Network problems last Friday

On Friday, November 30th, GitHub had a rough day. We experienced 18 minutes of complete unavailability along with sporadic bursts of slow responses and intermittent errors for the entire day.…

On Friday, November 30th, GitHub had a rough day. We experienced 18

minutes of complete unavailability along with sporadic bursts of slow

responses and intermittent errors for the entire day. I’m very sorry

this happened and I want to take some time to explain what happened,

how we responded, and what we’re doing to help prevent a similar

problem in the future.

Note: I initially forgot to mention that we had a single fileserver pair offline

for a large part of the day affecting a small percentage of repositories.

This was a side effect of the network problems and their impact on the

high-availability clustering between the fileserver nodes. My apologies

for missing this on the initial writeup.

Background

To understand the problem on Friday, you first need to understand how

our network is constructed. GitHub has grown incredibly quickly over

the past few years. A consequence of that growth is that our infrastructure

has, at times, struggled to keep up with the growth.

Most recently, we’ve been seeing some significant problems with network

performance throughout our network. Actions that should respond in

under a millisecond were taking several times that long with occasional

spikes to hundreds of times that long. Services that we’ve wanted to

roll out have been blocked by scalability concerns and we’ve had a

number of brief outages that have been the result of the network

straining beyond the breaking point.

The most pressing problem was with the way our network switches were

interconnected. Conceptually, each of our switches were connected to

the switches in the neighboring racks. Any data that had to travel from

a server on one end of the network to a server on the other end had to

pass through all of the switches in between. This design often put

a very large strain on the switches in the middle of the chain and those

links became saturated, slowing down any data that had to pass through

them.

To solve this problem, we purchased additional switches to build what’s

called an aggregation network, which is more of a tree structure.

Network switches at the top of the tree (aggregation swtiches) are

directly connected to switches in each server cabinet (access switches).

This topology assures that data never has to move between more than

3 tiers: The switch in the originating cabinet, the aggregation switches,

and the switch in the destination cabinet. This allows the links between

switches to be much more efficiently used.

What went wrong?

Last week the new aggregation switches finally arrived and were installed in

our datacenter. Due to the lack of available ports in our access

switches, we needed to disconnect access switches, change the

configuration to support the aggregation design, and then reconnect them to

the aggregation switches. Fortunately, we’ve built our network with

redundant switches in each server cabinet and each server is

connected to both of these switches. We generally refer to these as “A”

and “B” switches.

Our plan was to perform this operation on the B switches and observe

the behavior before transitioning to the A switches and completing the

migration. On Thursday, November 29th we made these changes on the B

devices and despite a few small hiccups the process went essentially

according to plan. We were initially encouraged by the data we were

collecting and planned to make similar changes to the A switches the

following morning.

On Friday morning, we began making the changes to bring the A switches

into the new network. We moved one device at a time and the maintenance

proceeded exactly as planned until we reached the final switch. As we

connected the final A switch, we lost connectivity with the B switch in

the same cabinet. Investigating further, we discovered a

misconfiguration on this pair of switches that caused what’s called a

“bridge loop” in the

network. The switches are specifically configured to detect this sort

of problem and to protect the network by disabling links where

they detect an issue, and that’s what happened in this case.

We were able to quickly resolve the initial problem and return the

affected B switch to service, completing the migration. Unfortunately,

we were not seeing the performance levels we expected. As we

dug deeper we saw that all of the connections between the access

switches and the aggregation switches were completely

saturated. We initially diagnosed this as a “broadcast

storm” which is one

possible consequence of a bridge loop that goes undetected.

We spent most of the day auditing our switch

configurations again, going through every port trying to locate what

we believed to be a loop. As part of that process we decided to

disconnect individual links between the access and aggregation switches

and observe behavior to see if we could narrow the scope of the problem

further. When we did this, we discovered another problem: The moment we

disconnected one of the access/aggregation links in a redundant pair,

the access switch would disable its redundant link as well. This was

unexpected and meant that we did not have the ability to withstand a

failure of one of our aggregation switches.

We escalated this problem to our switch vendor and worked with them to

identify a misconfiguration. We had a setting that was intended to

detect partial link failure between two links. Essentially it would

monitor to try and ensure that both the transmit and receive functions

were functioning correctly. Unfortunately, this feature is not

supported between the aggregation and access switch models. When we

shut down an individual link, this watchdog process would erroneously

trigger and force all the links to be disabled. The 18 minute period of

hard downtime we had was during this troubleshooting process when we

lost connectivity to multiple switches simultaneously.

Once we removed the misconfigured setting on our access switches we

were able to continue testing links and our failover functioned as

expected. We were able to remove any single switch at either the

aggregation or access layer without impacting the underlying servers.

