How GitHub uses GitHub to document GitHub

Providing well-written documentation helps people understand, make use of, and contribute back to your project, but it’s only half of the documentation equation. The underlying system used to serve documentation…

Providing well-written documentation helps people understand, make use of, and contribute back to your project, but it’s only half of the documentation equation. The underlying system used to serve documentation can make life easier for the people writing it—whether that’s just you or the team you work with.

The hardest part about documentation should be deciding which words to use, not configuring tools or figuring out how to deploy updates. Members of the GitHub Documentation Team come from backgrounds where crude XML-based authoring tools and complicated CMSs are the norm. We didn’t want to use those tools here so we’ve spent a good deal of time configuring our own documentation workflow and set-up.

We’ve talked before about how we use GitHub to build GitHub; here’s a look at how we use GitHub Pages to serve our GitHub Help documentation to millions of readers each month.

Our previous setup

A few months ago, we migrated our Help site from a custom-built Rails app to a static Jekyll site hosted on GitHub Pages. Our previous Help site consisted of two separate repositories:

- A Rails application, which was responsible for managing the site, the assets, and the search implementation.

- The actual content, which was just a grouping of Markdown files.

Our Rails app was hosted on a third-party service; as updates were made to the code, we deployed them with Hubot and Chatops, as we do with the rest of GitHub.

Our typical writing workflow looked like this:

- The Documentation Team took note when a new feature was shipping.

- We’d create a new issue to track the feature.

- When we were ready, we’d open a pull request to start iterating on the content.

- When the content was in a good place, we’d @mention the team (

@github/docs) and have a peer editor review our words. - When the feature was ready to ship, we’d merge the pull request. A webhook would fire from the content repository to our hosted Rails app; the webhook’s payload updated a database row containing the article’s raw Markdown.

Here’s an example conversation from @neveret and @bernars showing a bit of our normal editing workflow:

Working with pull requests was fantastic, because it directly matched the GitHub flow we use across the company. And we liked writing in Markdown, because its syntax enabled us to effectively describe new features in no time.

However, our Rails implementation was a fairly complicated setup:

- Our reliance on an external host required dedicated employees on our Engineering, Ops, and Security teams to monitor the site and respond to incidents as they arose.

- Our Documentation team couldn’t easily view local changes to the content. Even though we wrote in Markdown, we’d still need to set up a local instance of the Rails app and run a script to import the content into a database, just to see how it would look on the site.

- We were constantly tweaking the Rails server, but noticed that each request a reader made to the site was still slow. The HTML was being generated on-the-fly, requiring calls to the database and constantly iterating on stronger caching strategies.

We knew we could do much better.

Our new setup

When Jekyll 2.0 was released, we saw an opportunity to replace our existing setup with a static site. The new Collections document type lets you define a file structure that matches your needs. In addition, Jekyll 2.0 introduced support for Sass and CoffeeScript assets, which simplifies writing front-end code.

Open source is great because it’s, well, open. As we migrated to Jekyll, we made several pull requests to components of Jekyll, making it a better tool for users of GitHub Pages.

Very little of our original workflow has changed. We still write in Markdown and we still open pull requests for an editorial review. When the pull request is merged, the GitHub Pages site is automatically built and deployed within seconds.

Here’s a quick rundown on how we’re using core Jekyll features and a handful of plugins to implement the help site.

Gems we use

We intentionally rely on core Jekyll code as much as possible, to minimize our reliance on maintaining custom plugins.

Jekyll 2.0 introduced a new plugin type called a Converter that transforms any markup into HTML. This frees the writer up to compose content however she chooses, and Jekyll will just serve the final HTML. For example, you can write your posts in AsciiDoc, if that’s your thing.

To that end, we wrote jekyll-html-pipeline, an implementation of our own open-source html-pipeline. This ensures that the content on our Help site looks the same as content everywhere on GitHub. We also wrote our own Markdown filter to provide some syntax extensions that make writing documentation much easier.

Search

With the previous Rails site, we were using an ElasticSearch provider that indexed our database and implemented a search system for our Help site.

Now, we use lunr-js to provide a faster client-side search experience. In sifting through our analytics, we found that the vast majority of our users relied on an external search provider to get to our documentation. It didn’t make sense, during or after the migration, to expend much energy on a server-side search solution.

Content references

The Docs team really wanted to use “content references,” or conrefs, when writing documentation. A conref allows you to write a chunk of text once and reuse it throughout the site. (The idea was borrowed from the DITA standard.)

The old Rails app wouldn’t permit us to write reusable content, but now we can with the power of Jekyll’s data files. For example, we’ve defined a file called conrefs.yml, and have a set of key-value strings that look something like this:

repositories:

create_new:

1. In the upper-right corner of any page, click {% raw %}{{ octicon-plus Plus symbol }}{% endraw %}, and then click **New repository**.

Our keys are grouped by specificity (repositories.create_new); the values they contain are just plain Markdown (“In the upper-right corner…”). We can now reuse this single step across several pages of content that refer to creating a new repository by writing the appropriate Liquid syntax:

To start the process:

{% raw %}{{ site.data.conrefs.repositories.create_new }}{% endraw %}

2. Do something else.

3. You're done!As GitHub’s UI evolves, we might need to change the image or rewrite the directional pointer. With a conref, we only have to make the change in one location, rather than a dozen.

