Direct instruction marking in Ruby 2.6

We recently upgraded GitHub to use the latest version of Ruby 2.6. Ruby 2.6 contains an optimization for reducing memory usage.

We recently upgraded GitHub to use the latest version of Ruby 2.6. Ruby 2.6 contains an optimization for reducing memory usage. We’ve found it to reduce the “post-boot live heap” by about 3 percent. The “post-boot live heap” are the objects still referenced and not garbage collected after booting our Rails application, but before accepting any requests.

Ruby’s virtual machine

MRI (Matz’s Ruby Implementation) uses a stack-based virtual machine. Each instruction manipulates a stack, and that stack can be thought of as a sort of a “scratch space”. For example, the program 3 + 5 could be represented with the instruction sequences:

push 3

push 5

addAs the virtual machine executes, each instruction manipulates the stack:

Abstract Syntax Trees in Ruby

Before the virtual machine has something to execute, the code must go through a few different processing phases. The code is tokenized, parsed, turned in to an AST (or Abstract Syntax Tree), and finally the AST is converted to byte code. The byte code is what the virtual machine will eventually execute.

Let’s look at an example Ruby program:

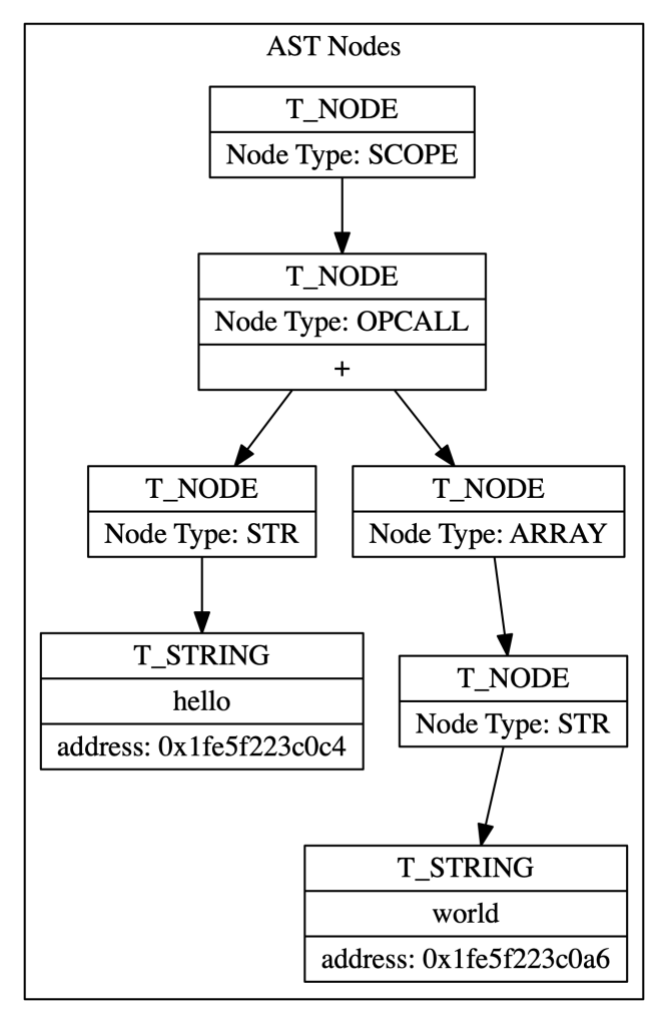

"hello" + "world"This code is turned into an AST, which is a tree data structure. Each node in the tree is represented internally by an object called a T_NODE object. The tree for this code will look like this:

Some of the T_NODE objects reference literals. In this case some T_NODE objects reference the string literals “hello” and “world”. Those string literals are allocated via Ruby’s Garbage Collector. They are just like any other string in Ruby, except that they happen to be allocated as the code is being parsed.