This allowed us to continue moving through individual links in the hunt

for what we still believed was a loop induced broadcast storm.

After a couple more hours of troubleshooting we were unable to track

down any problems with the configuration and again escalated to our

network vendor. They immediately began troubleshooting the problem with

us and escalated it to their highest severity level. We spent five

hours Friday night troubleshooting the problem and eventually

discovered a bug in the aggregation switches was to blame.

When a network switch receives an ethernet frame, it inspects the

contents of that frame to determine the destination MAC address. It

then looks up the MAC address in an internal MAC address

table to determine which port

the destination device is connected to. If it finds a match for the MAC

address in its table, it forwards the frame to that port. If, however,

it does not have the destination MAC address in its table it is forced

to “flood” that frame to all of its ports with the exception of the

port that it was received from.

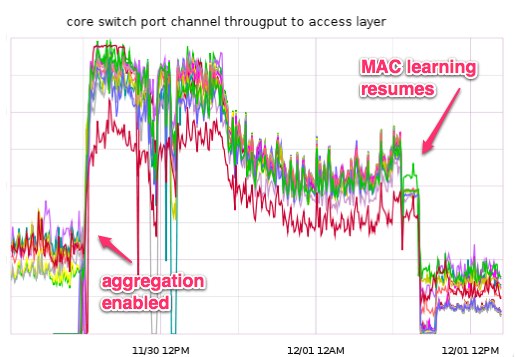

In the course of our troubleshooting we discovered that our aggregation

switches were missing a number of MAC addresses from their tables, and

thus were flooding any traffic that was sent to those devices across

all of their ports. Because of these missing addresses, a large

percentage of our traffic was being sent to every access switch and not

just the switch that the destination devices was connected to. During

normal operation, the switch should “learn” which port each MAC address

is connected through as it processes traffic. For some reason, our

switches were unable to learn a significant percentage of our MAC

addresses and this aggregate traffic was enough to saturate all of the

links between the access and aggregation switches, causing the poor

performance we saw throughout the day.

We worked with the vendor until late on Friday night to formulate a

mitigation plan and to collect data for their engineering team to

review. Once we had a mitigation plan, we scheduled a network

maintenance window on Saturday morning at 0600 Pacific to attempt to

work around the problem. The workaround involved restarting some core

processes on the aggregation switches in order to attempt to allow them

to learn MAC addresses again. This workaround was successful and

traffic and performance returned to normal levels.

Where do we go from here?

- We have worked with our network vendor to provide diagnostic

information which led them to discover the root cause for the MAC

learning issues. We expect a final fix for this issue within the next

week or so and will be deploying a software update to our switches at

that time. In the mean time we are closely monitoring our aggregation

to access layer capacity and have a workaround process if the problem

comes up again. - We designed this maintenance so that it would have no impact on

customers, but we clearly failed. With this in mind, we are

planning to invest in a duplicate of our network stack from our routers

all the way through our access layer switches to be used in a staging

environment. This will allow us to more fully test these kinds of

changes in the future, and hopefully detect bugs like the one that

caused the problems on Friday. - We are working on adding additional automated monitoring to our

network to alert us sooner if we have similar issues. - We need to be more mindful of tunnel-vision during incident

response. We fixated for a very long time on the idea of a bridge loop

and it blinded us to other possible causes. We hope to begin doing more

scheduled incident response exercises in the coming months and will

build scenarios that reinforce this. - The very positive experience we had with our network vendor’s

support staff has caused us to change the way we think

about engaging support. In the future, we will contact their support

team at the first sign of trouble in the network.

Summary

We know you depend on GitHub and we’re going to continue to work hard

to live up to the trust you place in us. Incidents like the one we

experienced on Friday aren’t fun for anyone, but we always strive to

use them as a learning opportunity and a way to improve our craft. We

have many infrastructure improvements planned for the coming year and

the lessons we learned from this outage will only help us as we plan

them.

Finally, I’d like to personally thank the entire GitHub community

for your patience and kind words while we were working through these

problems on Friday.

Written by

Related posts

GitHub availability report: January 2026

In January, we experienced two incidents that resulted in degraded performance across GitHub services.

Pick your agent: Use Claude and Codex on Agent HQ

Claude by Anthropic and OpenAI Codex are now available in public preview on GitHub and VS Code with a Copilot Pro+ or Copilot Enterprise subscription. Here’s what you need to know and how to get started today.

What the fastest-growing tools reveal about how software is being built

What languages are growing fastest, and why? What about the projects that people are interested in the most? Where are new developers cutting their teeth? Let’s take a look at Octoverse data to find out.