February 20, 2020—This post was updated to reflect final numbers for 2018 that were processed after the initial publication.

At GitHub, we believe that maintaining transparency is an essential part of our commitment to our users. For the past four years (2017, 2016, 2015, 2014), we’ve published transparency reports to better inform the public about GitHub’s disclosure of user information and removal of content.

Since we released our first transparency report, the landscape has changed. Back then, companies’ transparency reports tended to focus on when companies handed over user information to governments.

We now see a growing interest in content moderation, or when and why companies remove information from their platforms. Content moderation can raise free expression concerns regardless of whether it starts with a government or with a user. Being transparent about content removal policies and restricting content removal as narrowly as possible are among the United Nations free speech expert’s recommendations to platforms for promoting free expression in content moderation online. At GitHub, we do both.

More specifically, we promote transparency by:

- Directly engaging our users in developing our policies

- Explaining our reasons for making policy decisions

- Notifying users when we need to restrict content, with our reasons

- Allowing users to appeal removal of their content

- Publicly posting takedown requests (requests to remove content) in real time in a public repository

Check out our contribution to the UN expert’s report for more details.

In this report, we’ll review 2018 stats for:

- Requests to disclose user information

- Subpoenas

- Court orders

- Search warrants

- National security letters and orders

- Cross-border data requests

- Requests to remove or block user content

- Government takedown requests

- Takedown notices for alleged copyright infringement under the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

We also added a new data point this year: accounts affected by legal requests for user information.

And before you dive in—if you’re unfamiliar with any of the GitHub terminology we use in this report, refer to the GitHub Glossary.

GitHub’s Guidelines for Legal Requests of User Data explain how we handle legally authorized requests, including law enforcement requests, subpoenas, court orders, search warrants, and national security letters and orders.

Legally authorized requests of user data don’t always require review by a judge or a magistrate. Subpoenas (written orders to compel someone to testify on a particular subject) and national security letters don’t require judicial review and are limited in what they can be used to obtain. So while a national security letter is similar to a subpoena, it can only be used for matters of national security.

By contrast, search warrants and court orders both require judicial review. A national security order is a type of court order that can be put in place, for example, to produce information or authorize surveillance. National security orders are issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a specialized U.S. court for national security matters.

As we note in our guidelines:

- We only release information to third parties when the appropriate legal requirements have been satisfied, or where we believe it’s necessary to prevent an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to a person.

- We require a subpoena to disclose certain kinds of user information, like a name, an email address, or an IP address associated with an account, unless we determine disclosure (as limited as possible) is necessary to prevent an emergency involving danger of death or serious physical injury to a person.

- We require a court order or search warrant for all other kinds of user information, like user access logs or the contents of a private repository.

- We will notify affected users about any requests for their account information unless prohibited from doing so by law or court order.

