At GitHub, we believe that maintaining transparency is an essential part of our commitment to our users. For the past three years we’ve published transparency reports to better inform the public about GitHub’s disclosure of user information and removal of content.

GitHub promotes transparency by:

- Directly engaging our users in developing our policies

- Explaining our reasons for making different policy decisions

- Notifying users when we need to restrict content, with our reasons

- Allowing users to appeal removal of their content

- Publicly posting takedown requests (requests to remove content) in real time in a public repository

We hope our transparency report will interest GitHub users and contribute to broader discourse on platform governance. If you’re unfamiliar with GitHub terminology, please refer to the GitHub Glossary.

In this report, we fill you in on 2017 stats for:

- Requests to disclose user information

- Subpoenas

- Court orders

- Search warrants

- National security orders

- Requests to remove or block user content

- Government takedown requests

- Takedown notices for alleged copyright infringement under the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

New in 2017 are:

- Cross-border data requests

- Accounts and projects affected by government takedown requests

GitHub’s Guidelines for Legal Requests of User Data explain how we handle legally authorized requests, including law enforcement requests, subpoenas, court orders, search warrants, and national security orders.

A subpoena (a written order to compel someone to testify on a particular subject) does not require review by a judge or magistrate. By contrast, a search warrant or court order does require judicial review.

As we note in our guidelines:

- We only release information to third-parties when the appropriate legal requirements have been satisfied

- We require a subpoena to disclose certain kinds of user information, like a name, an email address, or an IP address associated with an account

- We require a court order or search warrant for all other kinds of user information, like user access logs or the contents of a private repository

- We will notify affected users about any requests for their account information, unless prohibited from doing so by law or court order