Translating the AST to instructions

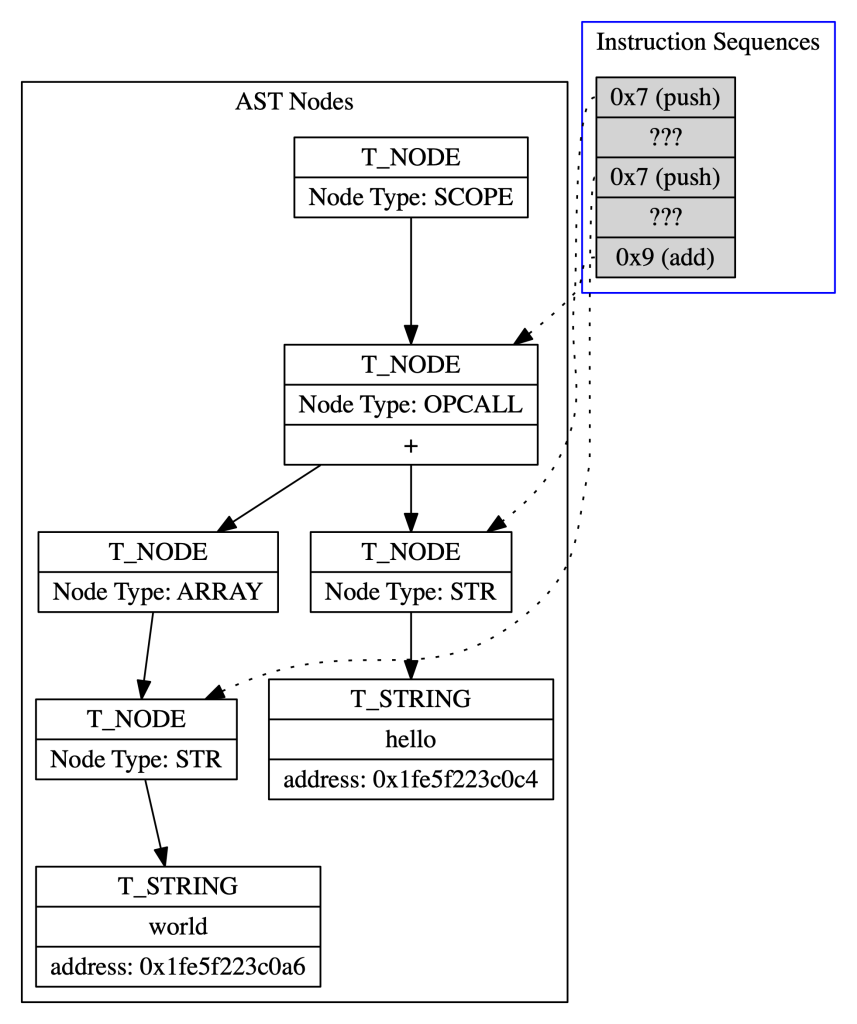

Instructions and their operands are represented as integers and can only be represented as integers. Instruction sequences for a program are just a list of integers, and it’s up to the virtual machine to interpret the meaning of those integers.