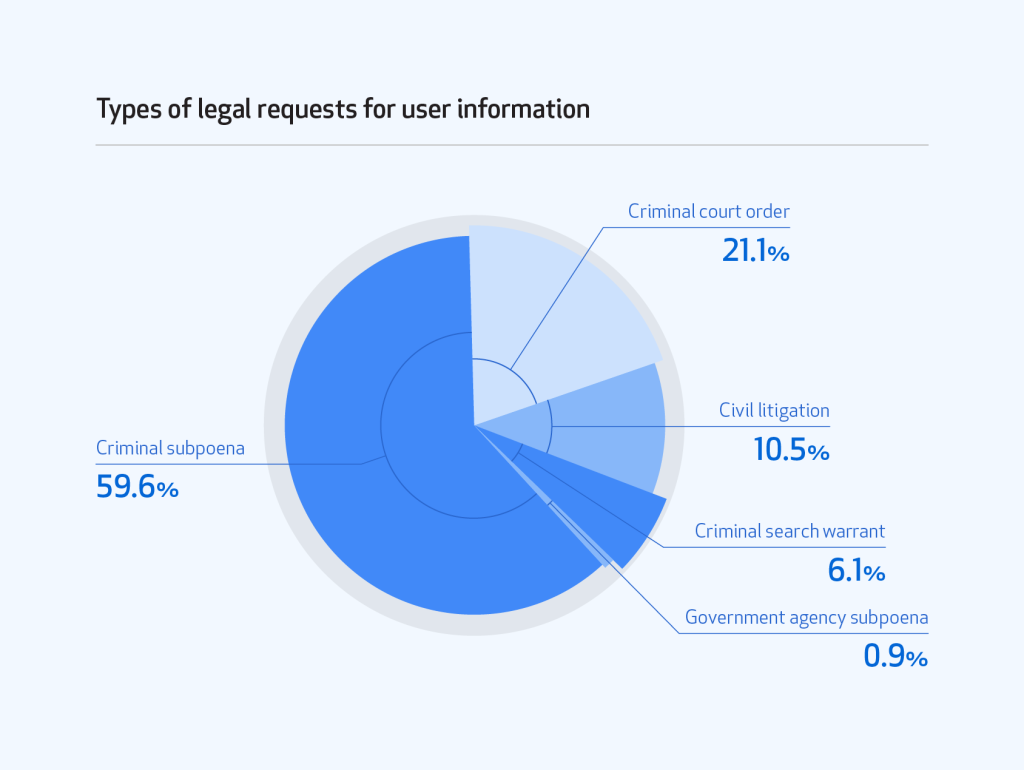

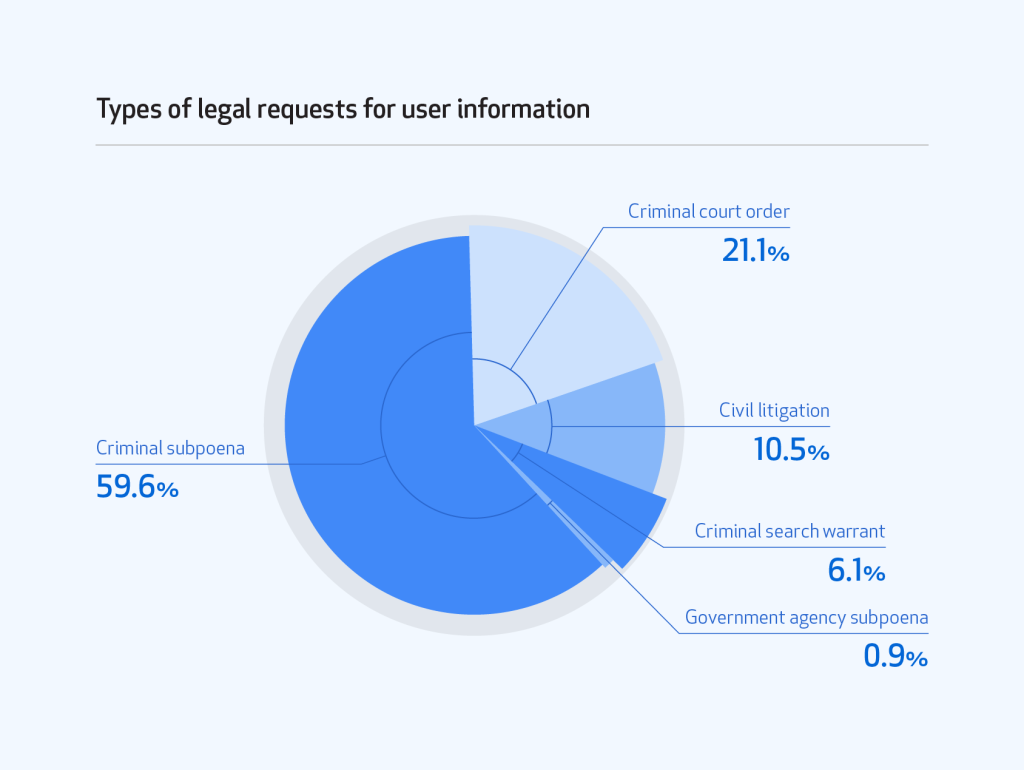

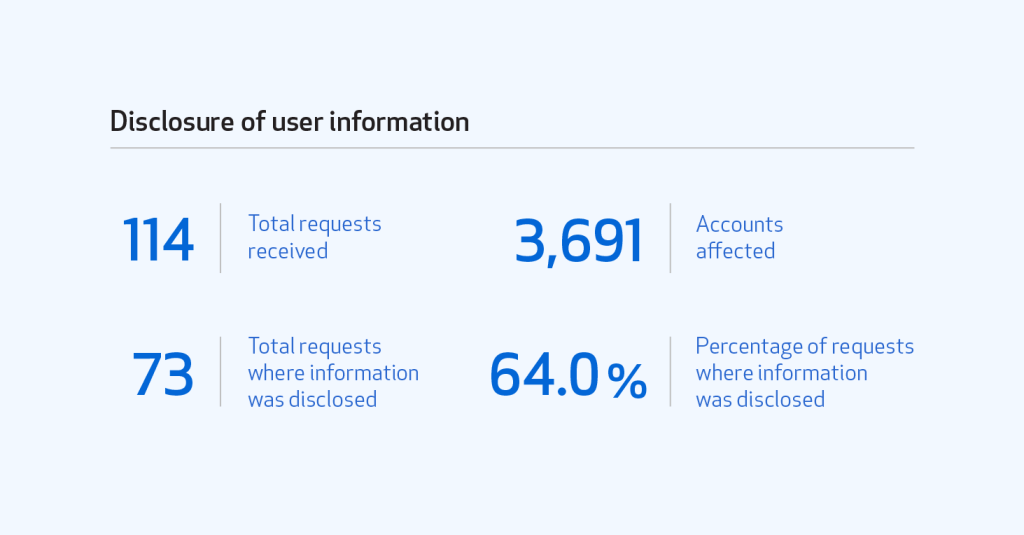

In 2018, GitHub received 114 requests to disclose user information—more than twice as many as we did in 2017. Of those 114 requests, we received 81 subpoenas (68 criminal and 13 civil), 24 court orders, and seven search warrants. That also includes two cross-border data requests, which we’ll share more about later in this report. These numbers represent every request we received for user information, regardless of whether we disclosed information or not. See the next sections on disclosure and notification for more information.

Not every request came from law enforcement; of the 13 civil subpoenas, one came from a U.S. government agency and 12 came from civil litigants wanting information about another party.

Disclosure and notification

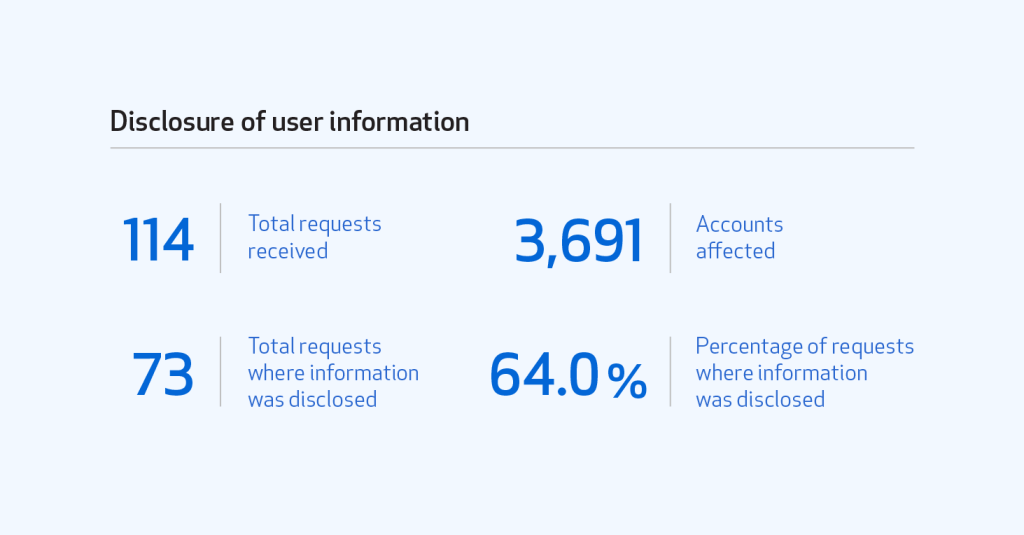

We didn’t disclose user information in response to every request we received. In some cases, the request was not specific enough and the requesting party withdrew the request after we asked for clarification. In other cases, we received very broad requests and we were able to limit the scope of the information we provided. Due to the nature of legal requests, they can also take some time to process. Of the requests we received in 2018, we disclosed information 73 times. Those disclosures affected 3,691 accounts—but not always proportionally. In 2018, two requests alone affected 3,582 accounts. The other 71 requests affected a total of 109 accounts.

