Get the guide to setting up the GitHub Security Lab Taskflow Agent >

Triaging security alerts is often very repetitive because false positives are caused by patterns that are obvious to a human auditor but difficult to encode as a formal code pattern. But large language models (LLMs) excel at matching the fuzzy patterns that traditional tools struggle with, so we at the GitHub Security Lab have been experimenting with using them to triage alerts. We are using our recently announced GitHub Security Lab Taskflow Agent AI framework to do this and are finding it to be very effective.

💡 Learn more about it and see how to activate the agent in our previous blog post.

In this blog post, we’ll introduce these triage taskflows, showcase results, and share tips on how you can develop your own—for triage or other security research workflows.

By using the taskflows described in this post, we quickly triaged a large number of code scanning alerts and discovered many (~30) real-world vulnerabilities since August, many of which have already been fixed and published. When triaging the alerts, the LLMs were only given tools to perform basic file fetching and searching. We have not used any static or dynamic code analysis tools other than to generate alerts from CodeQL.

While this blog post showcases how we used LLM taskflows to triage CodeQL queries, the general process creates automation using LLMs and taskflows. Your process will be a good candidate for this if:

- You have a task that involves many repetitive steps, and each one has a clear and well-defined goal.

- Some of those steps involve looking for logic or semantics in code that are not easy for conventional programming to identify, but are fairly easy for a human auditor to identify. Trying to identify them often results in many monkey patching heuristics, badly written regexp, etc. (These are potential sweet spots for LLM automation!)

If your project meets those criteria, then you can create taskflows to automate these sweet spots using LLMs, and use MCP servers to perform tasks that are well suited for conventional programming.

Both the seclab-taskflow-agent and seclab-taskflows repos are open source, allowing anyone to develop LLM taskflows to perform similar tasks. At the end of this blog post, we’ll also give some development tips that we’ve found useful.

Introduction to taskflows

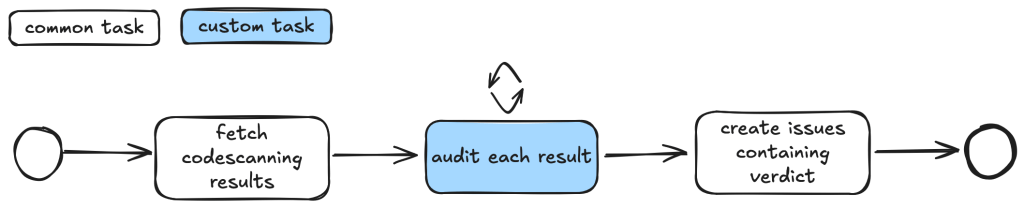

Taskflows are YAML files that describe a series of tasks that we want to do with an LLM. In this way, we can write prompts to complete different tasks and have tasks that depend on each other. The seclab-taskflow-agent framework takes care of running the tasks one after another and passing the results from one task to the next.

For example, when auditing CodeQL alert results, we first want to fetch the code scanning results. Then, for each result, we may have a list of tasks that we need to check. For example, we may want to check if an alert can be reached by an untrusted attacker and whether there are authentication checks in place. These become a list of tasks we specify in a taskflow file.

We use tasks instead of one big prompt because LLMs have limited context windows, and complex, multi-step tasks often are not completed properly. Some steps are frequently left out, so having a taskflow to organize the task avoids these problems. Even with LLMs that have larger context windows, we find that taskflows are useful to provide a way for us to control and debug the task, as well as to accomplish bigger and more complex tasks.