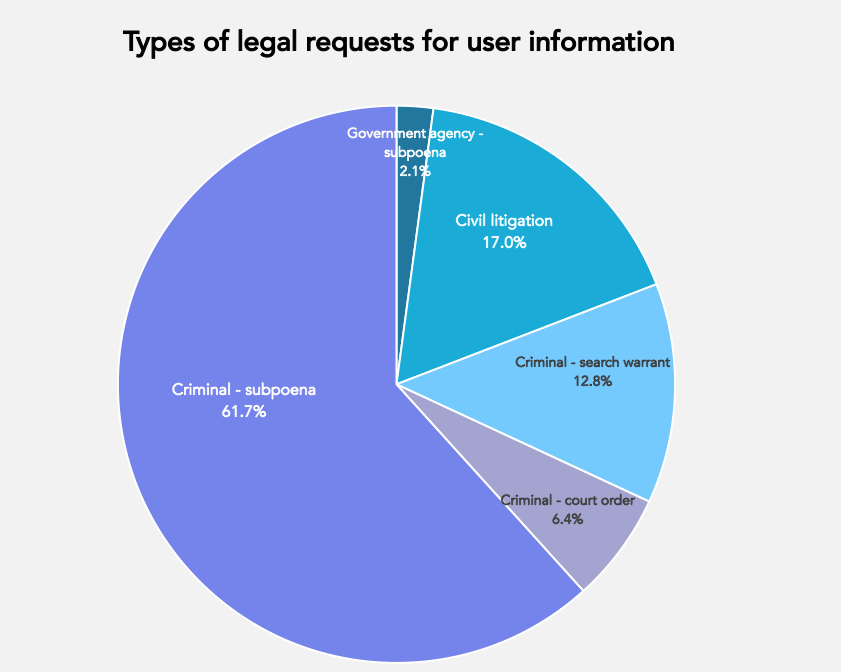

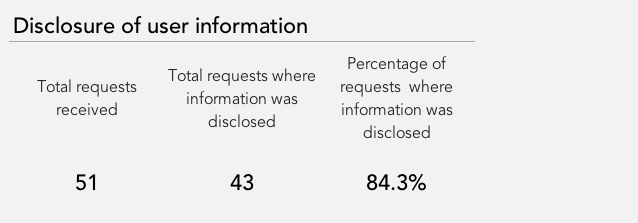

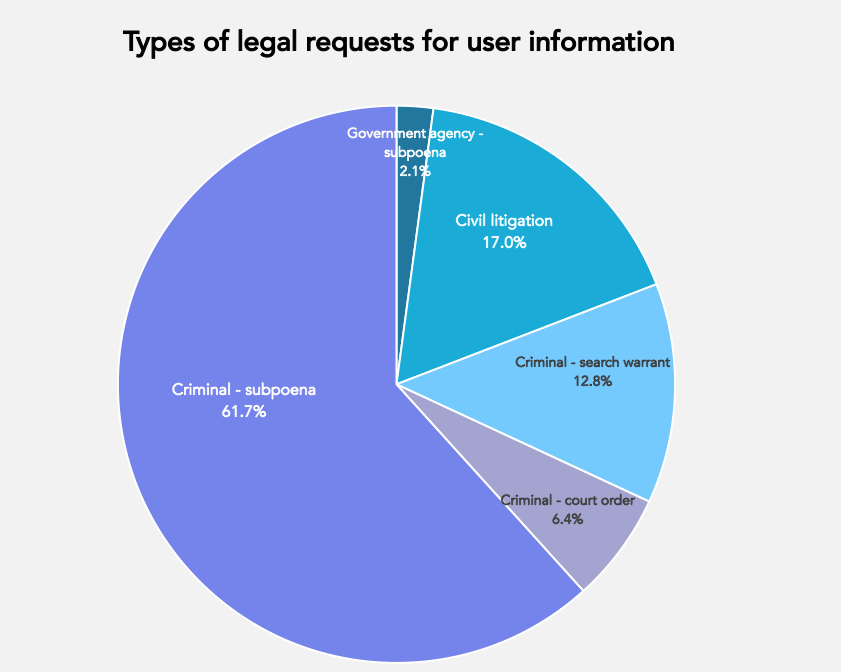

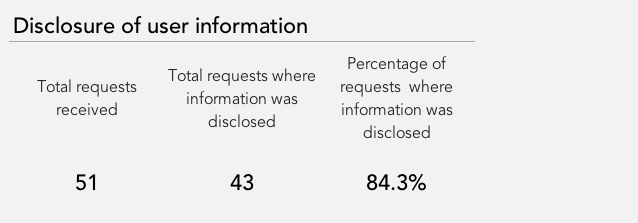

In 2017, GitHub received 51 legal requests to disclose user information, including 42 subpoenas (30 criminal and 12 civil), three court orders, and six search warrants. These include every request we received for user information, regardless of whether we disclosed information or not. Not all of these came from law enforcement; one came from a U.S. government agency, and 12 came from civil litigants requesting information about another party. We also received two cross-border data requests, as described in the next section. Of the 51 requests received, we produced information 43 times.

Governments outside the U.S. can make cross-border data requests for user information through the U.S. Department of Justice via a mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) or similar form of cooperation. Of the 51 requests for legal information described above, GitHub received two requests (one court order and one search warrant) from the U.S. Department of Justice on behalf of non-U.S. government agencies through the MLAT process.

Note legislative developments could lead to increased cross-border data requests and a need for more oversight.