Requests that affect a large number of users typically occur when a court order seeks information about access to a piece of content posted on GitHub, rather than targeting specific users. In these cases, GitHub will share log data—including usernames and IP addresses—in connection with access to the content at a specific window of time. But GitHub does not typically share further private information, like email addresses, about every user that accessed the content without receiving a specific request.

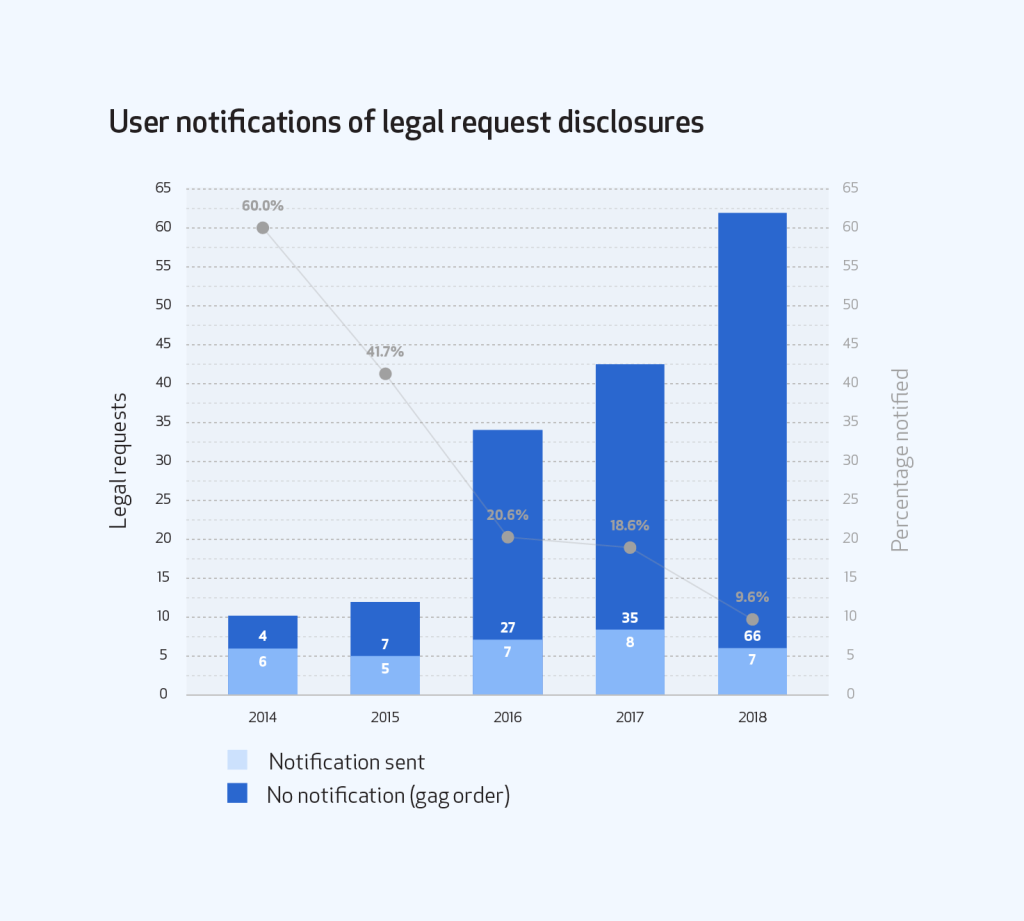

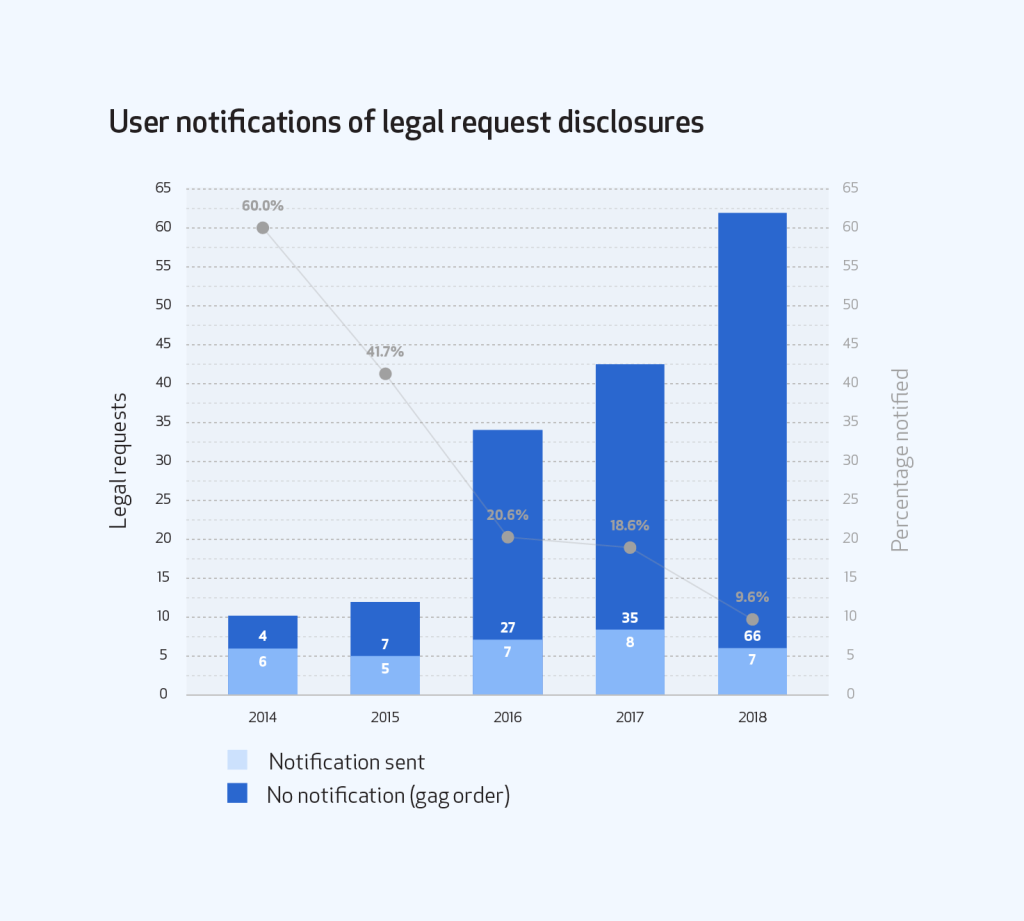

We notify users when we disclose their information in response to a legal request unless a law or court order prevents us from doing so. In many cases, legal requests are accompanied by a court order that prevents us from notifying users due to a non-disclosure order, commonly referred to as a gag order. In 2018, we received 102 gag orders. This continues to be a rising trend as a percentage of overall requests.