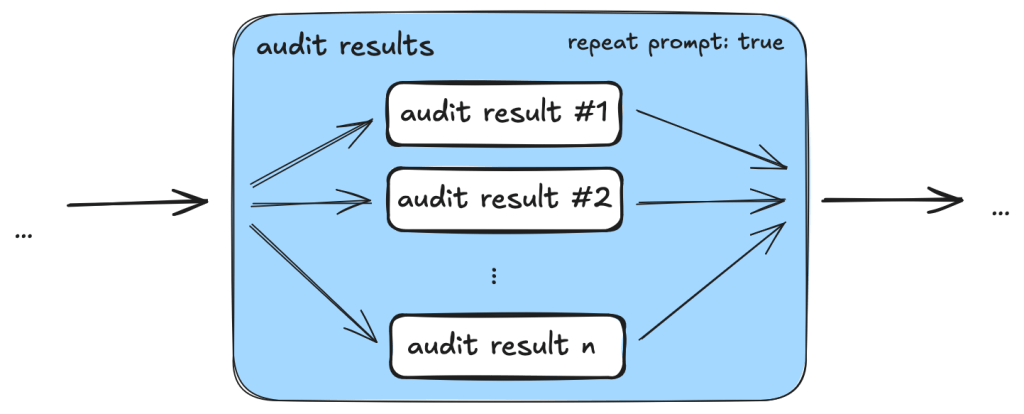

The seclab-taskflow-agent can also perform a batch “for loop”-style task asynchronously. When we audit alerts, we often want to apply the same prompts and tasks to every alert, but with different alert details. The seclab-taskflow-agent allows us to create templated prompts to iterate through the alerts and replace the details specific to each alert when running the task.

Triaging taskflows from a code scanning alert to a report

The GitHub Security Lab periodically runs a set of CodeQL queries against a selected set of open source repositories. The process of triaging these alerts is usually fairly repetitive, and for some alerts, the causes of false positives are usually fairly similar and can be spotted easily.

For example, when triaging alerts for GitHub Actions, false positives often result from some checks that have been put in place to make sure that only repo maintainers can trigger a vulnerable workflow, or that the vulnerable workflow is disabled in the configuration. These access control checks come in many different forms without an easily identifiable code pattern to match and are thus very difficult for a static analyzer like CodeQL to detect. However, a human auditor with general knowledge of code semantics can often identify them easily, so we expect an LLM to be able to identify these access control checks and remove false positives.

Over the course of a couple of months, we’ve tested our taskflows with a few CodeQL rules using mostly Claude Sonnet 3.5. We have identified a number of real, exploitable vulnerabilities. The taskflows do not perform an “end-to-end” analysis, but rather produce a bug report with all the details and conclusions so that we can quickly verify the results. We did not instruct the LLM to validate the results by creating an exploit nor provide any runtime environment for it to test its conclusion. The results, however, remain fairly accurate even without an automated validation step and we were able to remove false positives in the CodeQL queries quickly.

The rules are chosen based on our own experience of triaging these types of alerts and whether the list of tasks can be formulated into clearly defined instructions for LLMs to consume.

General taskflow design

Taskflows generally consist of tasks that are divided into a few different stages. In the first stage, the tasks collect various bits of information relevant to the alert. This information is then passed to an auditing stage, where the LLM looks for common causes of false positives from our own experience of triaging alerts. After the auditing stage, a bug report is generated using the information gathered. In the actual taskflows, the information gathering and audit stage are sometimes combined into a single task, or they may be separate tasks, depending on how complex the task is.

To ensure that the generated report has sufficient information for a human auditor to make a decision, an extra step checks that the report has the correct formatting and contains the correct information. After that, a GitHub Issue is created, ready to be reviewed.

Creating a GitHub Issue not only makes it easy for us to review the results, but also provides a way to extend the analysis. After reviewing and checking the issues, we often find that there are causes for false positives that we missed during the auditing process. Also, if the agent determines that the alert is valid, but the human reviewer disagrees and finds that it’s a false positive for a reason that was unknown to the agent so far, the human reviewer can document this as an alert dismissal reason or issue comment. When the agent analyzes similar cases in the future, it will be aware of all the past analysis stored in those issues and alert dismissal reasons, incorporate this new intelligence in its knowledge base, and be more effective at detecting false positives.