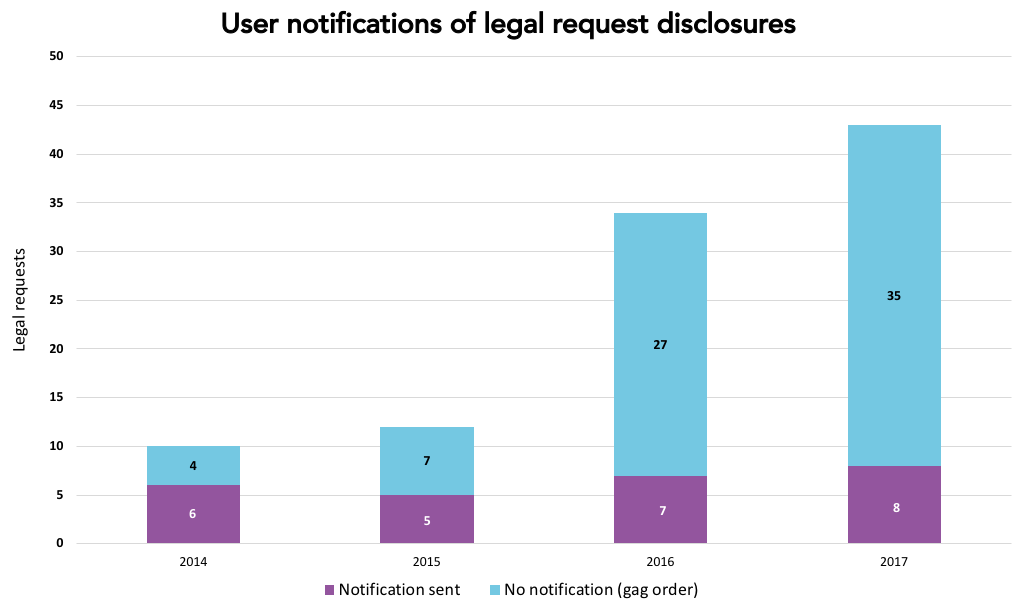

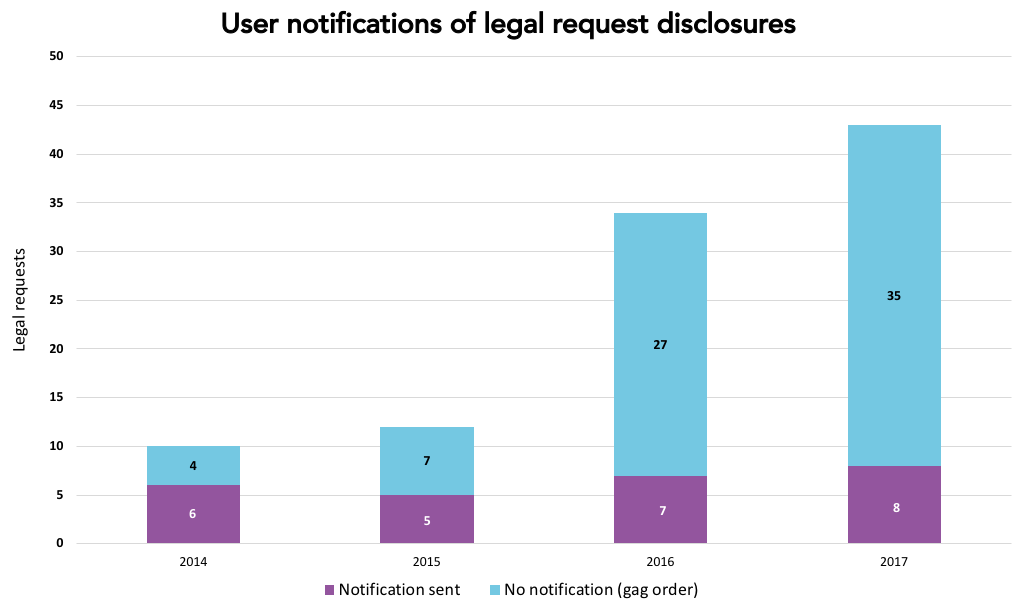

In many cases, legal requests are accompanied by a court order that prevents us from notifying users about the request due to a non-disclosure order, commonly referred to as a gag order. In 2017, of the 43 requests for which we produced information, we did so without being able to notify users 35 times. This represents a considerable increase from last year and continues a rising trend, up from 27 non-disclosure orders in 2016, seven in 2015, and four in 2014.

We did not disclose user information in response to every request we received. In some cases, the request was not specific enough, and the requesting party withdrew the request after we asked for some clarification. In other cases, we received very broad requests, and we were able to limit the scope of the information we provided.

