed has generally correlated with growth in repositories over the same period of time. In 2022, we saw this trend continue: we processed more DMCA notices than we did in 2021, and those notices affected more projects than in 2021.

The number of takedown notices processed per month shows an increase of roughly 1.7 notices per month, on average, while the number of projects taken down shows an increase of 24 projects affected per month, on average, excluding youtube-dl and one other outlier.

Automated detection

We use automated scanning to detect some of the most egregious kinds of abuse on the platform: child sexual exploitation and abuse imagery (CSEAI) and terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC). We scan based on robust hash matching techniques using the PhotoDNA tool. Our process also involves human review to confirm an image that is initially detected as a hit, and allows users to appeal an automated content moderation decision against them.

In 2022, out of millions of images scanned, we confirmed automated detection of one account with CSEAI, which was reported to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). None of the images scanned contained TVEC. While the data shows very little of this content on the platform, we feel it is important to allocate resources to detect it to safeguard survivors and the community. It is also important to note this data does not include other staff action taken in response to reports of CSEAI or TVEC. We made six additional CSEAI reports to NCMEC based on these cases in 2022.

Appeals and other reinstatements

Reinstatements, including as a result of appeals, are a key component of fairness to our users and respect for their right to a remedy for content removal or account restrictions. Reinstatements can occur when we undo an action we had taken to disable a repository, hide an account, or suspend a user’s access to their account in response to a Terms of Service violation. While sometimes this happens because a user disputes a decision to restrict access to their content (an appeal), in many cases, we reinstate an account after a user removes content that violated our Terms of Service and agrees not to violate them going forward. For the purposes of this report, we looked at reinstatements related to:

- Abuse: violations of our Acceptable Use Policies, except for spam, phishing, and malware

- Trade controls: violations of trade sanctions restrictions

Go to our transparency data repo for structured data files of appeals and other reinstatements.

Abuse-related violations

How we handle abuse-related violations

As explained above, GitHub’s Terms of Service include numerous abuse-related restrictions on content and conduct. There are a number of enforcement actions we can take when we determine a violation of our Terms of Service has occurred. In keeping with our approach of restricting content in the narrowest way possible to address the violation, sometimes we can resolve an issue by disabling one repository (taking down one project) rather than acting on an entire account. Other times, we may need to act at the account level, for example, if the same user is committing the same violation across several repositories.

At the account level, in some cases we will only need to hide a user’s account content—for example, when the violation is based on content being publicly posted—while still giving the user the ability to access their account. In other cases, we will only need to restrict a user’s access to their account—for example, when the violation is based on their interaction with other users—while still giving other users the ability to access their shared content. For a collaborative software development platform like GitHub, we realized we need to provide this option so that other users can still access content that may provide value to their projects.