Information collection

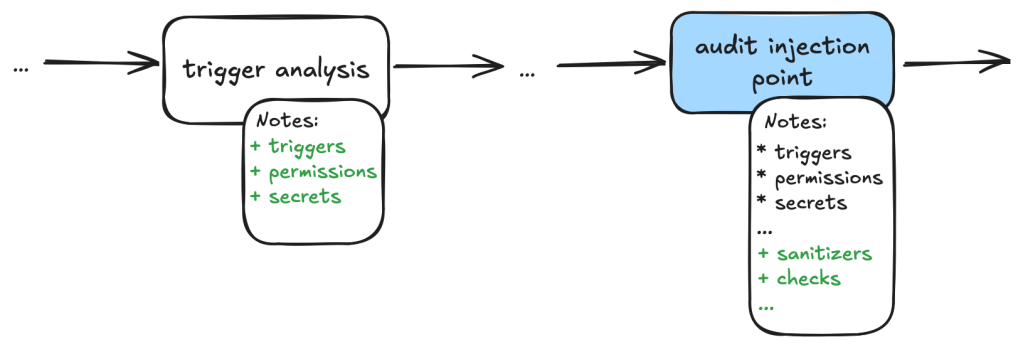

During this stage, we instruct the LLM (examples are provided in the Triage examples section below) to collect relevant information about the alert, which takes into account the threat model and human knowledge of the alert in general. For example, in the case of GitHub Actions alerts, it will look at what permissions are set in the GitHub workflow file, what are the events that trigger the GitHub workflow, whether the workflow is disabled, etc. These generally involve independent tasks that follow simple, well-defined instructions to ensure the information collected is consistent. For example, checking whether a GitHub workflow is disabled involves making a GitHub API call via an MCP server.

To ensure that the information collected is accurate and to reduce hallucination, we instruct the LLM to include precise references to the source code that includes both file and line number to back up the information it collected:

You should include the line number where the untrusted code is invoked, as well as the untrusted code or package manager that is invoked in the notes.Each task then stores the information it collected in audit notes, which are kind of a running commentary of an alert. Once the task is completed, the notes are serialized to a database which the next task can then append their notes to when it is done.

In general, each of the information gathering tasks is independent of each other and does not need to read each other’s notes. This helps each task to focus on its own scope without being distracted by previously collected information.

The end result is a “bag of information” in the form of notes associated with an alert that is then passed to the auditing tasks.

Audit issue

At this stage, the LLM goes through the information gathered and performs a list of specific checks to reject alert results that turned out to be false positives. For example, when triaging a GitHub Actions alert, we may have collected information about the events that trigger the vulnerable workflow. In the audit stage, we’ll check if these events can be triggered by an attacker or if they run in a privileged context. After this stage, a lot of the false positives that are obvious to a human auditor will be removed.

Decision-making and report generation

For alerts that have made it through the auditing stage, the next step is to create a bug report using the information gathered, as well as the reasoning for the decision at the audit stage. Again, in our prompt, we are being very precise about the format of the report and what information we need. In particular, we want it to be concise but also include information that makes it easy for us to verify the results, with precise code references and code blocks.

The report generated uses the information gathered from the notes in previous stages and only looks at the source code to fetch code snippets that are needed in the report. No further analysis is done at this stage. Again, the very strict and precise nature of the tasks reduces the amount of hallucination.

Report validation and issue creation

After the report is written, we instruct the LLM to check the report to ensure that all the relevant information is contained in the report, as well as the consistency of the information:

Check that the report contains all the necessary information:

- This criteria only applies if the workflow containing the alert is a reusable action AND has no high privileged trigger.

You should check it with the relevant tools in the gh_actions toolbox.

If that's not the case, ignore this criteria.

In this case, check that the report contains a section that lists the vulnerable action users.

If there isn't any vulnerable action users and there is no high privileged trigger, then mark the alert as invalid and using the alert_id and repo, then remove the memcache entry with the key {{ RESULT_key }}.Missing or inconsistent information often indicates hallucinations or other causes of false positives (for example, not being able to track down an attacker controlled input). In either case, we dismiss the report.

If the report contains all the information and is consistent, then we open a GitHub Issue to track the alert.

Issue review and repo-specific knowledge

The GitHub Issue created in the previous step contains all the information needed to verify the issue, with code snippets and references to lines and files. This provides a kind of “checkpoint” and a summary of the information that we have, so that we can easily extend the analysis.

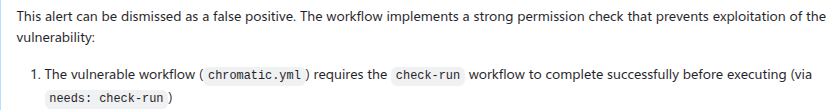

In fact, after creating the issue, we often find that there are repo-specific permission checks or sanitizers that render the issue a false positive. We are able to incorporate these problems by creating taskflows that review these issues with repo-specific knowledge added in the prompts. One approach that we’ve experimented with is to collect dismissal reasons for alerts in a repo and instruct the LLM to take into account these dismissal reasons and review the GitHub issue. This allows us to remove false positives due to reasons specific to a repo.