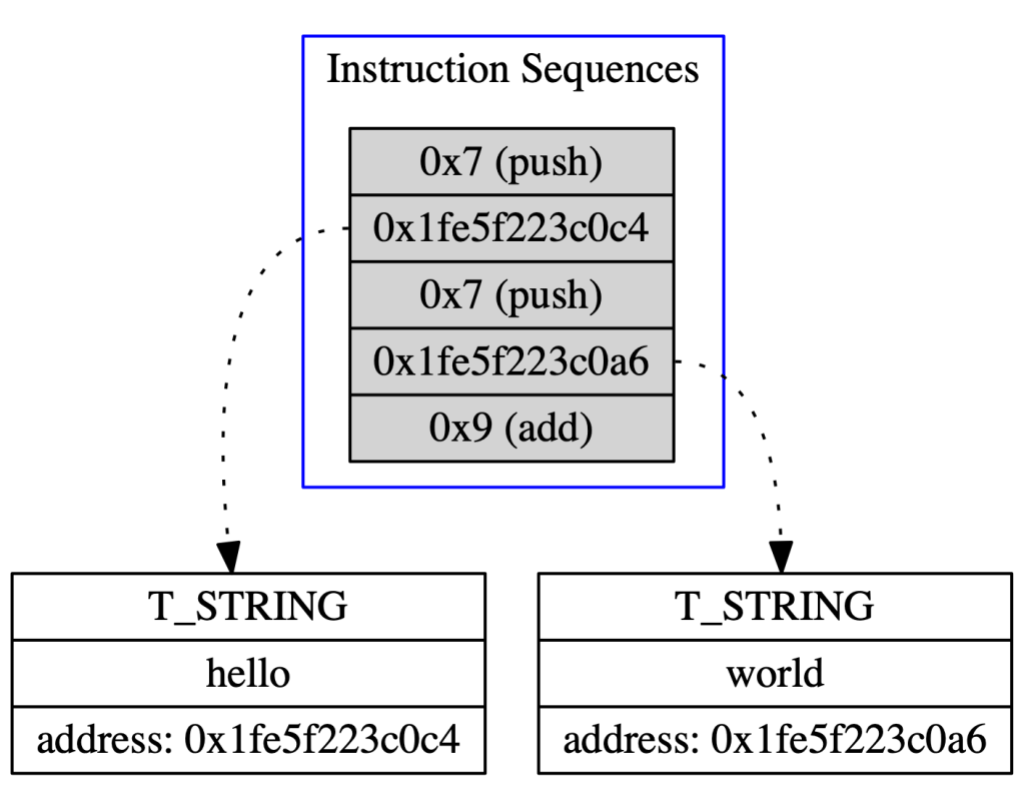

The compilation process produces the list of integers that the virtual machine will interpret. To compile a program, we simply walk the tree translating nodes and their operands to integers. The program "hello" + "world" will result in three instructions: two push operations and one add operation. The push instructions have "hello" and "world" as operands.

There are a fixed number of instructions, and we can represent each instruction with an integer. In this case, let’s use the number 7 for push and the number 9 for add. But how can we convert the strings “hello” and “world” to integers?

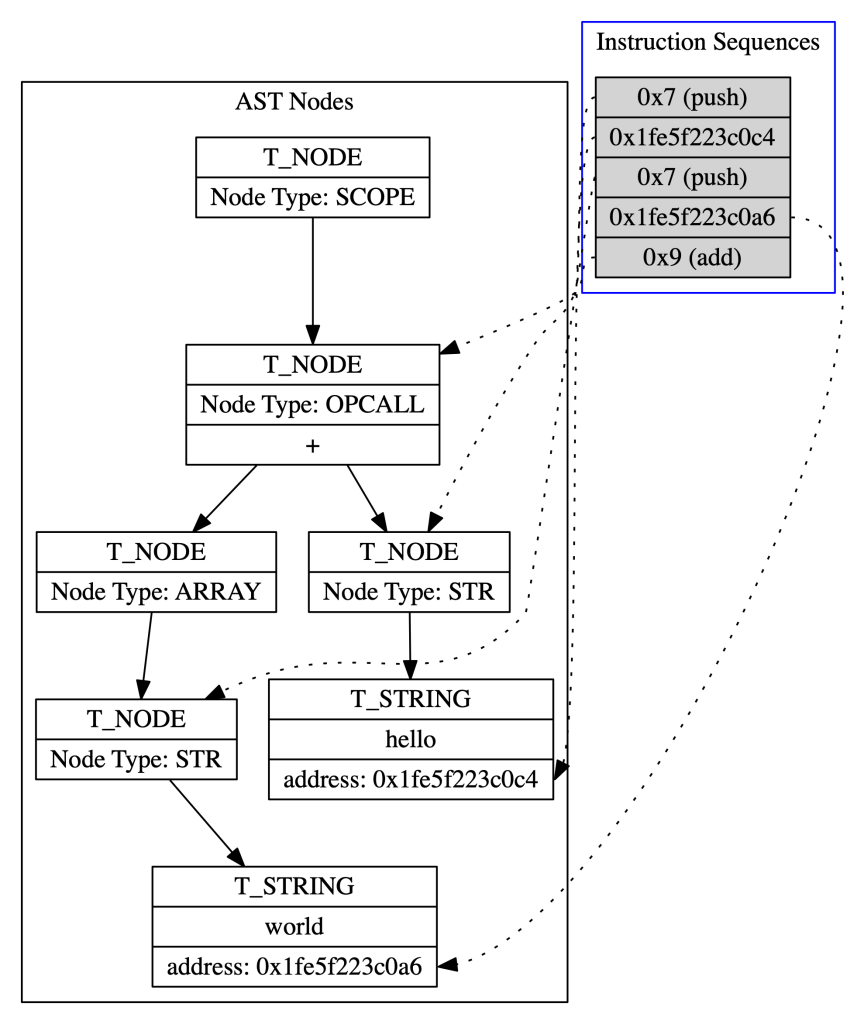

In order to represent these strings in the instruction sequences, the compiler will add the address of the Ruby object that represents each string. The virtual machine knows that the operand to the push instruction is actually the address of a Ruby object, and will act appropriately. This means that the final instructions will look like this:

After the AST is fully processed, it is thrown away and only the instruction sequences remain:

Literal liveness in Ruby 2.5

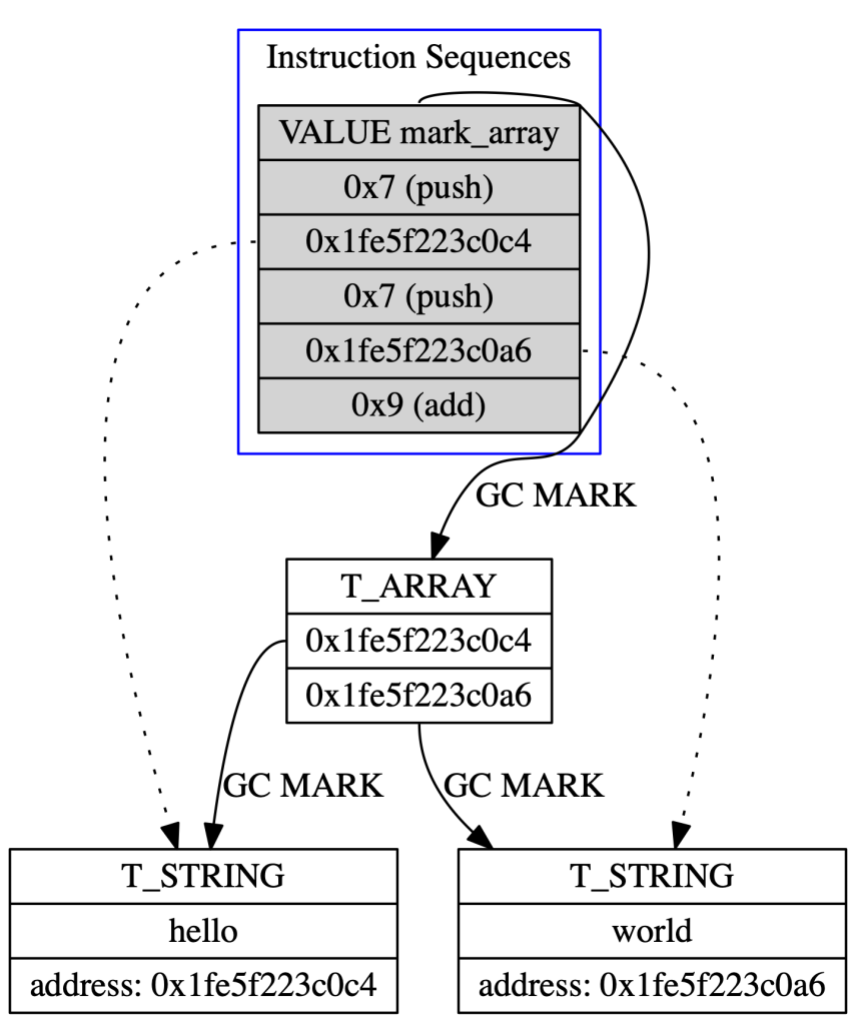

Instruction Sequences are Ruby objects and are managed via Ruby’s garbage collector. As mentioned earlier, string literals are also Ruby objects and are managed by the garbage collector. If the string literals are not marked, they could be collected, and the instruction sequences would point to an invalid address.

To prevent these literal objects from being collected, Ruby 2.5 would maintain a “mark array”. The mark array is simply a Ruby array that contains references to all literals referenced for that set of instruction sequences:

Both the mark array and the instructions contain references to the string literals found in the code. But the instruction sequences depend on the mark array to keep the literals from being collected.