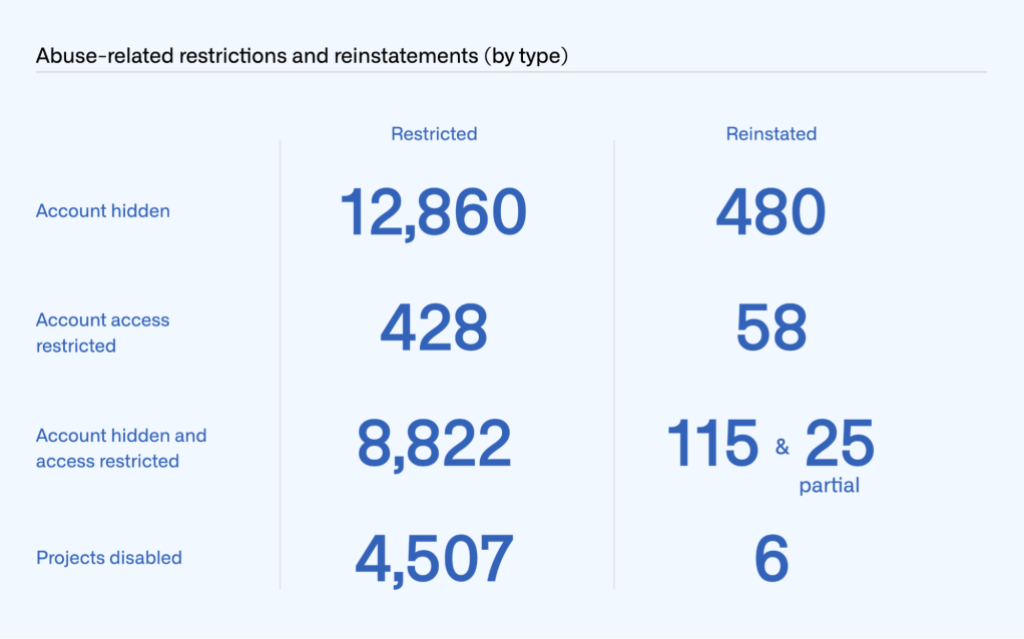

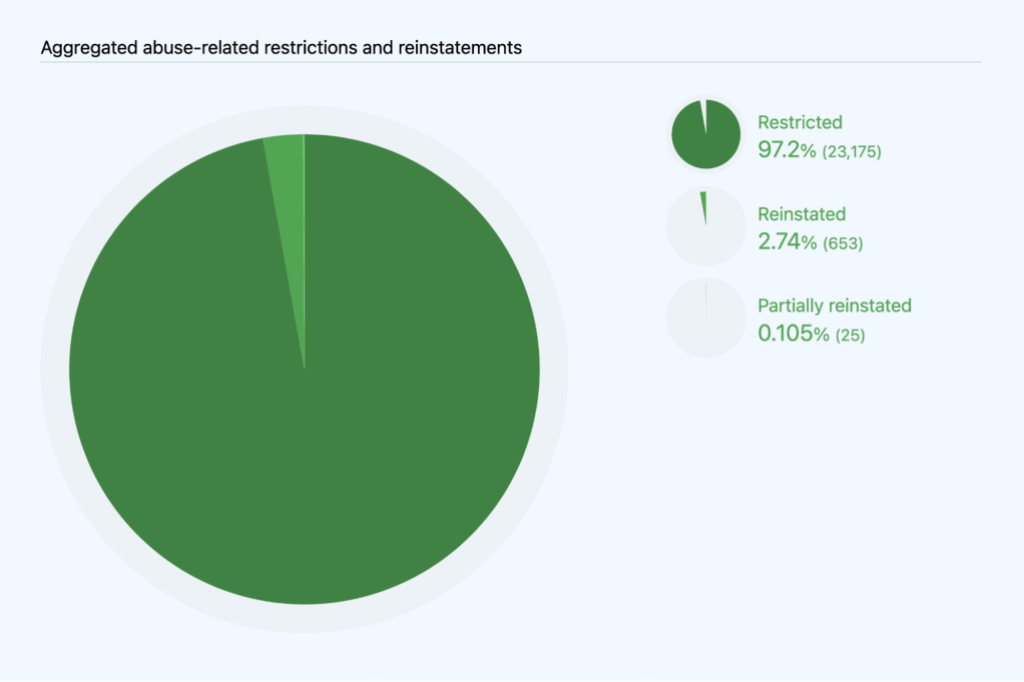

We report on restrictions and reinstatements by type of action taken. In 2022, we hid 12,860 accounts and reinstated 480 hidden accounts. We restricted a repository owner’s access to 428 accounts and reinstated it for 58 accounts. For 8,822accounts, we both hid and restricted the repository owner’s access, lifting both of those restrictions to fully reinstate 115 accounts and partially reinstating 25 accounts. As for abuse-related restrictions at the project level, we disabled 4,507 projects and reinstated six. These do not count DMCA related takedowns or reinstatements (for example, due to counter notices), which are reported on in the DMCA section (above).