It’s probably not surprising that we’re receiving more user information requests as the GitHub community grows. But what does stand out is how often those information requests are accompanied by gag orders. That’s not something that we’d expect to increase faster than the number of requests we receive.

To put this in perspective, of the 73 times we produced information in 2018, we were only able to notify users seven times because gag orders accompanied the other 66 requests. That means we were only permitted to notify users about information disclosure 9.6 percent of the time in 2018, compared to 18.6 percent in 2017, 20.6 percent in 2016, 41.7 percent in 2015, and 60 percent in 2014.

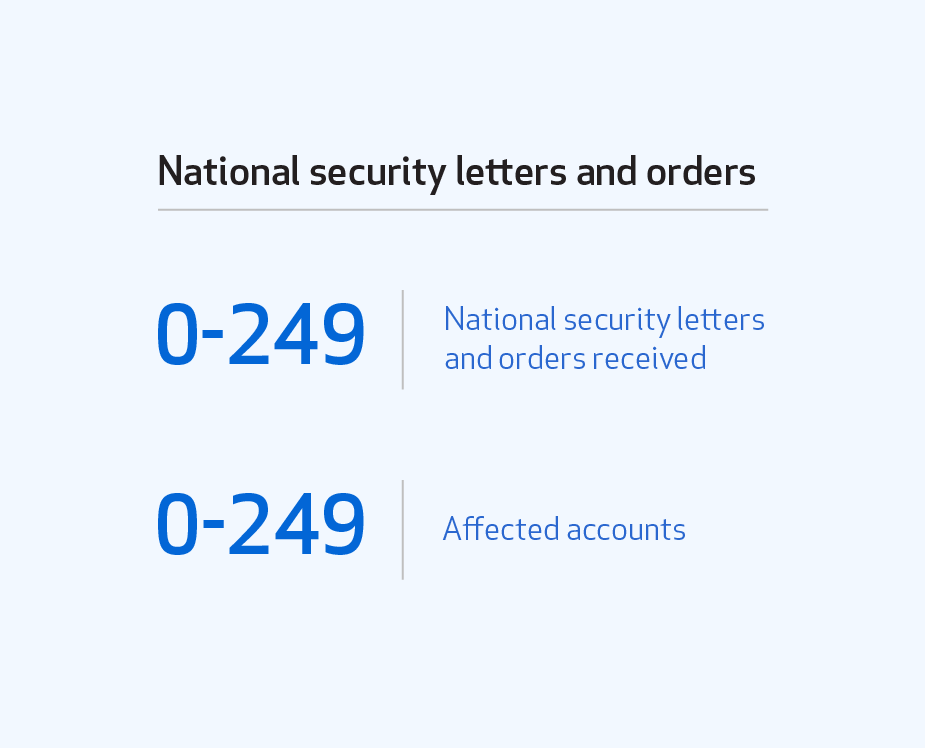

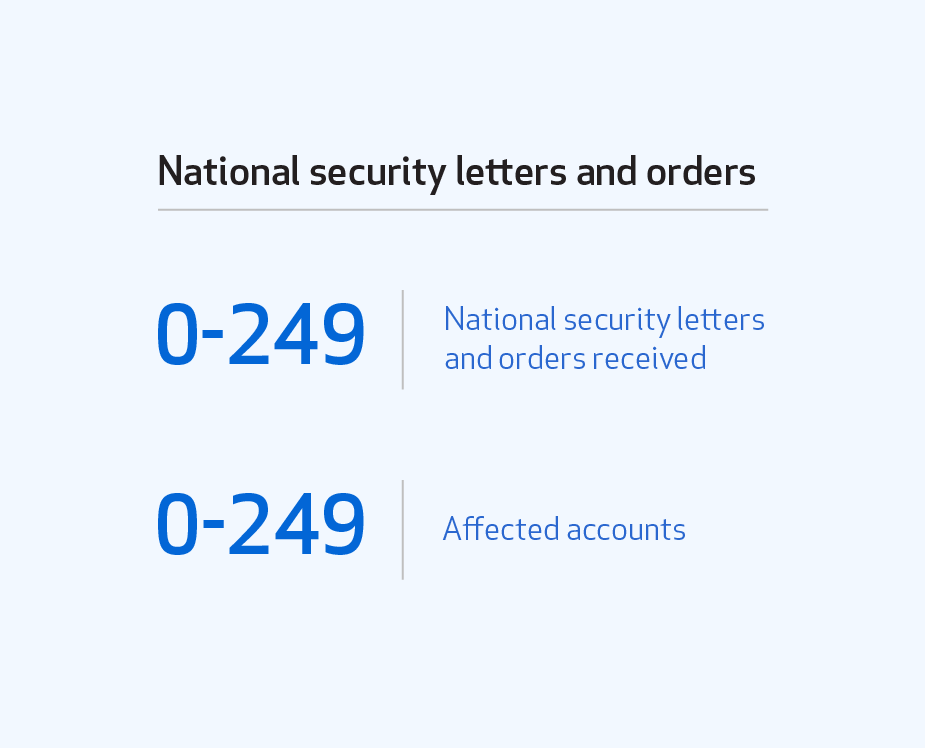

We are very limited in what we can say about national security letters and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) orders. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has issued guidelines that only allow us to report information about these types of requests in ranges of 250, starting with zero. As shown below, we received 0–249 notices in 2018, affecting 0–249 accounts.