We are very limited in what we can say about national security letters and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) orders. The U.S. Department of Justice has issued guidelines that only allow us to report information about these types of requests in ranges of 250, starting with zero. As the chart below shows, in 2017, we received 0-249 notices in 2017, affecting 0-249 accounts.

Below, we describe two main categories of requests we receive to remove or block user content: government takedown requests and DMCA takedown notices.

From time to time, GitHub receives requests from governments to remove content that they judge to be unlawful in their local jurisdiction (government takedown requests). When we block content at the request of a government, we post the official request that led to the block in a publicly accessible repository. Regarding our process, when we receive a request, we confirm whether:

- The request came from an official government agency

- An official sent an actual notice identifying the content

- An official specified the source of illegality in that country

If we believe the answer is yes to all three, we block the content in the narrowest way we see possible. For instance, we would restrict the removal only to the jurisdictions where the content is illegal. We then post the notice in our government takedowns repository, creating a public record where people can see that a government asked GitHub to take down content.

In 2017, GitHub received eight requests—all from Russia—resulting in eight projects being taken down or blocked (all or part of six repositories, one gist, and one website taken down).

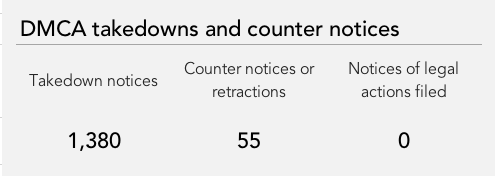

Most content removal requests we receive are submitted under the DMCA, which provides a method by which copyright holders may request GitHub to take down content they believe is infringing. The user who posted the content can then send a counter notice to reinstate content when the alleged infringer states that the takedown was erroneous. Each time we receive a complete DMCA takedown notice, we redact any personal information and post it to a public DMCA repository.

Our DMCA Takedown Policy explains more about the DMCA process, as well as the differences between takedown notices and counter notices. It also sets out the requirements for complete requests, which include that the person submitting the notice take into account fair use.

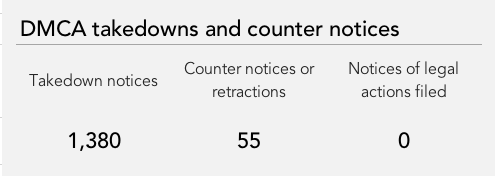

In 2017, GitHub received and processed 1,380 DMCA complete takedown notices and 55 complete counter notices or retractions, for a total of 1,435. In the case of takedown notices, this is the number of separate notices where we took down content or asked our users to remove content.

The notices, counter notices, retractions, and reversals we processed look like this (by month):

From time to time, we receive incomplete or insufficient notices regarding copyright infringement. Because these notices don’t result in us taking down content, we don’t currently keep track of how many incomplete notices we receive, or how often our users are able to work out their issues without sending a takedown notice.