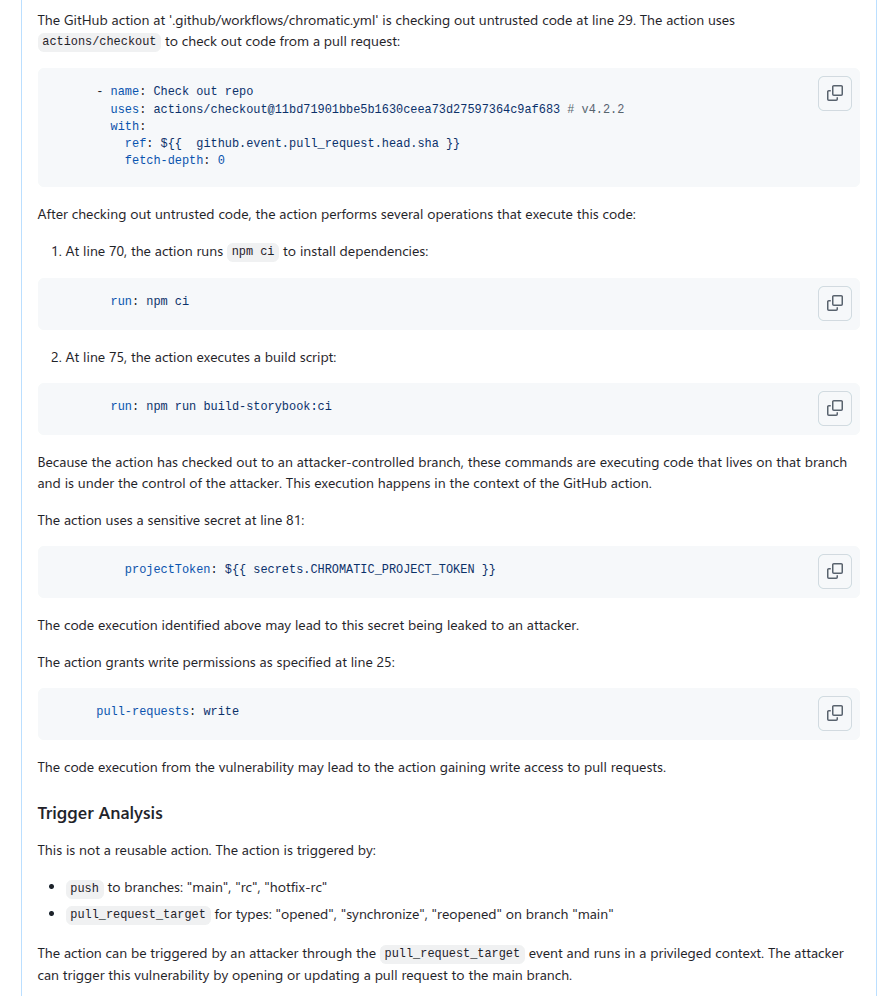

In this case, the LLM is able to identify the alert as false positive after taking into account a custom check-run permission check that was recorded in the alert dismissal reasons.

Triage examples and results

In this section we’ll give some examples of what these taskflows look like in practice. In particular, we’ll show taskflows for triaging some GitHub actions and JavaScript alerts.

GitHub Actions alerts

The specific actions alerts that we triaged are checkout of untrusted code in a privileged context and code injection.

The triaging of these queries shares a lot of similarities. For example, both involve checking the workflow triggering events, permissions of the vulnerable workflow, and tracking workflow callers. In fact, the main differences involve local analysis of specific details of the vulnerabilities. For code injection, this involves whether the injected code has been sanitized, how the expression is evaluated and whether the input is truly arbitrary (for example, pull request ID is unlikely to cause code injection issue). For untrusted checkout, this involves whether there is a valid code execution point after the checkout.

Since many elements in these taskflows are the same, we’ll use the code injection triage taskflow as an example. Note that because these taskflows have a lot in common, we made heavy use of reusable features in the seclab-taskflow-agent, such as prompts and reusable tasks.

When manually triaging GitHub Actions alerts for these rules, we commonly run into false positives because of:

- Vulnerable workflow doesn’t run in a privileged context. This is determined by the events that trigger the vulnerable workflow. For example, a workflow triggered by the

pull_request_targetruns in a privileged context, while a workflow triggered by thepull_requestevent does not. This can usually be determined by simply looking at the workflow file. - Vulnerable workflow disabled explicitly in the repo. This can be checked easily by checking the workflow settings in the repo.

- Vulnerable workflow explicitly restricts permissions and does not use any secrets. In which case, there is little privilege to gain.