Governments outside the U.S. can make cross-border data requests for user information through the DOJ via a mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) or similar form of international legal process. Under the MLAT process, when a foreign government seeks user information from GitHub, we direct the government to the DOJ so that the DOJ can determine whether the request complies with U.S. legal protections.

If it does, the DOJ would send us a subpoena, court order, or search warrant, which we would then process like any other requests we receive from the U.S. government. When we receive these requests from the DOJ, they don’t necessarily come with enough context for us to know whether they’re originating from another country. Our statistics for subpoenas, court orders, and search warrants include any DOJ requests that originated from another country.

Sometimes, another country will contact us directly for user information, in which case our practice is to refer them to the DOJ to use the MLAT process. In 2018, we received two requests directly from foreign governments. One government withdrew its request. The other contacted us due to exigent circumstances related to imminent bodily harm and we produced limited information in response.

We’ve updated our Guidelines for Legal Requests of User Data to clarify our disclosure and notification practices under such circumstances.

Ongoing developments could lead to increased cross-border data requests and a need for more oversight.

Below, we describe two main categories of requests we receive to remove or block user content: government takedown requests and DMCA takedown notices.

From time to time, GitHub receives requests from governments to remove content that they judge to be unlawful in their local jurisdiction (government takedown requests). When we block content at the request of a government, we post the official request that led to the block in our public government takedowns repository. When we receive a request, we confirm whether:

- The request came from an official government agency

- An official sent an actual notice identifying the content

- An official specified the source of illegality in that country

If we believe the answer is “yes” to all three, we block the content in the narrowest way we see possible. For instance, we would block content only in the jurisdictions where the content is illegal—not everywhere. We then post the notice in our government takedowns repository, creating a public record where people can see that a government asked GitHub to take down content.

In 2018, GitHub received nine requests—all from Russia—resulting in nine projects (all or part of three repositories, five gists, and one GitHub Pages site) being blocked in Russia. GitHub received zero requests from governments to take down content as a Terms of Service violation.

Most content removal requests we receive are submitted under the DMCA, which allows copyright holders to ask GitHub to take down content they believe infringes on their copyright. The user who posted the “infringing” content can then send a counter notice asking GitHub to reinstate the content if they believe the takedown was a mistake or misidentification. Each time we receive a complete DMCA takedown notice, we redact any personal information and post that notice to a public DMCA repository.

Our DMCA Takedown Policy explains more about the DMCA process, as well as the differences between takedown notices and counter notices. It also sets out the requirements for making a complete request, which include that the person submitting the notice take into account fair use.