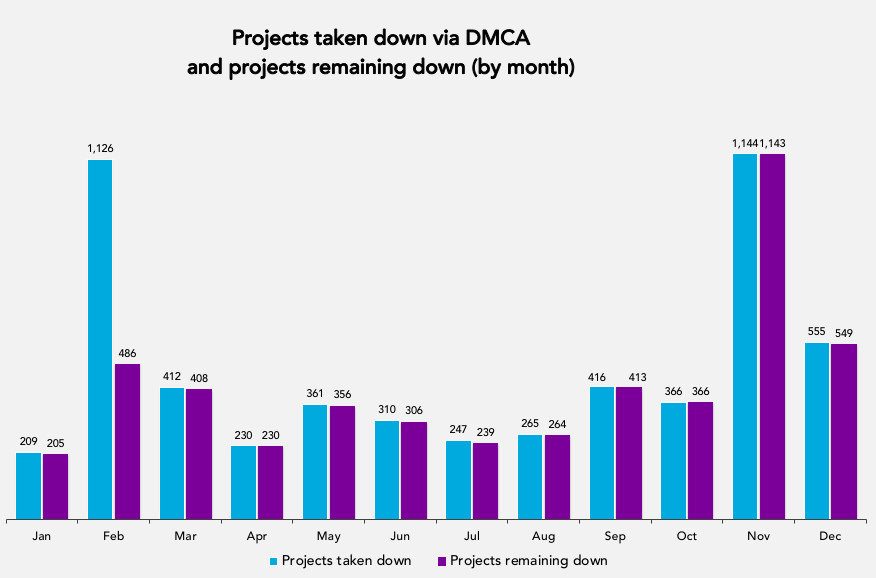

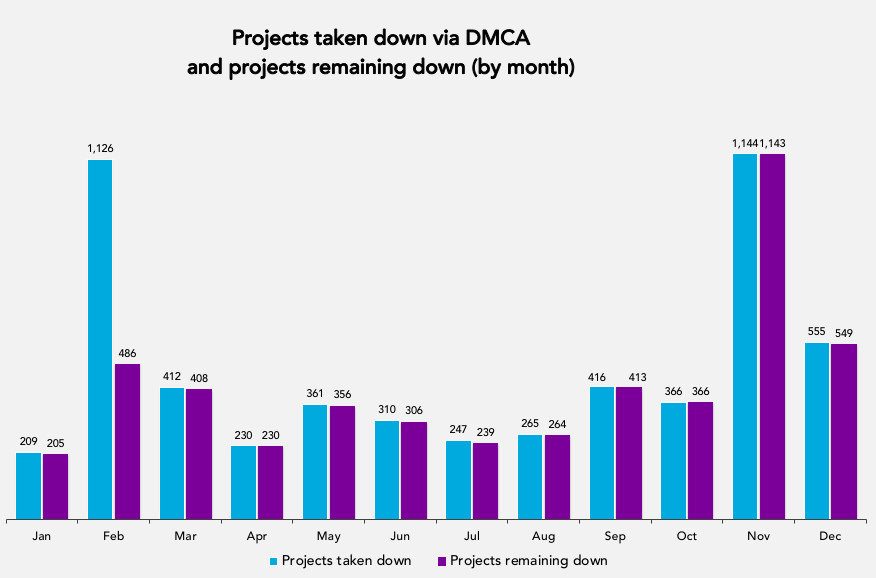

Often, a single takedown notice can encompass more than one project. So, we looked at the total number of projects, such as repositories, gists, and Pages sites, that we had taken down due to DMCA takedown requests in 2017. The projects we took down, and the projects that remained down after we processed retractions and counter notices, looked like this (by month):

Based on DMCA data we’ve compiled over the last few years, we’ve seen an increase in DMCA notices received. This isn’t surprising given that the GitHub community also continues to grow over time. When we overlay the number of DMCA notices with the approximate number of registered users over the same period of time, we can see that the growth in DMCA notices correlates with the growth of the community.

Transparency reports by internet platforms have served to shine a light on censorship and surveillance. The very first of the genre, Google’s 2010 Report, stated “greater transparency will lead to less censorship.” In 2018, platforms are under far greater pressure to censor than they were then, and transparency reports have potential to instead show how willing platforms are to cooperate with censors. More thorough transparency can mitigate this risk—particuarly if platforms, users, advocates, academics, and others interested in free speech, privacy, law enforcement, and more use the data to engage in shared conversations that acknowledge common goals.

As the beginning of this report reflects, GitHub sees transparency reports as necessary, but not sufficient, for good governance. We look forward to continuing to engage in discussions with those stakeholders, including our users, as we strive to promote transparency on our platform.

We hope you enjoyed this year’s report and encourage you to let us know if you have suggestions for additions to future reports.

Written by

I'm GitHub's Director of Platform Policy and Counsel, building and guiding implementation of GitHub’s approach to content moderation. My work focuses on developing GitHub’s policy positions, providing legal support on content policy development and enforcement, and engaging with policymakers to support policy outcomes that empower developers and shape the future of software.