Versioned documentation

Another goal of the move was to be able to provide versioned Help documentation. With the release of Enterprise 2.0.0, we began to provide different content sets for the previous 11.10.340 and the current 2.0 releases. In order to do that, we build the Jekyll site with a special audience flag, and check in the generated HTML as part of our Pages repository.

For example, in our config.yml file, we set a key called audience to 11.10.340. If a feature exists that’s available in Enterprise 2.0 but not 11.10.340, we demarcate the section using Liquid tags like this:

{% raw %}{% if site.audience != '11.10.340' %}{% endraw %}

This new feature...

{% raw %}{% endif %}{% endraw %}Again, this is just taking advantage of core features in Jekyll; we didn’t need to build or maintain any aspect of this.

Testing our site

Just because the site is static doesn’t mean that we should avoid test-driven development writing.

Our first line of defense for testing content has always been html-proofer. This tool helps verify that none of our links and images are broken by quickly validating every URL in our built site.

Rubyists are familiar with using Capybara to simulate website interactions in their tests. Would it be crazy to implement a similar idea with our static site? Nope! Our own @bkeepers wrote a blog post four years ago talking about this very problem. With that, we were able to write stronger tests that covered our content and our site behavior. For example, we check that a referenced conref is valid (by looking up the key in the YAML file) or that our JavaScript is functioning properly.

Our Help documentation runs with CI to ensure that nothing broken ever gets in front of our readers:

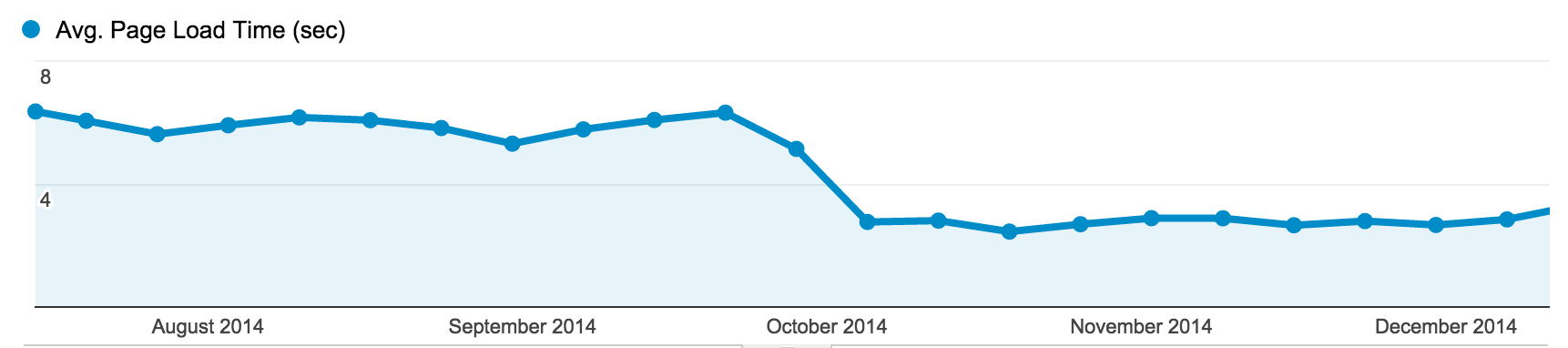

Speed

As mentioned above, our new Pages implementation is significantly faster than the old Rails app. This is partly because the site is a bunch of static HTML files—nothing is fetched from a database. More significantly, we’ve already spent a lot of time configuring our Pages servers to be blazing fast for everyone. The same advantages we have, like serving assets off of a CDN, are also available to every GitHub user.

Making GitHub Pages work for you

Documentation teams across GitHub can take advantage of the GitHub Flow, Jekyll 2.0, and GitHub Pages to produce high-quality documentation. The benefits that GitHub Pages provides to our Documentation team is already available to any user running a GitHub Pages site.

With our move to Pages, we didn’t rebuild any new components. We spent far less time building anything and more time discussing a workflow that made sense for our team and company. By committing to using the same hosting features we provide to every GitHub user, we were able to provide better documentation, faster. Our internal workflow has made us more productive, and enabled us to provide features we never could before, such as versioned content.

If you have any questions on our setup, past or present, we’re happy to help!

Written by

Related posts

Continuous AI for accessibility: How GitHub transforms feedback into inclusion

AI automates triage for accessibility feedback, allowing us to focus on fixing barriers—turning a chaotic backlog into continuous, rapid resolutions.

How we rebuilt the search architecture for high availability in GitHub Enterprise Server

Here’s how we made the search experience better, faster, and more resilient for GHES customers.

From pixels to characters: The engineering behind GitHub Copilot CLI’s animated ASCII banner

Learn how GitHub built an accessible, multi-terminal-safe ASCII animation for the Copilot CLI using custom tooling, ANSI color roles, and advanced terminal engineering.