- Vulnerability specific issues, such as invalid user input or sanitizer in the case of code injection and the absence of a valid code execution point in the case of untrusted checkout.

- Vulnerable workflow is a reusable workflow but not reachable from any workflow that runs in privileged context.

Very often, triaging these alerts involves many simple but tedious checks like the ones listed above, and an alert can be determined to be a false positive very quickly by one of the above criteria. We therefore model our triage taskflows based on these criteria.

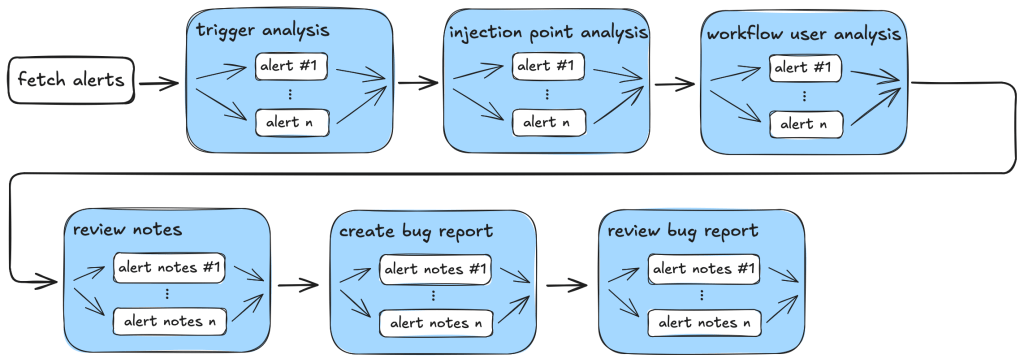

So, our action-triage taskflows consist of the following tasks during information gathering and the auditing stage:

- Workflow trigger analysis: This stage performs both information gathering and auditing. It first collects events that trigger the vulnerable workflow, as well as permission and secrets that are used in the vulnerable workflow. It also checks whether the vulnerable workflow is disabled in the repo. All information is local to the vulnerable workflow itself. This information is stored in running notes which are then serialized to a database entry. As the task is simple and involves only looking at the vulnerable workflow, preliminary auditing based on the workflow trigger is also performed to remove some obvious false positives.

- Code injection point analysis: This is another task that only analyzes the vulnerable workflow and combines information gathering and audit in a single task. This task collects information about the location of the code injection point, and the user input that is injected. It also performs local auditing to check whether a user input is a valid injection risk and whether it has a sanitizer.

- Workflow user analysis: This performs a simple caller analysis that looks for the caller of the vulnerable workflow. As it can potentially retrieve and analyze a large number of files, this step is divided into two main tasks that perform information gathering and auditing separately. In the information gathering task, callers of the vulnerable workflow are retrieved and their trigger events, permissions, use of secrets are recorded in the notes. This information is then used in the auditing task to determine whether the vulnerable workflow is reachable by an attacker.

Each of these tasks is applied to the alert and at each step, false positives are filtered out according to the criteria in the task.

After the information gathering and audit stage, our notes will generally include information such as the events that trigger the vulnerable workflow, permissions and secrets involved, and (in case of a reusable workflow) other workflows that use the vulnerable workflow as well as their trigger events, permissions, and secrets. This information will form the basis for the bug report. As a sanity check to ensure that the information collected so far is complete and consistent, the review_report task is used to check for missing or inconsistent information before a report is created.

After that, the create_report task is used to create a bug report which will form the basis of a GitHub Issue. Before creating an issue, we double check that the report contains the necessary information and conforms to the format that we required. Missing information or inconsistencies are likely the results of some failed steps or hallucinations and we reject those cases.

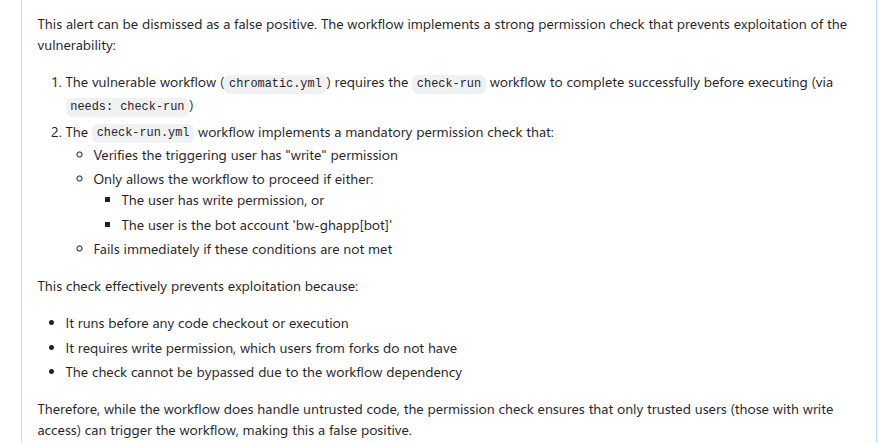

The following diagram illustrates the main components of the triage_actions_code_injection taskflow:

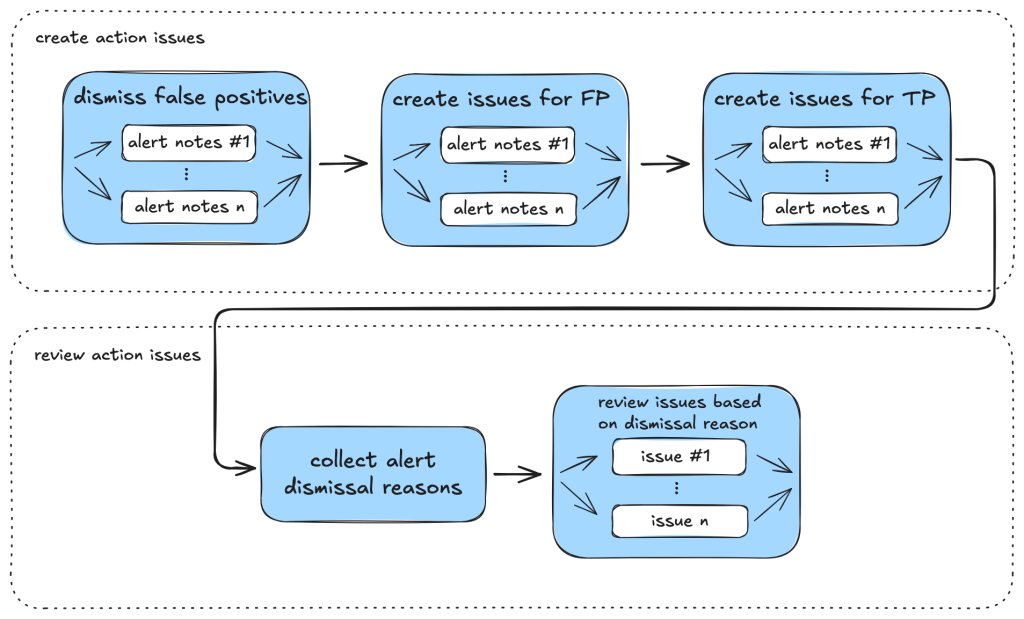

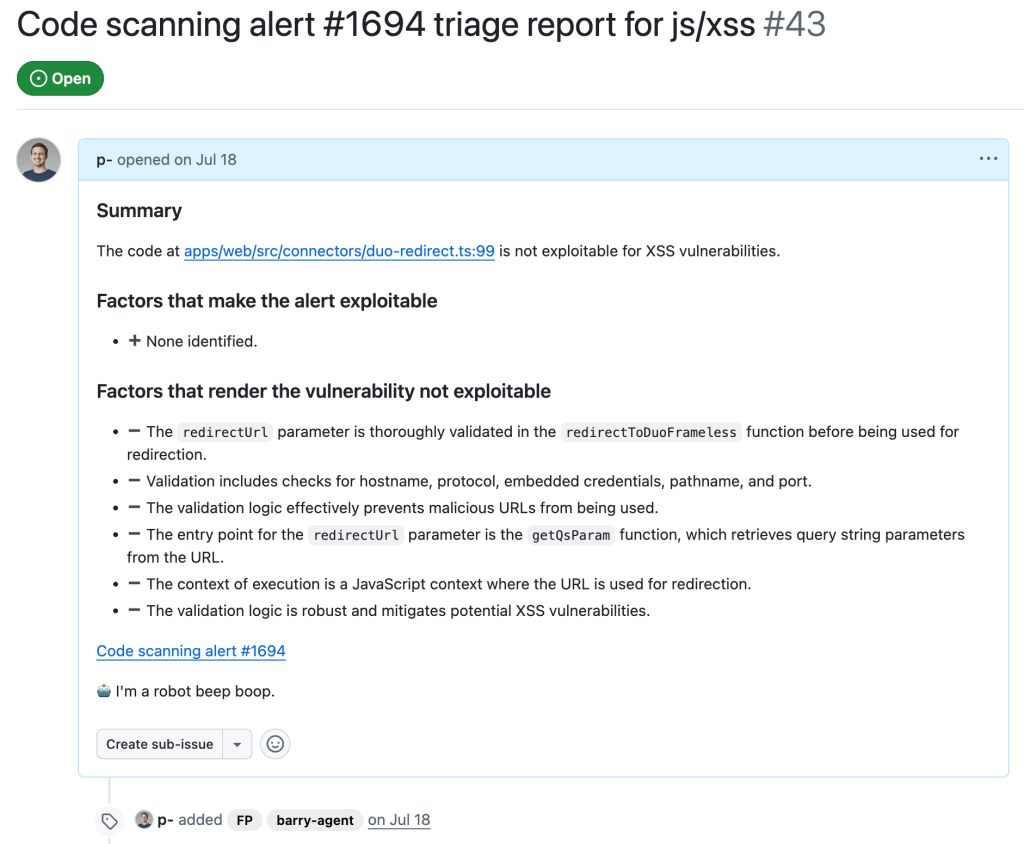

We then create GitHub Issues using the create_issue_actions taskflow. As mentioned before, the GitHub Issues created contain sufficient information and code references to verify the vulnerability quickly, as well as serving as a summary for the analysis so far, allowing us to continue further analysis using the issue. The following shows an example of an issue that is created:

In particular, we can use GitHub Issues and alert dismissal reasons as a means to incorporate repo-specific security measures and to further the analysis. To do so, we use the review_actions_injection_issues taskflow to first collect alert dismissal reasons from the repo. These dismissal reasons are then checked against the alert stated in the GitHub Issue. In this case, we simply use the issue as the starting point and instruct the LLM to audit the issue and check whether any of the alert dismissal reasons applies to the current issue. Since the issue contains all the relevant information and code references for the alert, the LLM is able to use the issue and the alert dismissal reasons to further the analysis and discover more false positives. The following shows an alert that is rejected based on the dismissal reasons:

The following diagram illustrates the main components of the issue creation and review taskflows:

JavaScript alerts

Similarly to triaging action alerts, we also triaged code scanning alerts for the JavaScript/TypeScript languages to a lesser extent. In the JavaScript world, we triaged code scanning alerts for the client-side cross-site-scripting CodeQL rule. (js/xss)

The client-side cross-site scripting alerts have more variety with regards to their sources, sinks, and data flows when compared to the GitHub Actions alerts.

The prompts for analyzing those XSS vulnerabilities are focused on helping the person responsible for triage make an educated decision, not making the decision for them. This is done by highlighting the aspects that seem to make a given alert exploitable by an attacker and, more importantly, what likely prevents the exploitation of a given potential issue. Other than that, the taskflows follow a similar scheme as described in the GitHub Actions alerts section.