Trade controls compliance

We’re dedicated to empowering as many developers around the world as possible to collaborate on GitHub. The US government has imposed sanctions on several countries and regions (Crimea, separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, and Syria), which means GitHub isn’t fully available in some of those places. However, GitHub will continue advocating to US regulators for the greatest possible access to code collaboration services for developers in sanctioned regions. For example, in January 2021 we secured a license from the US government to make all GitHub services fully available to developers in Iran. We are continuing to work toward a similar outcome for developers in Crimea and Syria. Our services are also generally available to developers located in Cuba, aside from specially designated nationals, other denied or blocked parties under US and other applicable law, and certain government officials.

Although trade control laws require GitHub to restrict account access from certain regions, we enable users to appeal these restrictions, and we work with them to restore as many accounts as we legally can. In many cases, we can reinstate a user’s account (grant an appeal), for example after they returned from temporarily traveling to a restricted region or if their account was flagged in error. More information on GitHub and trade controls can be found here.

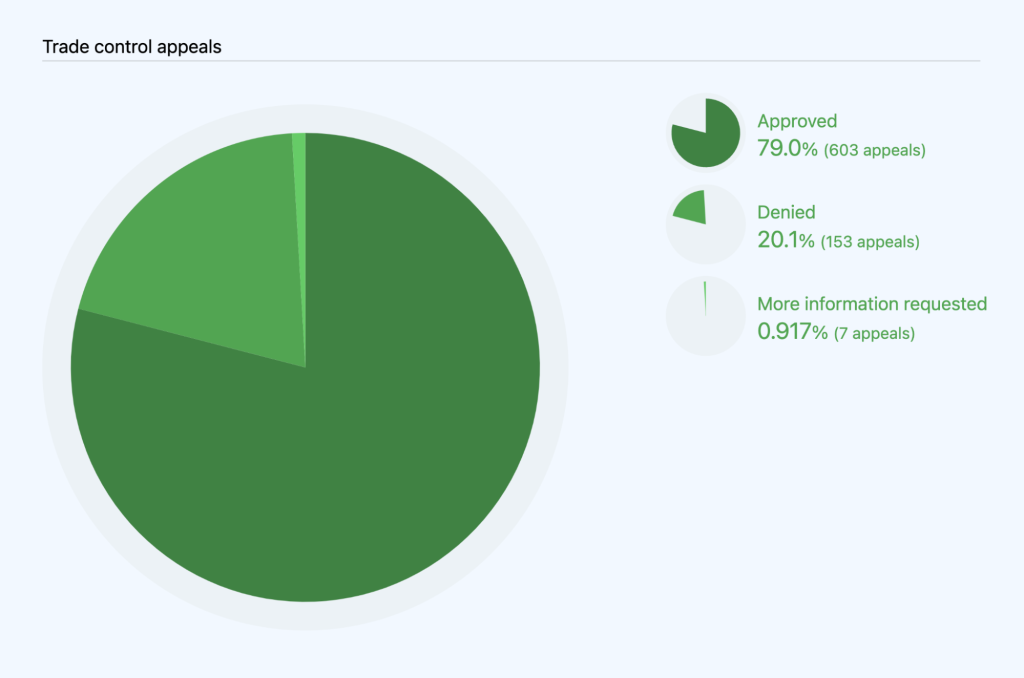

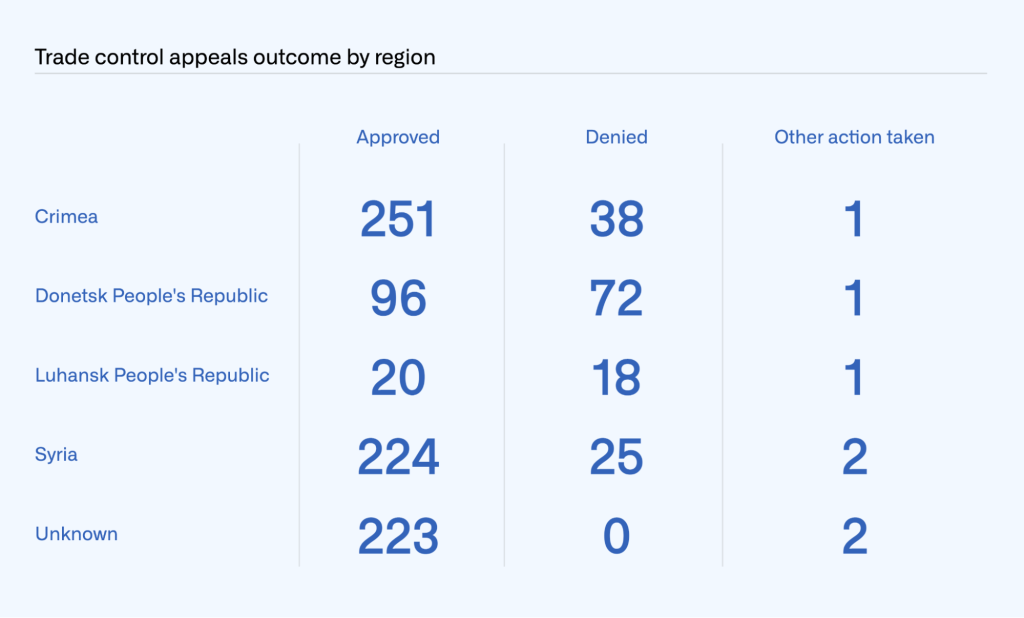

Unlike abuse-related appeals, we must always act at the account level (as opposed to being able to disable a repository) because trade control laws require us to restrict a user’s access to GitHub. In 2022, 763 users appealed trade-control related account restrictions, as compared to 1,504 in 2021. Of the 763 appeals we received in 2022, we approved 603 and denied 153, and required further information to process in seven cases. We also received 212 appeals that were mistakenly filed by users who were not subject to trade controls, so we excluded these from our analysis below.

Appeals varied widely by region in 2022, ranging from 253 related to Crimea to 20 related to the Luhansk People’s Republic. In 223 cases, we were unable to assign an appeal to a region in our data. We marked them as “Unknown” in the table below.