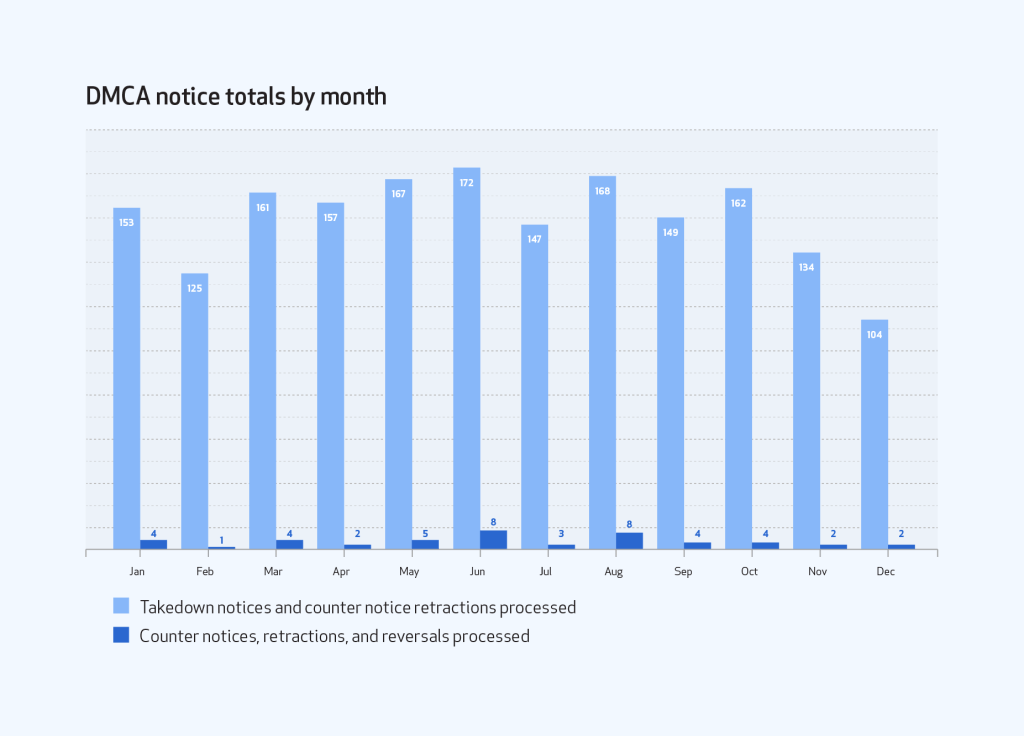

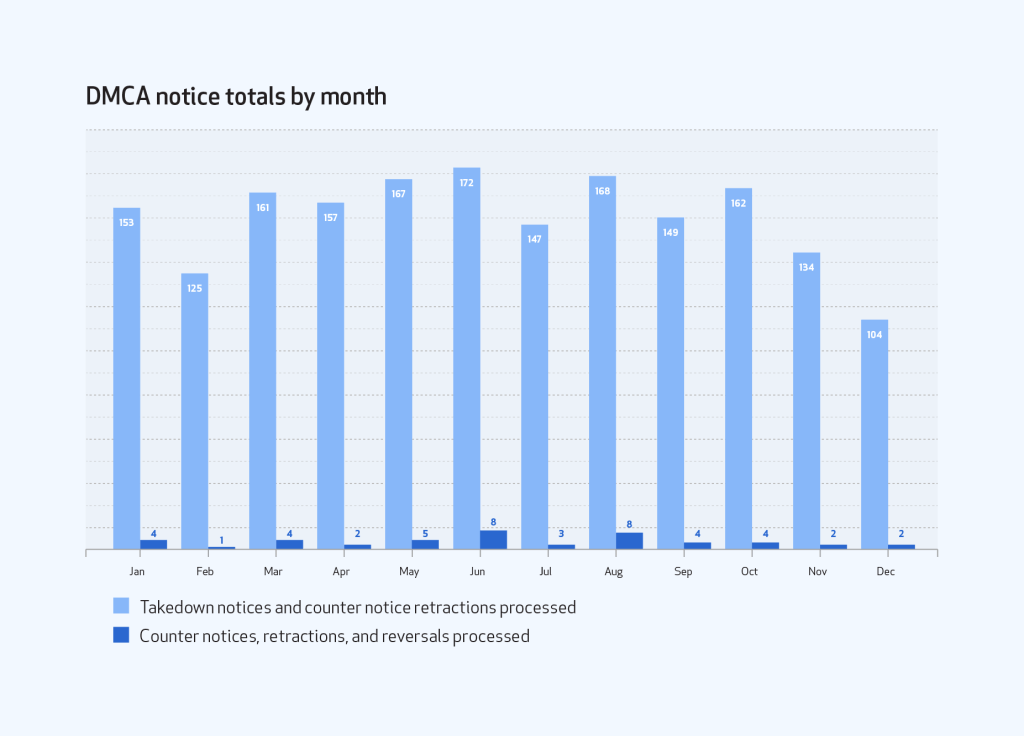

In 2018, GitHub received and processed 1,799 DMCA complete takedown notices and 47 complete counter notices or retractions, plus three complete counter notice retractions (that’s not a typo—read on to learn more), for a total of 1,849 notices. In the case of takedown notices, this is the number of separate notices where we took down content or asked our users to remove content. We also received one notice of legal action filed related to a DMCA takedown request.

While content can be taken down, it can also be restored. In some cases we will reinstate content that was taken down if we receive a:

- Counter notice: the person whose content was removed sends us sufficient information to allege that the takedown was the result of a mistake or misidentification

- Retraction: the person who filed the takedown changes their mind and requests to withdraw it

- Reversal: after receiving a seemingly complete takedown request, GitHub later receives information that invalidates it and we reverse our original decision to honor the takedown notice

In 2018, we had a new addition: counter notice retraction. This occurred when people who had sent us counter notices withdrew them shortly after sending them to us. As a result, content that was taken down remained down. In case the terminology is getting confusing, we use “retraction” to mean retraction of a takedown notice and “counter notice retraction” to mean retraction of a counter notice. So in both cases, someone is retracting (taking back) their notice, but the difference is what they’re retracting (a takedown notice versus a counter notice).

The takedown notices, counter notices, retractions, reversals, and counter notice retractions we processed look like this:

For most months, the totals ranged from 125 to 172 takedown notices. The exception was December when we received only 104. The monthly totals for counter notices and retractions (together) ranged from one to eight, correlating more or less with the volume of takedown notices those months.

All of those numbers were about complete notices we received. We also received a lot of incomplete or insufficient notices regarding copyright infringement. Because these notices don’t result in us taking down content, we don’t currently keep track of how many incomplete notices we receive, or how often our users are able to work out their issues without sending a takedown notice.

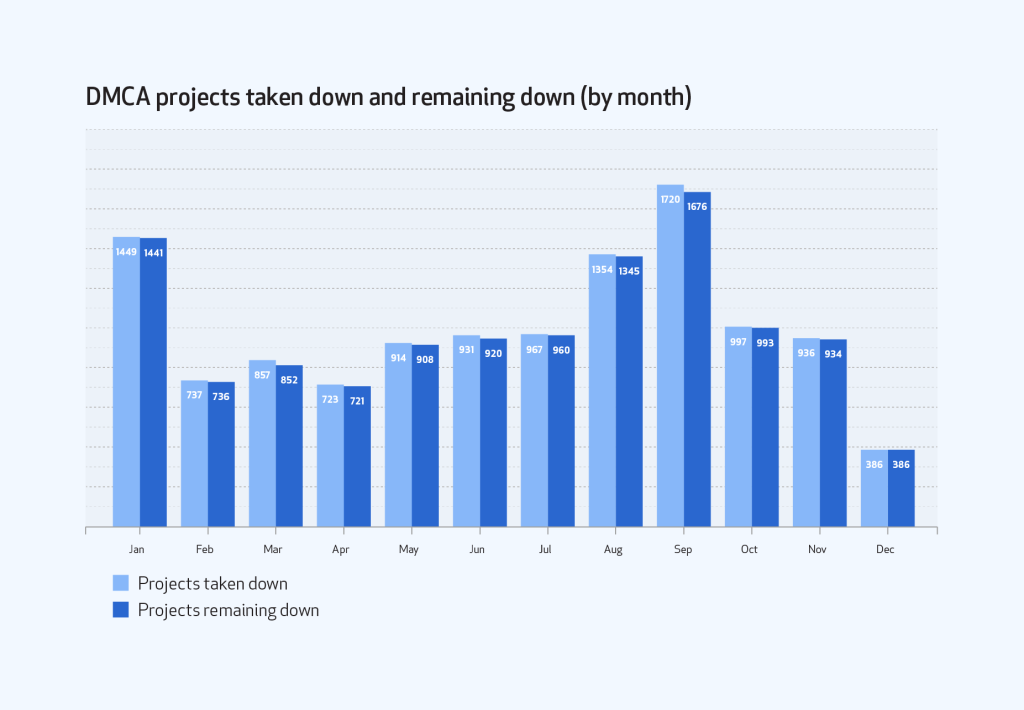

Often, a single takedown notice can encompass more than one project. So we looked at the total number of projects, including repositories, gists, and GitHub Pages sites, that we had taken down due to DMCA takedown requests in 2018.