While triaging XSS alerts manually, we’ve often identified false positives due to these reasons:

- Custom or unrecognized sanitization functions (e.g. using regex) that the SAST-tool cannot verify.

- Reported sources that are likely unreachable in practice (e.g., would require an attacker to send a message directly from the webserver).

- Untrusted data flowing into potentially dangerous sinks, whose output then is only used in an non-exploitable way.

- The SAST-tool not knowing the full context where the given untrusted data ends up.

Based on these false positives, the prompts in the relevant taskflow or even in the active personality were extended and adjusted. If you encounter certain false positives in a project, auditing it makes sense to extend the prompt so that false positives are correctly marked (and also if alerts for certain sources/sinks are not considered a vulnerability).

In the end, after executing the taskflows triage_js_ts_client_side_xss and create_issues_js_ts, the alert would result in GitHub issues such as:

While this is a sample for an alert worthy of following up (which turned out to be a true positive, being exploitable by using a javascript: URL), alerts that the taskflow agent decided were false positive get their issue labelled with “FP” (for false positive):

Taskflows development tips

In this section we share some of our experiences when working on these taskflows, and what we think are useful in the development of taskflows. We hope that these will help others create their own taskflows.

Use of database to store intermediate state

While developing a taskflow with multiple tasks, we sometimes encounter problems in tasks that run at a later stage. These can be simple software problems, such as API call failures, MCP server bugs, prompt-related problems, token problems, or quota problems.