Average monthly active users for EU

In accordance with the Digital Services Act, going forward GitHub will publish information semi-annually on its average monthly active users in the European Union, calculated over a six-month period. For the six-month period of August 2022 through January 2023, GitHub had approximately 10-11 million average monthly active users.

Go to our transparency data repo for structured data files of EU average monthly active users.

Conclusion

Maintaining transparency and promoting free expression are an essential part of our commitment to developers. We aim to lead by example in our approach to transparency by providing in-depth explanation of the areas of content removal that are most relevant to developers and software development platforms. Central to this commitment is protecting user privacy, free association, assembly, and expression by limiting the amount of user data we disclose, and the amount of legitimate content we take down, within the bounds of the law. Through our transparency reports, we shed light on our own practices, while joining in a broader discourse on platform governance. We look forward to finding even more opportunities to expand our transparency reporting in the future.

We hope you found this report helpful and encourage you to let us know if you have suggestions for additions to future reports. For more on how we develop GitHub’s policies and procedures, check out our site policy repository.

Tags:

Written by

Related posts

GitHub availability report: January 2026

In January, we experienced two incidents that resulted in degraded performance across GitHub services.

Pick your agent: Use Claude and Codex on Agent HQ

Claude by Anthropic and OpenAI Codex are now available in public preview on GitHub and VS Code with a Copilot Pro+ or Copilot Enterprise subscription. Here’s what you need to know and how to get started today.

What the fastest-growing tools reveal about how software is being built

What languages are growing fastest, and why? What about the projects that people are interested in the most? Where are new developers cutting their teeth? Let’s take a look at Octoverse data to find out.