Literal liveness in Ruby 2.6+

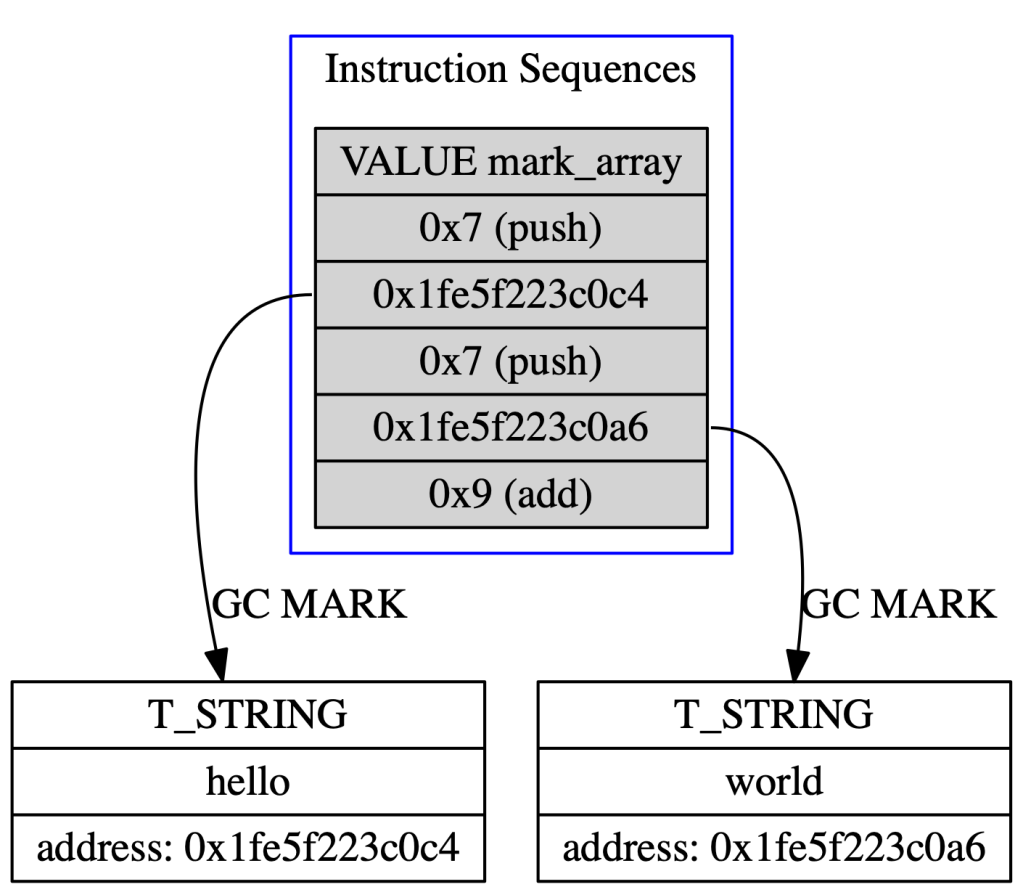

Ruby 2.6 introduced a patch that eliminates this mark array. When instruction sequences are marked, rather than marking an array, it disassembles the instructions and marks instruction operands that were allocated via the garbage collector. This disassembly process means that the mark array can be completely eliminated:

We found that this reduced the number of live objects in our heap by three percent after the application starts.

Performance

Of course, disassembling instructions is more expensive than iterating an array. We found that only 30 percent of instruction sequences actually contain references to objects that need marking. In order to prevent needless disassembly, instructions that contain objects allocated from Ruby’s garbage collector are flagged at compile time, and only those instruction sequences are disassembled during mark time. On top of this, instruction sequence objects typically become “old”. This means that thanks to Ruby’s generational garbage collector, they are examined very infrequently. As a result, we observed memory reduction with zero cost to throughput.

Have a good day!

Written by

Related posts

How GitHub engineers tackle platform problems

Our best practices for quickly identifying, resolving, and preventing issues at scale.

GitHub Issues search now supports nested queries and boolean operators: Here’s how we (re)built it

Plus, considerations in updating one of GitHub’s oldest and most heavily used features.

Design system annotations, part 2: Advanced methods of annotating components

How to build custom annotations for your design system components or use Figma’s Code Connect to help capture important accessibility details before development.