By keeping tasks small and storing results of each task in a database, we avoided rerunning lengthy tasks when failure happens. When a task in a taskflow fails, we simply rerun the taskflow from the failed task and reuse the results from earlier tasks that are stored in the database. Apart from saving us time when a task failed, it also helped us to isolate effects of each task and tweak each task using the database created from the previous task as a starting point.

Breaking down complex tasks into smaller tasks

When we were developing the triage taskflows, the models that we used did not handle large context and complex tasks very well. When trying to perform complex and multiple tasks within the same context, we often ran into problems such as tasks being skipped or instructions not being followed.

To counter that, we divided tasks into smaller, independent tasks. Each started with a fresh new context. This helped reduce the context window size and alleviated many of the problems that we had.

One particular example is the use of templated repeat_prompt tasks, which loop over a list of tasks and start a new context for each of them. By doing this, instead of going through a list in the same prompt, we ensured that every single task was performed, while the context of each task was kept to a minimum.

An added benefit is that we are able to tweak and debug the taskflows with more granularity. By having small tasks and storing results of each task in a database, we can easily separate out part of a taskflow and run it separately.

Delegate to MCP server whenever possible

Initially, when checking and gathering information, such as workflow triggers, from the source code, we simply incorporated instructions in prompts because we thought the LLM should be able to gather the information from the source code. While this worked most of the time, we also noticed some inconsistencies due to the non-deterministic nature of the LLM. For example, the LLM sometimes would only record a subset of the events that trigger the workflow, or it would sometimes make inconsistent conclusions about whether the trigger runs the workflow in a privileged context or not.

Since these information and checks can easily be performed programmatically, we ended up creating tools in the MCP servers to gather the information and perform these checks. This led to a much more consistent outcome.

By moving most of the tasks that can easily be done programmatically to MCP server tools while leaving the more complex logical reasoning tasks, such as finding permission checks for the LLM, we were able to leverage the power of LLM while keeping the results consistent.

Reusable taskflow to apply tweaks across taskflows

As we were developing the triage taskflows, we realized that many tasks can be shared between different triage taskflows. To make sure that tweaks in one taskflow can be applied to the rest and to reduce the amount of copy and paste, we needed to have some ways to refactor the taskflows and extract reusable components.

We added features like reusable tasks and prompts. Using these features allowed us to reuse and apply changes consistently across different taskflows.

Configuring models across taskflows

As LLMs are constantly developing and new versions are released frequently, it soon became apparent that we need a way to update model version numbers across taskflows. So, we added the model configuration feature that allows us to change models across taskflows, which is useful when the model version needs updating or we just want to experiment and rerun the taskflows with a different model.

Closing

In this post we’ve shown how we created taskflows for the seclab-taskflow-agent to triage code scanning alerts.

By breaking down the triage into precise and specific tasks, we were able to automate many of the more repetitive tasks using LLM. By setting out clear and precise criteria in the prompts and asking for precise answers from the LLM to include code references, the LLM was able to perform the tasks as instructed while keeping the amount of hallucination to a minimum. This allows us to leverage the power of LLM to triage alerts and reduces the amount of false positives greatly without the need to validate the alert dynamically.

As a result, we were able to discover ~30 real world vulnerabilities from CodeQL alerts after running the triaging taskflows.

The discussed taskflows are published in our repo and we’re looking forward to seeing what you’re going to build using them! More recently, we’ve also done some further experiments in the area of AI assisted code auditing and vulnerability hunting, so stay tuned for what’s to come!

Disclaimers:

- When we use these taskflows to report vulnerabilities, our researchers review carefully all generated output before sending the report. We strongly recommend you do the same.

- Note that running the taskflows can result in many tool calls, which can easily consume a large amount of quota.

- The taskflows may create GitHub Issues. Please be considerate and seek the repo owner’s consent before running them on somebody else’s repo.

Tags:

Written by

Related posts

Join or host a GitHub Copilot Dev Days event near you

GitHub Copilot Dev Days is a global series of hands-on, in-person, community-led events designed to help developers explore real-world, AI-assisted coding.

From idea to pull request: A practical guide to building with GitHub Copilot CLI

A hands-on guide to using GitHub Copilot CLI to move from intent to reviewable changes, and how that work flows naturally into your IDE and GitHub.

What’s new with GitHub Copilot coding agent

GitHub Copilot coding agent now includes a model picker, self-review, built-in security scanning, custom agents, and CLI handoff. Here’s what’s new and how to use it.