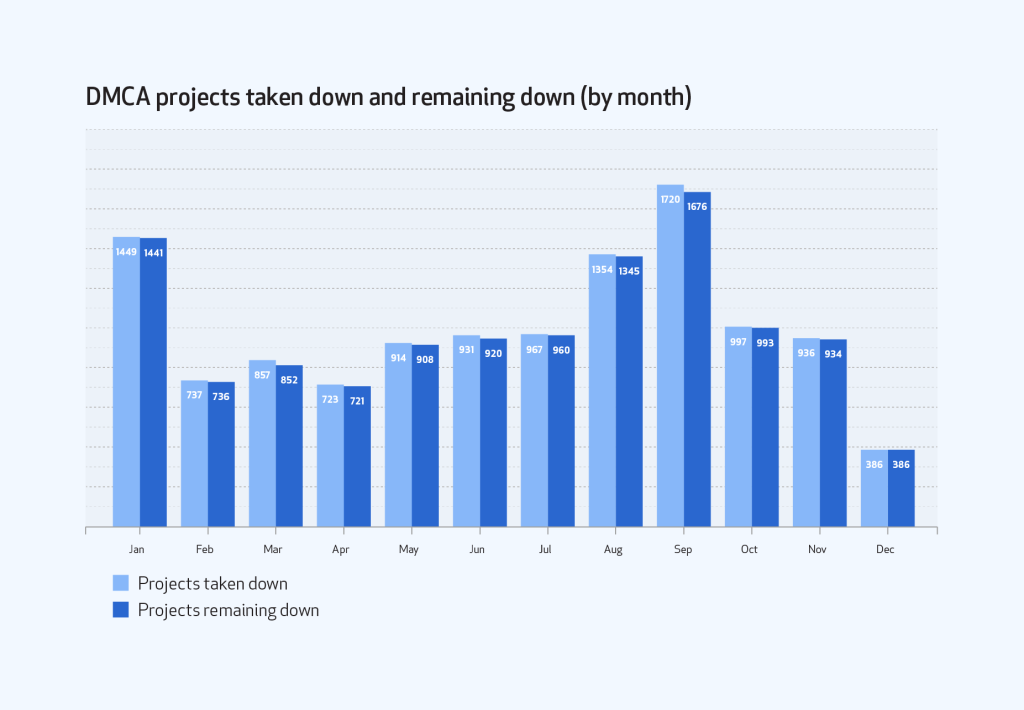

The projects we took down, and the projects that remained down after we processed retractions and counter notices, looked like this:

In most months, less than 10 projects were reinstated. The exception this year was September, when we reinstated 44 projects, though that only amounted to 2.5 percent of projects affected by takedown notices that month. That’s typical—the number of counter notices and retractions we receive amounts to only 2 to 4 percent of the DMCA-related notices we get each month. This means that most of the time when we receive a complete takedown notice, the content comes down and stays down. In total in 2018, we took down 11,971 projects and reinstated 99, so 11,872 projects stayed down.

11,872 may sound like a lot of projects, but it’s only about one one-hundredth of a percent (0.012 percent) of the more than 100 million repositories on GitHub at the end of 2018.

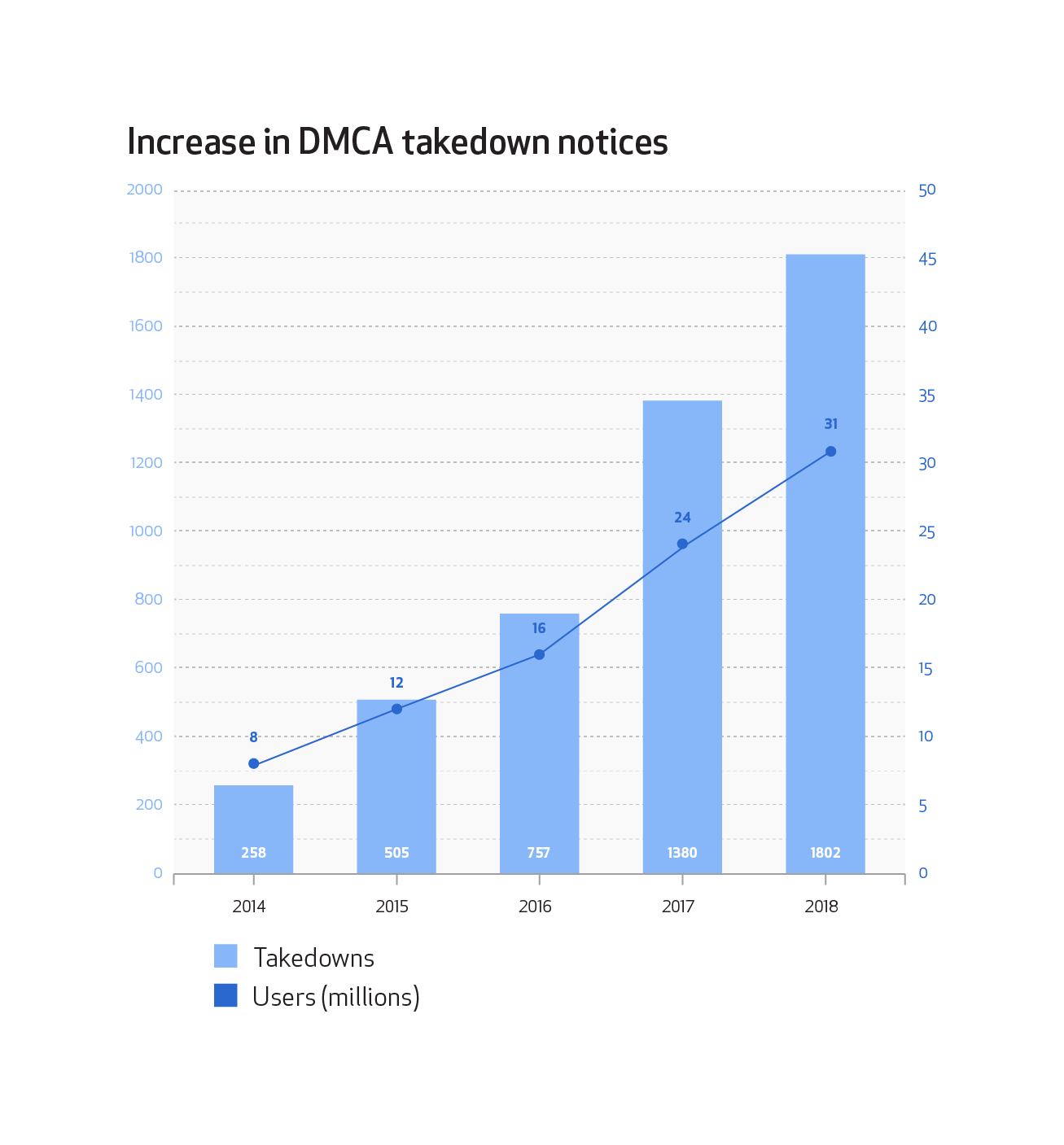

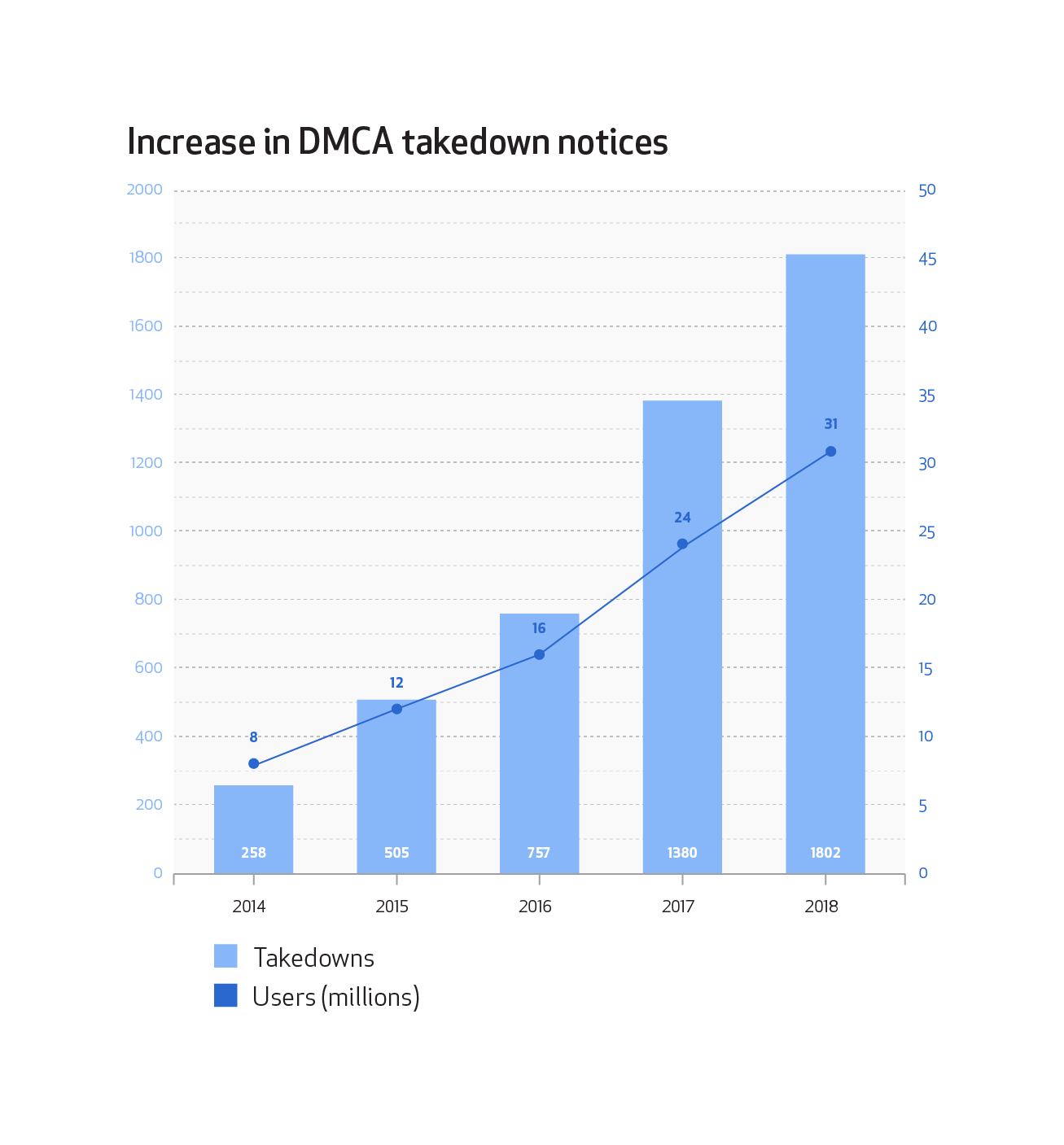

Based on DMCA data we’ve compiled over the last few years, we’ve seen an increase in DMCA notices received. Just like with gag order requests, this isn’t surprising given that the GitHub community also continues to grow over time. When we compare the number of DMCA notices with the approximate number of registered users over the same period of time, we can see that the growth in DMCA notices correlates with the growth of the community.

Like we shared at the beginning, transparency reporting has broadened as people pay more attention to companies’ practices on information disclosure and removal. One recent example is the Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability of Content Moderation Practices. We support the spirit of those principles and are working to align our practices with them with as much as possible. Through our transparency reports, we’re continuing to shed light on our own practices, while also hoping to contribute to broader discourse on platform governance.

We hope you found this year’s report to be helpful and encourage you to let us know if you have suggestions for additions to future reports. For more on how we develop GitHub’s policies and procedures, check out our site policy repository.

Written by

I'm GitHub's Director of Platform Policy and Counsel, building and guiding implementation of GitHub’s approach to content moderation. My work focuses on developing GitHub’s policy positions, providing legal support on content policy development and enforcement, and engaging with policymakers to support policy outcomes that empower developers and shape the future of software.